The title of this article is inspired from the novel Love in the Time of Cholera by the Colombian Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez.

The year 1817 saw the beginning of the end of independent Indian rule in the country as the British and Marathas engaged themselves in one last war. It was also the year in which that morbus horribilis – cholera – broke out in Bengal before spreading across India and Asia and triggering, what was later called, the ‘First Cholera Pandemic’.1

The first two sections of this deals with medical and political history of the time. The third looks at a Lieutenant’s letter from his camp, mainly for its contents, but also its postal history.

The ‘Blue Death’

Cholera is an infectious disease caused by a waterborne bacterium called Vibrio cholerae. People contract the disease after consuming contaminated liquids or foods. The bacteria colonise the intestines and release toxins, which cause severe diarrhea and vomiting. Dehydration (leading to a bluish-grey skin tone), septic shock, and even death can occur within a few hours.

Diseases causing cholera-like symptoms have been known to exist since the 5th century B.C. One of the first detailed accounts of what was probably a cholera epidemic comes from Gaspar Correia, a Portuguese explorer, who described in 1543 an outbreak amongst army troops in Calicut and Goa; 20,000 deaths were ascribed to it. Over the coming centuries, Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British observers reported many such outbreaks in the country. Cholera Morbus, as called by the British, or mort-de-chien (dog’s death) by the French, was much feared for its virulence.

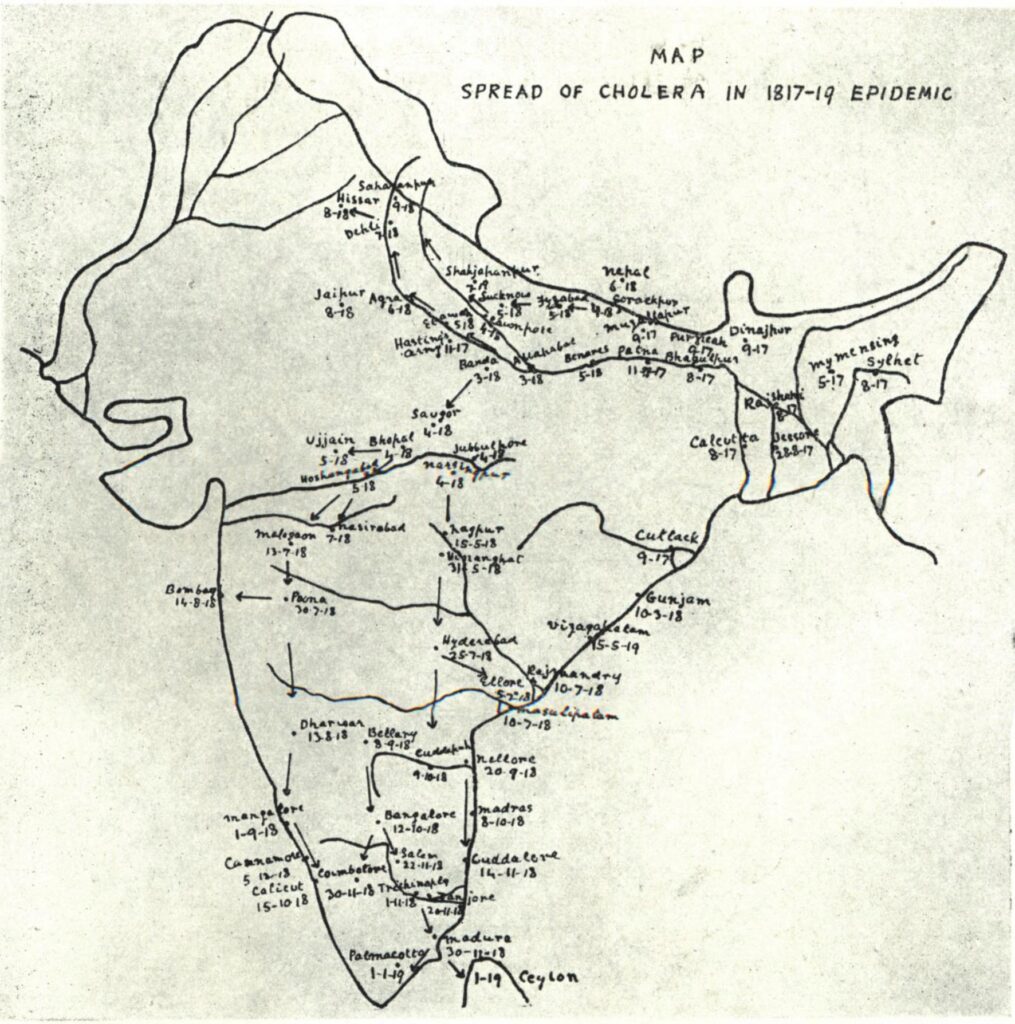

In 1817, the cholera-causing bacterium seems to have mutated. The new potent strain set about wreaking havoc. Outbreaks were reported from May and by August, the disease had firmly established itself in many parts of Bengal province (comprising places in modern India – Assam, West Bengal, Bihar, and north Orissa – as well as Bangladesh).

