The title of this post has been inspired from that 2017 movie’ quirky title: Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri.

For centuries, countries in Europe were at loggerheads resulting in innumerable wars. While history remembers the generals and admirals who won laurels, wars couldn’t have been fought without the poorly paid and much neglected soldiers and seamen.

1792 saw the beginning of what was later recognised as the French Revolutionary Wars. To boost the morale of soldiers and seamen serving in the British expeditionary force in Holland (Flanders campaign of 1793-95), steps were initiated in Great Britain (GB) in 1794 to reduce postage rates applicable on their letters. Ironically only a small percentage of them were literate enough to pen their own epistles!

Legal Background

By virtue of an act of the British Parliament (35 George III c.53, 5 May 1795), soldiers and seamen serving in His Majesty’s army and navy respectively were allowed to send and receive single letters (i.e. letters containing one sheet of paper) at a 1d concessionary rate of postage.1

In 1806 (46 Geo 3 c.92, 16 July 1806), the privilege was extended to the following categories of non-commissioned officers: “Serjeant, Corporal, Drummer, Trumpeter, Fifer, and Private Soldier, in His Majesty’s Regular Forces, Militia, Fencible Regiments, Artillery, or Royal Marines”.

By an act (55 George III c.153, 11 July 1815) popularly known as ‘India Packet Letter Act’ or ‘King’s Postage Act’ or ‘East India Postage Act’, the 1d concession was extended to soldiers and seamen employed in the East Indies or in the service of the East India Company (EIC).2

When this act was replaced by another (59 Geo 3 c.111, 12 July 1819), popularly known as the ‘India Letter Act’, its sloppy drafting meant there was no clause which catered to such letters. Soldiers and seamen of HM forces stationed in East Indies as well as those serving the EIC lost this privilege. Their letters were subject to the same rates of postage as private individuals.

The concession was reinstated four years later when the East India Company’s Service Act (4 Geo 4 c.81, 18 July 1823) was passed.3

A treasury warrant dated 27 December 1839, which introduced penny postage in UK, changed the definition of ‘single letter’ to one weighing ½ oz or less effective 10 January 1840.

Postage Rates

Postage rates on soldiers’ letters between GB and colonies ranged from 1d to 4d, depending on when they were sent, whether they were sent prepaid or bearing, and whether they were carried by a private ship or packet ship/steamer. The rate included inland rates in GB and the colony concerned as well as sea postage between the two places.

Foreign rates of postage were additional. For example, a letter if sent from India to GB via France would need to pay French transit charges.4 And, as we will see later, US inland postage would be added to letters from India to US via GB.

The Four Letters

Most soldiers and seamen stationed in the East Indies (which term didn’t mean just the Indian subcontinent but also the Far East) or serving the EIC were from GB; it follows that their letters were to or from their family or friends in GB.

Hence, letters from India to GB, from the mid-1820s on, aren’t uncommon by any means. Incoming letters to India are scarcer, as they are less likely to have been preserved and taken back by the soldier when he went home.

Scarce to rare are letters from (to) India to (from) countries apart from GB. Unless a soldier’s family or friends were living there, there wouldn’t have been any reason for him to write (receive) letters to (from) there.

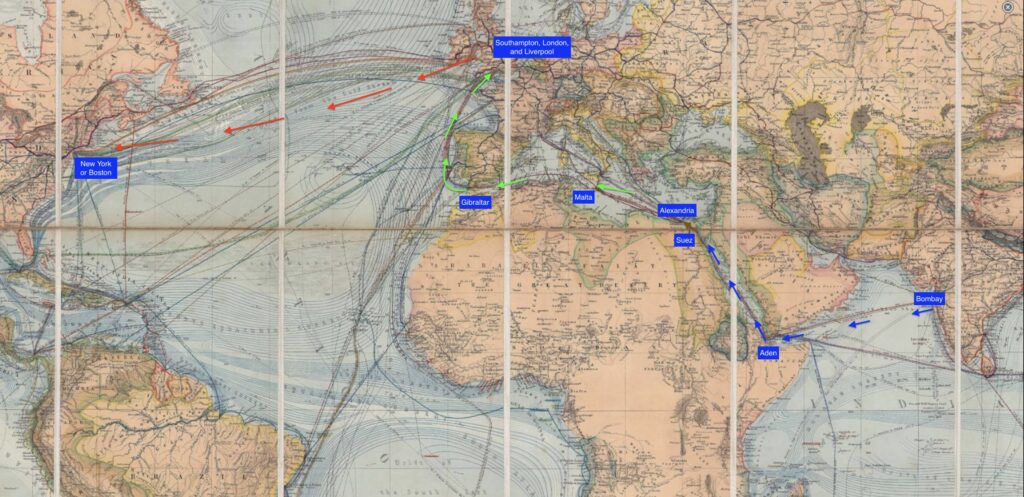

In this post, I will illustrate and describe four soldiers’ letters from India to the US. All are from the same correspondence and were sent between 1853 and 1856.5 Figure 1 shows the route taken by these letters to reach their destination 10,000 miles away.