Transportation was slow then; nevertheless, in about 16 months, soldiers, pilgrims, and traders had carried the disease to most parts of the country (Figure 1).

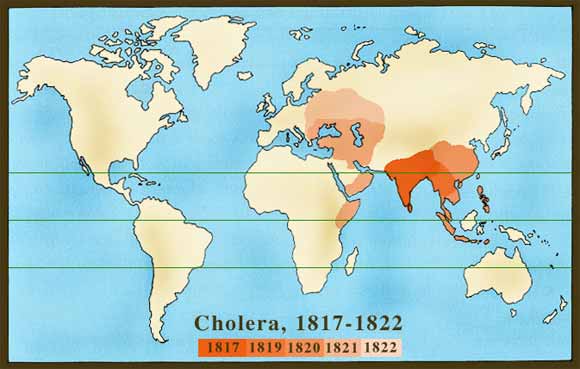

From India, cholera spread to Siam (Thailand), Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), and Philippines. From there, it made its way to China in 1820 and Japan in 1822 by way of infected people on ships. In 1821, British troops traveling from India to Oman and traders between India and the Middle East brought it to the Persian Gulf. The disease eventually made its way from Persia (Iran) to European territory, reaching modern-day Turkey, Syria, and Southern Russia. The severe winter of 1823-24 killed the bacteria living in water and stopped the pandemic at the doorsteps of Europe (Figure 2).

It is not known how many died during the First Pandemic. Possibly upwards of 1-2 million, most of them in India. In the six cholera pandemics between 1817 and 1920, 19 million are estimated to have succumbed worldwide; of this, India at 8 million and Russia at 3 million were the hardest hit. Another 30 million died in India because of the disease’s endemicity.

War before Peace

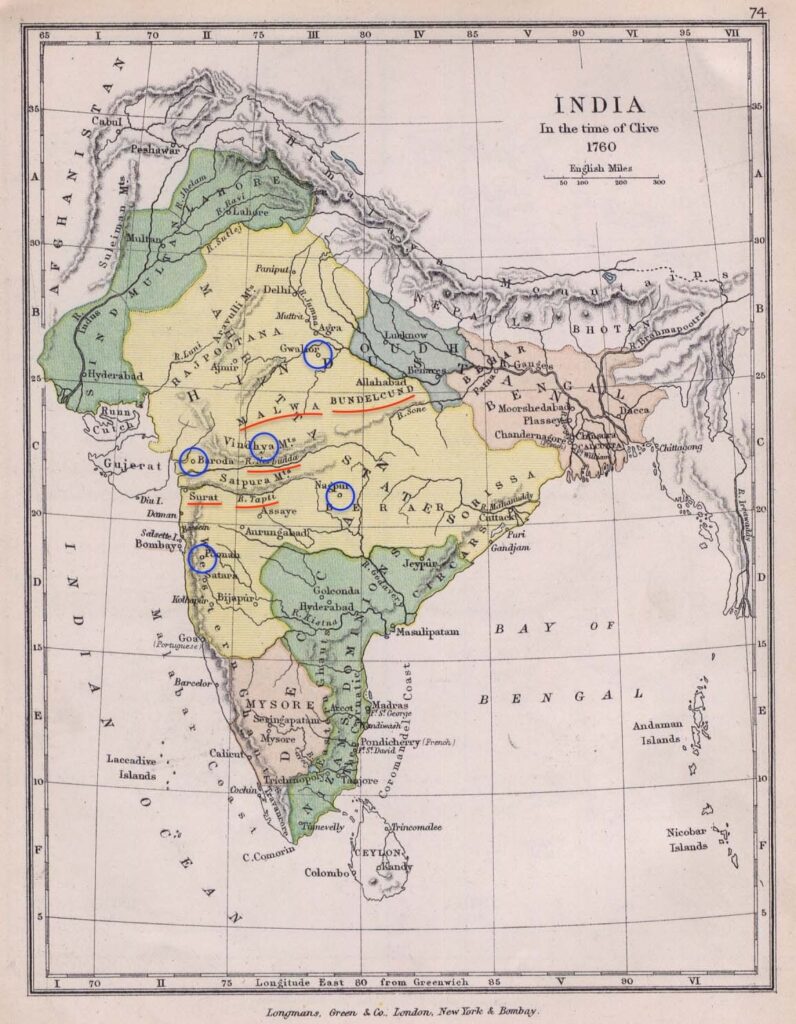

In their heydays, the Maratha Confederacy (also known as the Maratha Empire) controlled large parts of central and north India (Figure 3).

The Maratha Confederacy, or Maratha Empire comprised the realms of the Peshwa and four major independent Maratha states, often subordinate to the former. The Peshwa or hereditary Prime Minister, with his capital at Poona, was generally considered as its leader. The four states were ruled by different families – the Scindias (or Shinde) of Gwalior, the Holkars of Indore, the Bhonsles of Nagpur, and Gaekwads of Baroda.

Figure 3. ‘India in the time of Clive 1760’. The country was under various Indian dynasties, of which the Maratha Confederacy was the most dominant. Meanwhile, the rule of the once-great Mughals did not extend much beyond the Red Fort of Delhi! Poona and the capitals of the four Maratha chiefs are circled in blue (Indore is not on the map but it is to the east of Baroda and marked approximately). Malwa (home of the Pindaris) and Bundelcund (where Hastings Camp was) are underlined.

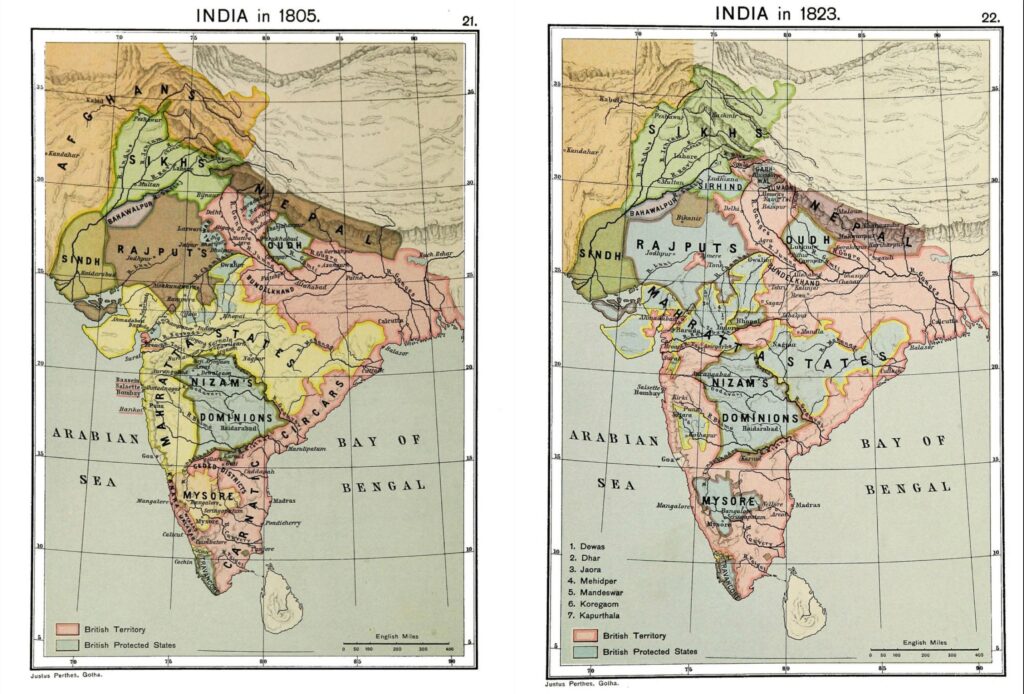

Going into the second decade of the 1800s, British hegemony over India had grown leaps and bounds. The Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803-05 had reduced the Confederacy to a shadow of their former self (Figure 4 left). The culmination of the Third Anglo-Maratha War of 1817-19 saw almost all parts of the peninsula come under the control of the East India Company (Figure 4 right), either directly or by exercising suzerainty over Indian states. A long-period of relative peace followed.

Conflict with the Pindaris

An event running in parallel to the Anglo-Maratha War was the Pindari War of 1817-18.

The Pindaris2 were groups of loosely organised horsemen comprising of different castes and classes (Hindus and Muslims; Afghans, Jats, and Marathas). After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Mughal Empire deteriorated rapidly. The Pindaris came into their own aligning themselves loosely with the Marathas, for whom they provided reconnaissance, supply, and raiding capabilities. They were allowed to plunder in lieu of pay.

From a position of extreme domination in the 1760s, the coming decades saw the Maratha chiefs grow increasingly weak; lack of unity amongst them was exploited by the British. The Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803-05 saw them lose much land and consequently, revenue. Administration suffered. Amidst the chaos and anarchy arising from a lack of strong and effective rule, the Pindaris became largely a law unto themselves; even the Maratha leadership were unable to exert much control over them.

They operated from Malwa (current day north and west Madhya Pradesh and south-east Rajasthan) from where they conducted their winter raids, starting after the festival of Dussehra (falling in late October or early November) every year. Looting, burning, raping, and even slaving, they made life miserable for the countryside. Their cruelty was so severe that inhabitants of whole villages sacrificed themselves rather than see their wives and children falling into the marauders’ hands (Figure 5). The spoils being too alluring, their numbers increased from around 10,000 (just 2,250 according to another estimate) in 1800 to 25,000-30,000 in 1814.