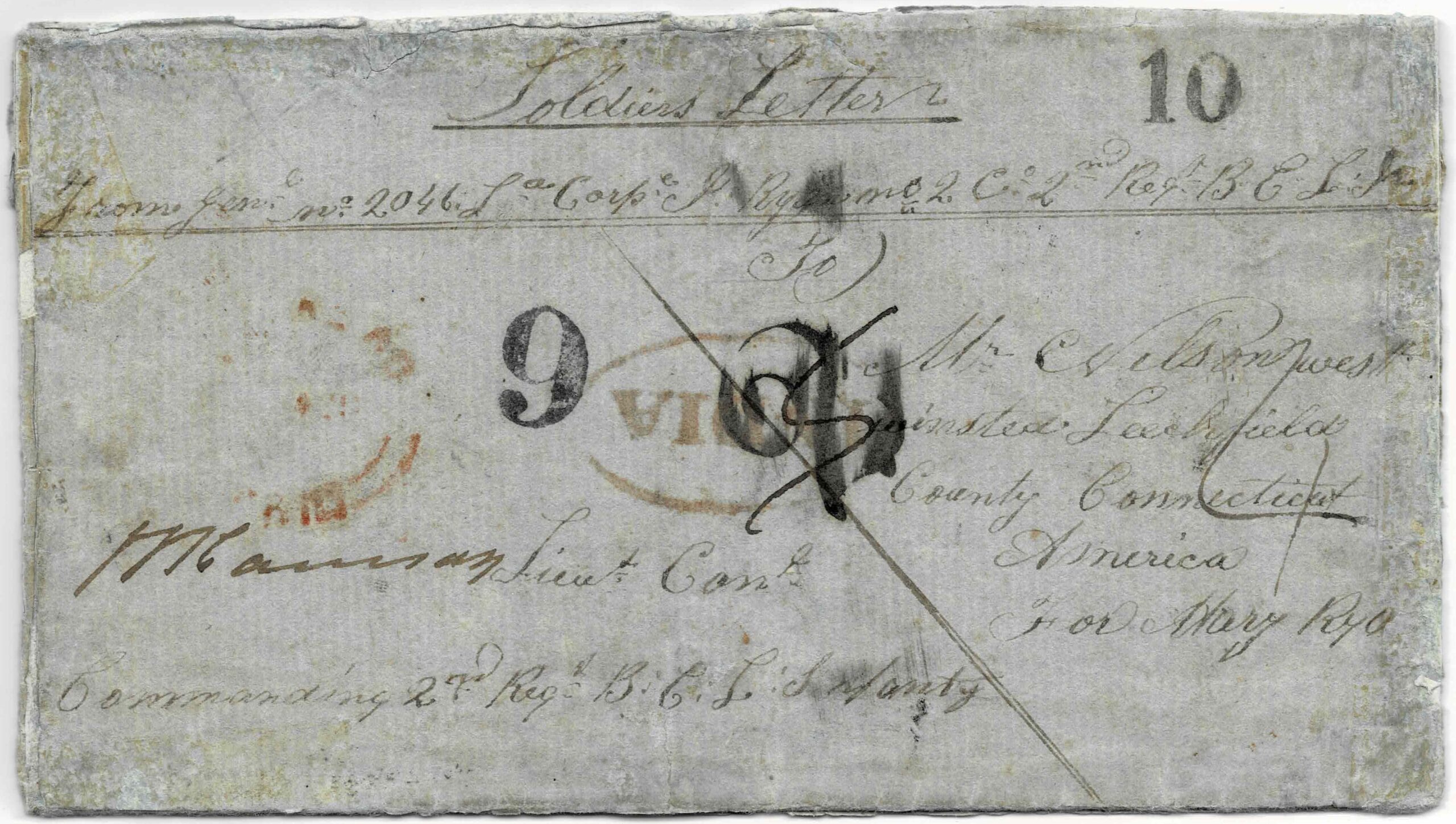

#1, April 1853: Belgaum to Westwinstead, Connecticut

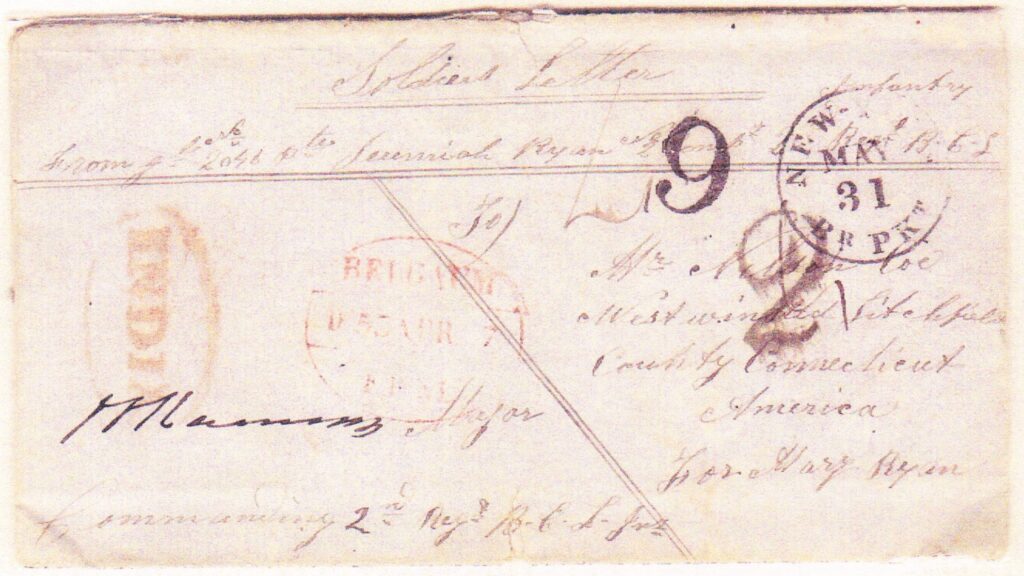

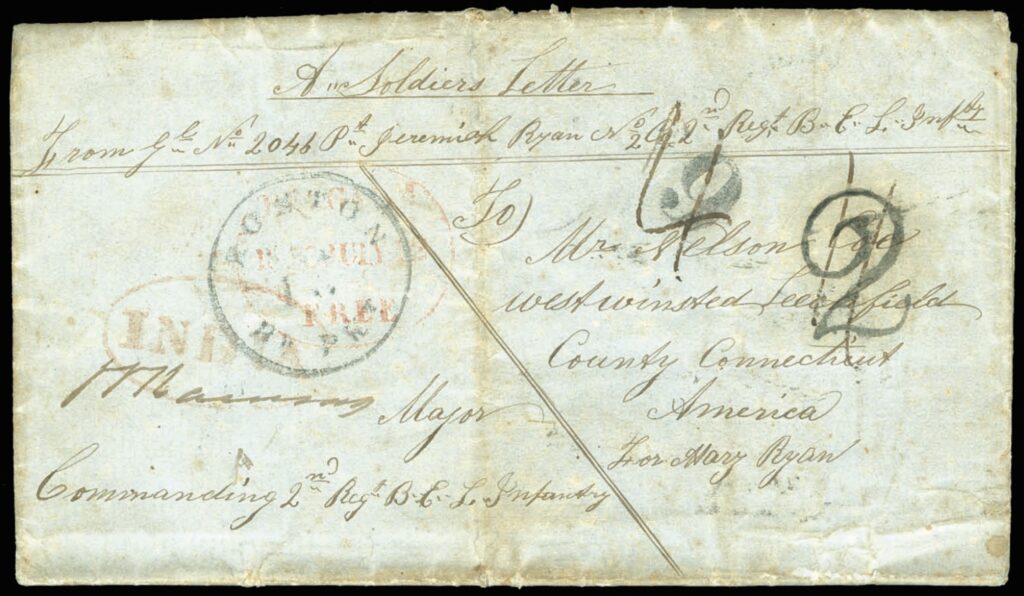

Figure 2 shows the first of the four soldiers’ letters. Datelined 5 April 1853, the letter was written by Private Jeremiah Ryan of the 2nd Company, 2nd Regiment, Bombay European Light Infantry. The recipient is mentioned as Mr. Nilson Coe but as the last line clarifies, all these letters were meant for the writer’s sister, Mary Ryan.

Routing: (1) Belgaum (7 April 1853) to Bombay overland (2) Bombay (14 April) to Aden (23 April) on EIC Queen (3) Aden (26 April) to Suez (2 May) on P&O Hindostan (4) Overland across Egypt to Alexandria (5) Alexandria (6 May) to Southampton (19 May) via Malta (9-10 May) and Gibraltar (14 May) on P&O Indus (6) Southampton to London (19 May) overland (7) London to Liverpool overland (9) Liverpool (21 May) to New York (31 May 1853) on Cunard Line Arabia (9) New York to Westwinstead, Connecticut, USA overland

As the rules governing soldiers’ letters required, it was countersigned by the Ryan’s commanding officer, Major John Skardon Ramsay, at the bottom left.