In 1812, the Pindaris made their first incursion into British-held areas in the north near Mirzapur. During the winter of 1812-13, they raided the area around Surat in western India. In February 1816, they came to the south, plundering mainly in the Guntur and Cuddapah districts.

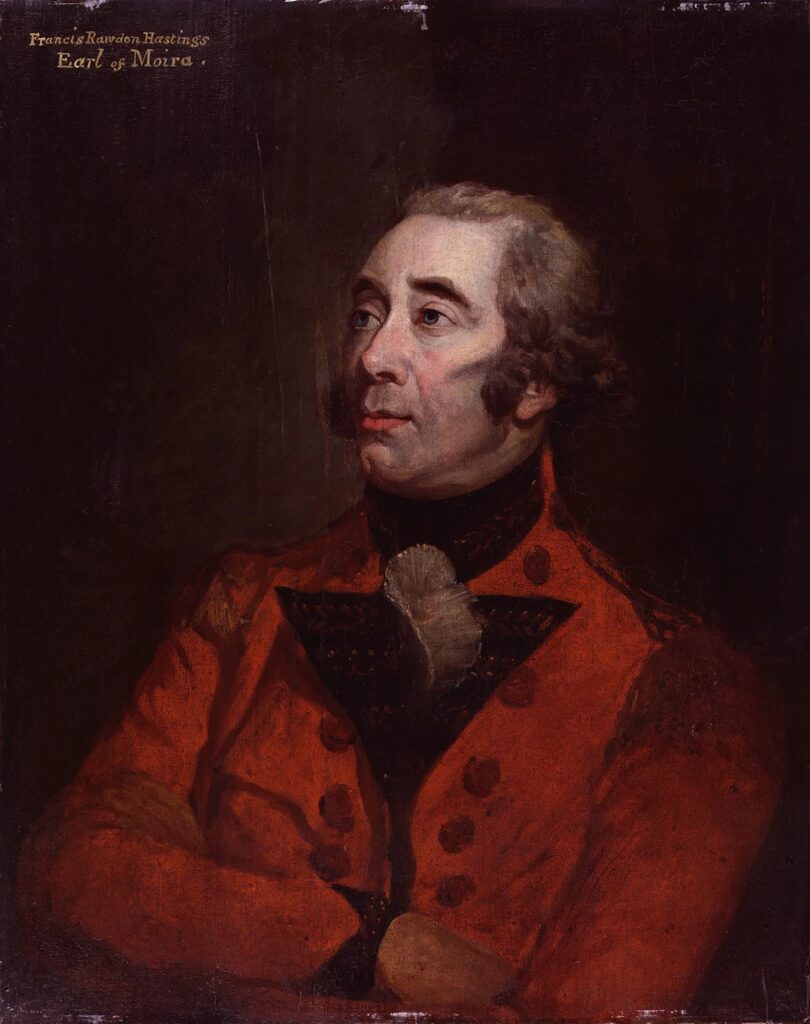

Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings, (Figure 6) arrived in India as the new Governor-General in October 1813. Initially, he did not get support from either the Council in Calcutta or from the Company’s Court of Directors in London to go after the freebooters. Following the raids of 1815-16, they permitted him to take the necessary steps to eliminate the lawless criminals.

Hastings decided to kill two birds with one stone – decimate the raiders and cut Scindia and Holkar, their supposed benefactors, to size.

He signed treaties with the various Rajput and other states around the Pindaris and obtained their cooperation against the marauders; he even got Scindia to sign a treaty in late-1817.

At the same time, Hastings raised a large force of about 120,000 men. A veteran of the American War of Independence (he served there between 1775 and 81), he headed four divisions of the northern army himself. He entrusted five divisions of the ‘Army of the Deccan’ to Sir Thomas Hislop (1764-1843). In November 1817, the northern army entered Malwa; after some time, Hislop’s army too crossed the Nerbudda (Narmada River) (see Figure 2) from the south. By February 1818, the Pindaris had been cornered and largely defeated.

Cholera harasses Hastings!

As man prepared to battle each another, the bacteria causing cholera decided to wage war on man!

In the second week of November 1817, during the preparatory stages of the campaign, cholera hit Hastings’ centre division. They were then camped near the banks of Sinde in Bundelkhand (see ‘Hasting’s army 11-17’ just below ‘Agra’ in Figure 1).

A report (Jameson 1820, p.12-17) later drawn up on the order of the Bengal Government noted that at the camp:

…the disease put forth all its strength, and assumed its most deadly and appalling form…After creeping about, however, in its wonted insidious manner, for several days among the lower classes of the Camp followers; it, as it were in an instant, gained fresh vigour, and at once burst forth with irresistible violence in every direction…it surpassed the plague in the width of its range; and outstripped the most fatal diseases, hitherto known, in the destructive rapidity of its progress…The whole camp then put on the appearance of a hospital…mortality latterly become so great, that there was neither time nor hands to carry off the bodies; which were then thrown into the neighbouring ravines, or hastily committed to the earth, on the spots in which they had expired…

Of 11,500 fighting men of all descriptions, 764 fell victim. Amongst the camp followers, about 8,000 died. Hastings took the decision to move camp in search of healthier soil and air.3 About 50 miles away, they found more favourable country and the change of air proved beneficial.4

In a short while, they started their campaign by defeating a group of Pindaris, who were on the march to Gwalior at the invitation of Scindia. Hastings later wrote:

A few days’ longer continuance of the Epidemik might, by entirely crippling this Division, have given a very different appearance to the face of affairs, and prolonged the struggle to an indefinite period.

The disease subsequently turned north as well as south reaching Poona in July 1818 (see Figure 1).

An Officer Writes Home

I collect letters for their postal history (i.e. postal rates, routes, regulations, and modes of carriage). However, many items, especially entire letters, contain contemporary news, and I generally find them to be interesting read. Letters from India written home during the first few years of the Pandemic5 often portray a sense of hopelessness and resignation.

My favourite letter, from a postal history as well as contents perspective, is one from August 1818 written at Seroor, which lies 40 miles north-east from Poona. It covers all what we have talked about – Pindaris, Marathas, and cholera. In addition, it is a very early letter written just as cholera was breaking out in that place for the very first time.

From Lieutenant George Maquay (Macquay) of the 4th Regiment Madras Native Cavalry, it was addressed to his uncle, John Lekind Maquay of Dublin. Maquay’s regiment was part of the Fourth Division of the Army of the Deccan, which was commanded by Brigadier-General Lionel Smith (1778–1842); they were mostly involved in operations against the Peshwa.

On the Pindaris he says:

…all India appears to be quiet at present and likely to remain so – altho I think it is not unlikely are old friends the Pindaris may pay us another visit in the cold weather – the great body of them are certainly put down for the present but there are always a number of marauding rascals in the Maharatta states who have no employment and who will not cultivate the ground for their support…these fellows have all their lives as well as their Fathers and Grandfathers lived by plunder and it must be a work of time to turn their hands to some useful occupation. I am however in hopes they may confine their occupations to the North end of the Nerbudduh. The company have taken into their pay merely to keep them out of mischief a great body of Maharatta horse. I am not sure exactly the numbers but I believe all together about twenty thousand…these men get 40 rupees a month which is about three shillings a day…this you will say is an immense establishment but they are very useful in their way and it is not intended to fill up the casualties but allow them to die off and the company are amply remunerated by the great accession of territory they have got in the late war.

What is interesting to note here is that the Pindari leaders and their followers were rehabilitated so that they did not go back to their old ways. The Company paid them pensions and gave them land to settle in.

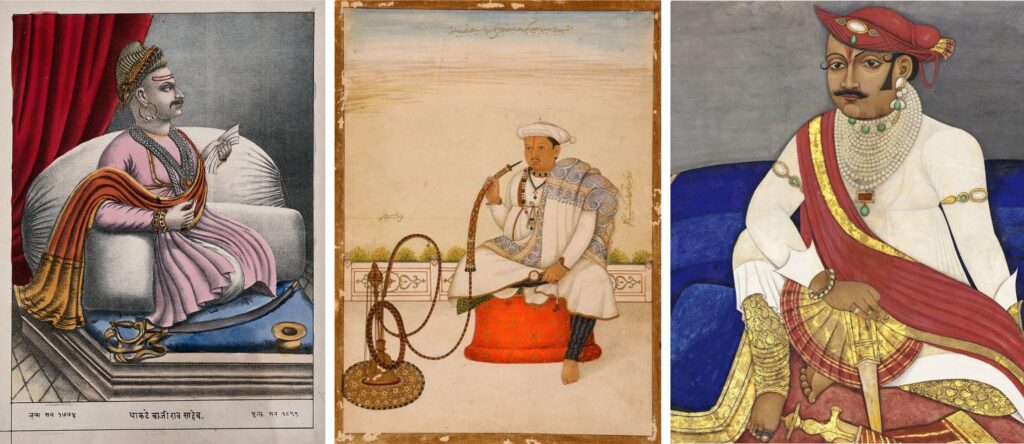

Next, Maquay talks about how the various Maratha chiefs (Figure 7) – Peshwa, Holkar, and Bhonsle (of Berar) – have been brought to their knees.