The letter was posted at Belgaum and was handstamped with a red oval BELGAUM/1853 APR 7/FREE postmark. The FREE mark identified the letter as one which didn’t need to pay any inland postage in India.

Thereafter, it was forwarded to Bombay where it received a red small oval INDIA handstamp,6 which was applied on all ‘unpaid’ letters; ‘unpaid’ in this context means that the letter didn’t pay the steam postage rate between India and GB. By this time, almost all mails between India and GB were carried by packet steamers.

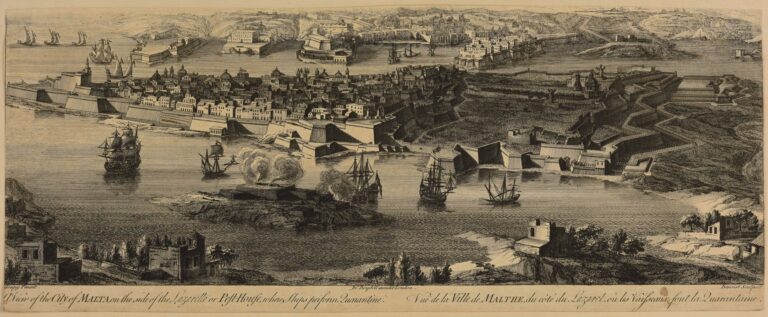

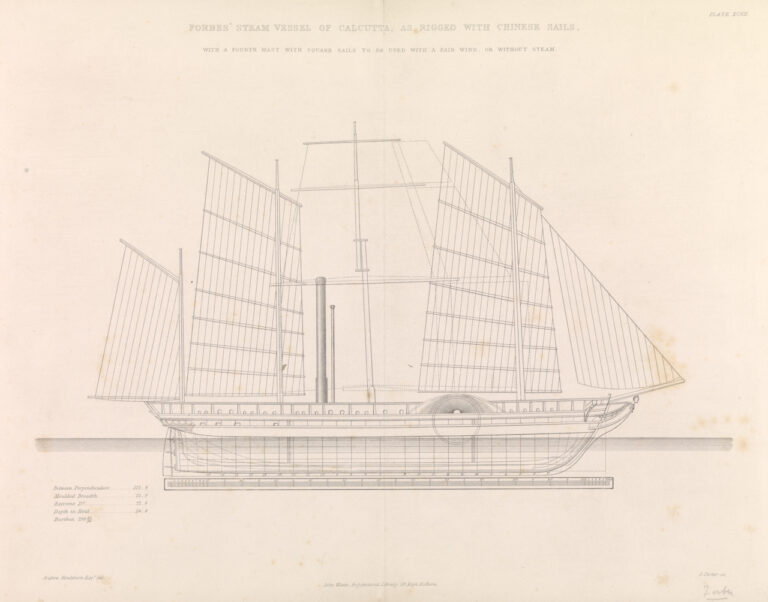

So, this letter took the EIC steamer Queen to Suez and subsequently went overland across Egypt to Alexandria. At that place, it was placed onboard another steamer, Indus, going to Southampton; she belonged to the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) (Figure 3).

From Southampton, the letter was taken to London where the black handstamp ‘2’ (later struck across) was applied. This meant a postage due of 2d i.e. 1d soldiers’ rate plus 1d penalty on unpaid letters brought in by a packet steamer. Since there was no way the British post office could recover the 2d in England, they marked in manuscript a debit of 4c (=2d) (to the left of the ‘9’) to their US counterpart.

The letter was sent to Liverpool to catch the steamer, Arabia, belonging to the British & North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (popularly known as Cunard Line for its founder, Samuel Cunard). This company had a long-term contract with the British admiralty for carrying mails.7

Arriving at New York on 31 May 1853, the letter received a black circular NEW-YORK/MAY/31/BR. PKT postmark (BR = British Packet) at the New York Exchange Office.