They have got the whole of the late Peshwah’s Country which was the finest of any of the Mahratta powers – all Holcur’s south of a range of hills running parallel to & north of the Tapte river together with large tracts of Country ceded by the Rajah of Berar. The Peshwah has been sent to Benares in Hindustan and has got a yearly pension of about one hundred and twenty thousand pounds per annum. The late Rajah of Berar whose capital was Nagpoor made his escape some time back and is now wandering about the jungles with a few followers but no money….Holcur is merely the shadow of what he was before the battle of Madedpurr and can now be scarcely considered one of the principal Maharatta power – and has been obliged allow a British resident to be fixed at his Court and military offices to command his best Troops – Scindia is therefore left alone and has been so long thinking of it that he will scarcely break out now…He has likewise been obliged to give the command of some of his best Troops to our officers and none of the Maharatta Powers are allowed according to Treaty to permit any Bodily Troops to move about the Country – I mean about their own country without permission of the Residents in their respective courts –

The British defeated the Maratha chiefs within a few months of the war starting on 5 November 1817.6 However, the war dragged on until April 1819 since several Maratha forts were still holding out under the command of their qiladars (governor or chieftain of a large fort or town).

Finally, he comes to cholera:

The Cholera Murbus which I then mentioned (a previous letter written “a very short time” earlier) as having reached this place has not been so very fatal in its effects as elsewhere. We have lost about twenty 8 [unclear] soldiers but not an equal proportion of Natives and I think it is now leaving us – No officer has died and but few been attacked of which number I was not one…

Maquay does not sound too melancholic probably since he escaped being infected and his regiment was not as badly hit as some others. It is thought that about 10,000 troops in British service (which likely includes Indians) died during 1817-23. Another estimate put the total number of British soldiers who succumbed to the disease between 1818 and 1854 at 8,500.

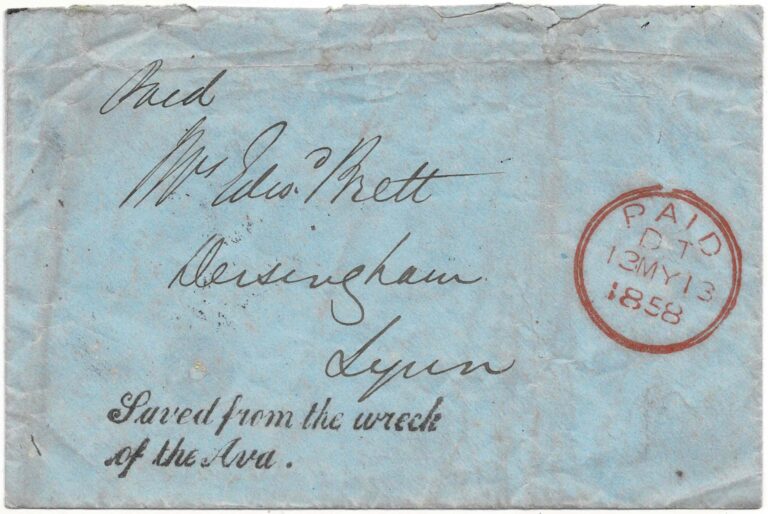

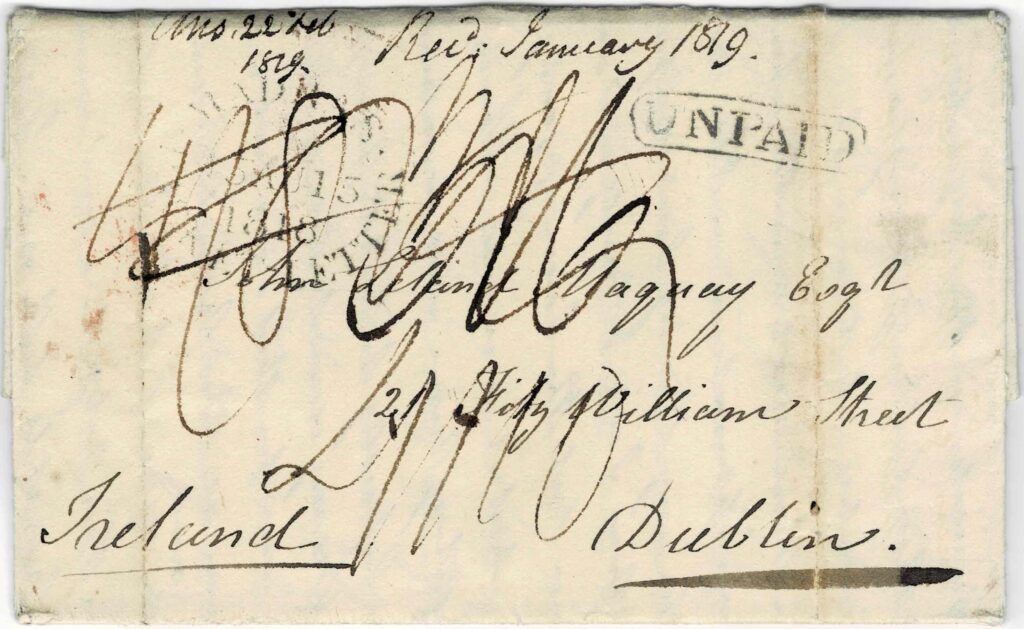

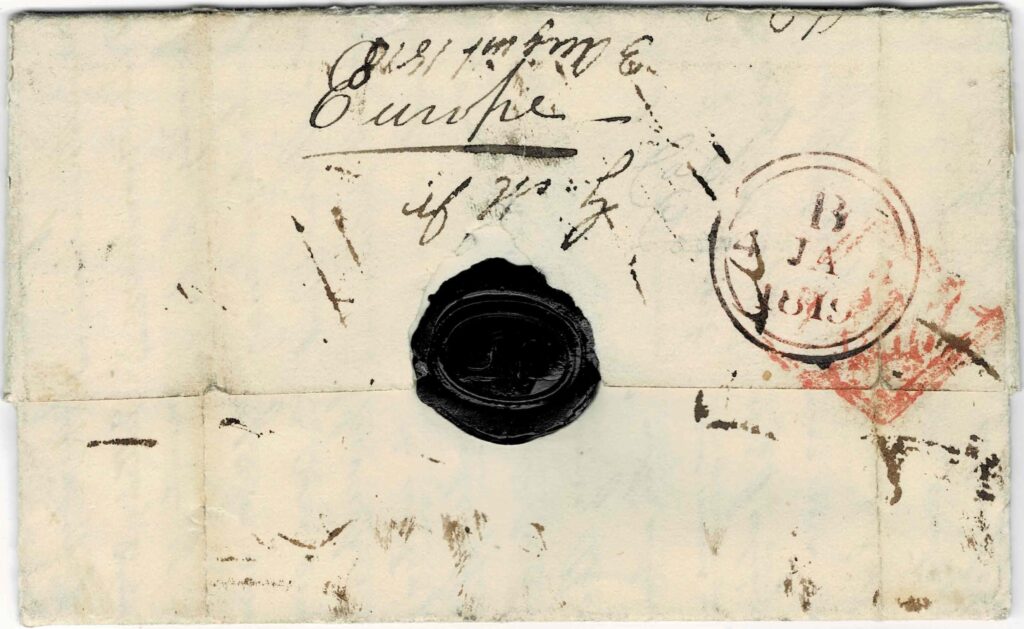

The said letter is shown in Figure 8. Coming to its postal history, lack of manuscript endorsements or handstamps makes it likely that it was carried along with the regiment’s official despatches from Seroor to Madras. Thus, the sender did not have to pay inland postage for the 830 miles between the two places.

Maquay may have decided not to send the letter to the closer port of Bombay, just 130 miles away, for two reasons. One, at this time more ships sailed home from Madras than Bombay. Two, he would have had to pay inland postage since his letter would go through the Post Office.

When put into the Madras GPO, an oval ‘MADRAS / PACKET LETTER’ handstamp of 15 August as well as an ‘UNPAID’ was impressed upon the letter. The former suggests that the letter was being sent on a packet ship and the latter signifies that packet postage7 of 3s6d was not paid on this single letter by the sender.

The black manuscript ‘4/10’ stands for postage due of 4s10d in Irish money on this single letter containing one sheet and weighing less than 1 oz. The Irish currency was different from British money by one penny in the shilling (1 English shilling = 13 Irish pence). However, letters known from that period show that differences in the value of the two currencies were ignored by the Post Office (Robinson 1990, p.52).

4s10d Irish/British money was the sum of the following:

- British rate of 3s6d sent by Packet Ship from India to GB, plus

- 1s British rate from London to the port town of Holyhead in Wales (230-300 miles; 267 miles), plus

- 2d British packet postage across the Irish Sea from Holyhead to Howth, plus

- 2d Irish inland postage from Howth to Dublin (Below 7 miles; 3 miles)

For the purposes of the 1815 Act, inland postage in GB on ship letters was calculated from the port of disembarkation to London to the recipient’s town whereas on packet letters was calculated from London to the recipient’s town. Since this was a packet letter, no inland postage was charged for the carriage from Falmouth (where the ship docked) to London.

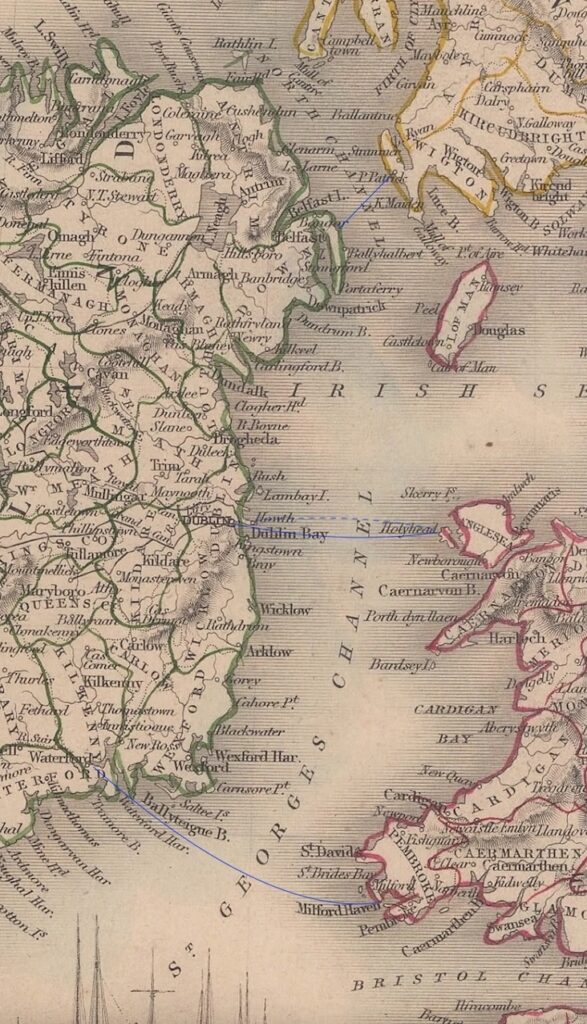

Interestingly, for a few weeks in June-July 1813 and between July 1818 and July 1819, packets berthed at Howth, 3 Irish miles (1 Irish mile = 1.27 British miles) from Dublin (Figure 9). Inland postage in Ireland was calculated to and from Howth and not Dublin which added 2d.

References

Harrison, Mark. 2020. “A Dreadful Scourge: Cholera in early nineteenth-century India.” Modern Asian Studies 54 no. 2 (March): 502 – 553.

Jameson, James. 1820. Report on the Epidemick Cholera Morbus, as it visited the Territories Subject to the President of Bengal, in the years 1817, 1818, and 1819. Calcutta: Medical Board.

Joppen, S. J. Charles. 1907. Historical Atlas of India for the Use of High Schools, Colleges, and Private Students. Bombay: Longmans, Green & Co.

McEldowney, Philip F. 1966. “Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India.” Master of Arts (History) Thesis, University of Wisconsin

———. 1971. “A Brief Study of the Pindaris of Madhya Pradesh.” The India Cultures Quarterly 27 no. 2 (Quarter Two): 55-70.

Robinson, David. 1990. For the Port & Carriage of Letters: A Practical Guide to the Inland and Foreign Postage Rates of the British Isles 1570 to 1840. Kilmacolm, Scotland: The Author.

Rogers, Leonard. 1927. “The Forecasting and Control of Cholera Epidemics in India.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 75 no. 3874 (18 February): 322-355.

Tumbe, Chinmay. 2020. The Age of Pandemics 1817-1920. How they Shaped India and the World. Noida, India: HarperCollins Publishers India.

Endnotes

- The First Cholera Pandemic lasted 1817-23. The world was hit with six more of them (1826-37, 1845-60, 1863-75, 1881-96, 1899-1923, 1961-present). By the 1850s, cholera had reached most parts of the globe. Even today, as per the WHO, cholera infects between 1.3 and 4 million people and kills 21,000-143,000 people every year.

Incidentally, Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera is set between the late 1870s and the early 1930s in a South American community beset by wars and outbreaks of cholera. ↩︎ - McEldowney (1966) provides a superb investigation into the Pindaris – their history, social and military organisation, their raids, and their suppression by the British. Those who want a shorter read can look up his 1971 article. ↩︎

- At this time the belief was that the disease was caused by ‘miasma’ i.e. noxious or bad air, which emanated from rotting organic matter. The germ responsible for cholera was discovered twice: first by the Italian physician Filippo Pacini during an outbreak in Florence, Italy, in 1854, and then independently by Robert Koch in India in 1883, thus favoring the germ theory over the miasma theory of disease. ↩︎

- Jameson (1820, p.17) says that in Hastings’ camp a few mild cases were seen daily after 22 or 23 November and none after 8 December 1817. Rather than healthy air, what seems to have helped is that the disease became endemic. ↩︎

- There was no disinfection of such letters being carried out then. ↩︎

- Gaekwad remained neutral in both the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha wars. Scindia too did go to war during the Third, reluctantly so, since he had signed the Treaty of Gwalior, coincidentally on the same day that war erupted between the Peshwa and British i.e. 5 November 1817. ↩︎

- Between 1815 and 1819, the Postage Act of 1815 (55 Geo 3 c. 153 dated 11 July 1815; also known as the ‘India Packet Letter Act’ or ‘King’s Post Act’) was in force. Discussing this Act is beyond the scope of this article and readers can find more information in one of my earlier articles on this subject. ↩︎