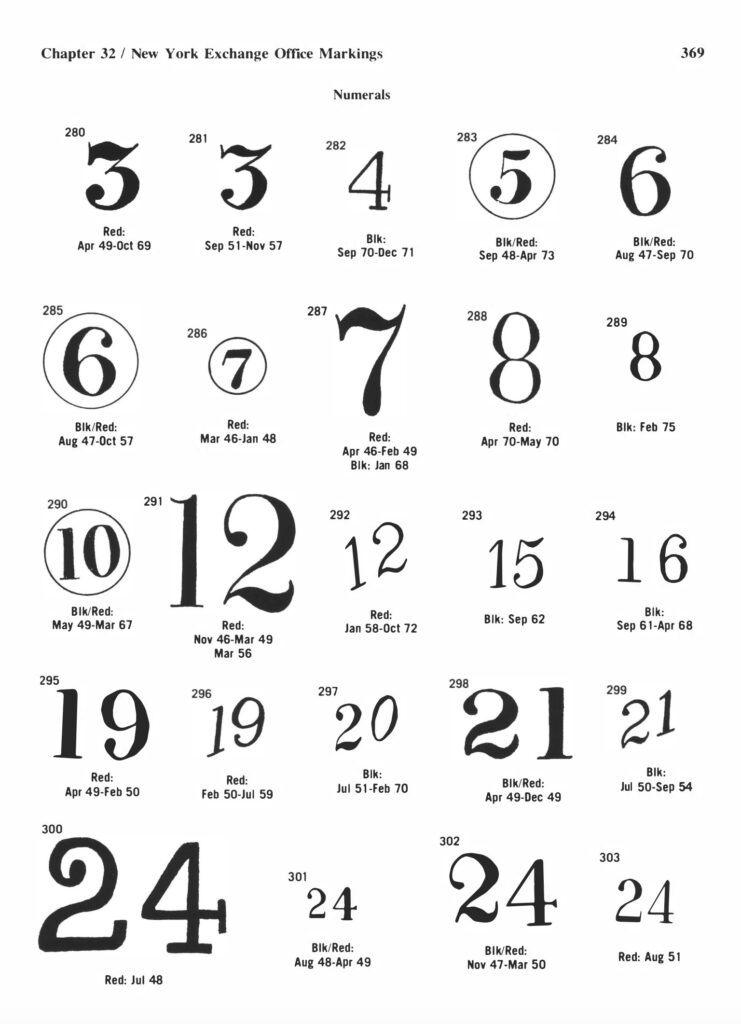

In an act of inspired improvisation by the same office, a black handstamp ‘6’ was struck, but upside down, to indicate a postage due of 9c which included US inland postage of 5c (Figure 4).8 Why? Because the postal clerk at that office didn’t have access to a handstamp for 9c (Figure 5)!

The letter would have been delivered to the recipient, Mary Ryan of Westwinstead, Connecticut, a day or two later. The total journey of 10,000 miles took less than two months. This was the magic of steam communications!

#2, July 1853: Belgaum to Westwinstead, Connecticut

Figure 6 illustrates another letter written two months after the one in Figure 2.

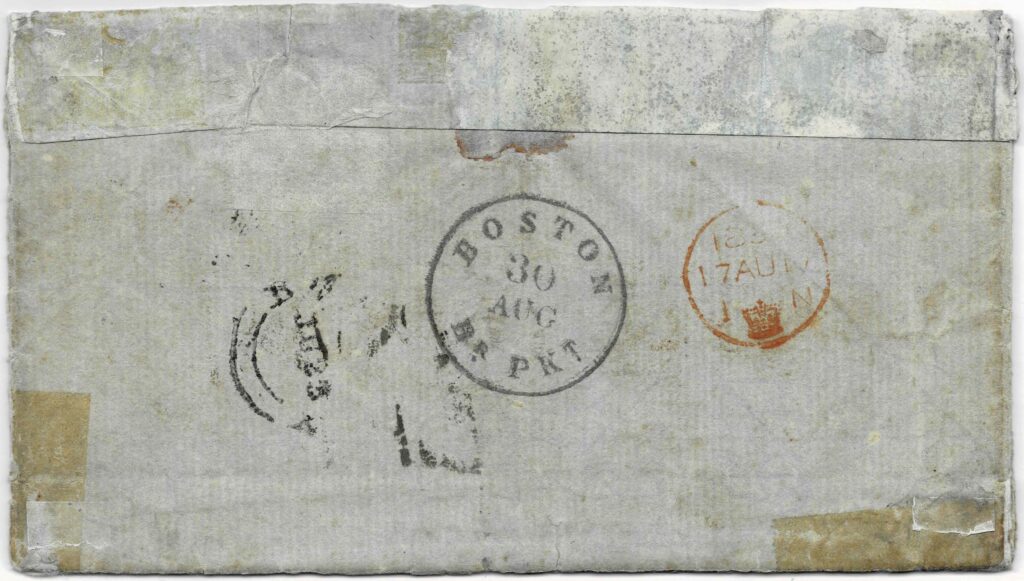

Routing: (1) Belgaum (12 July 1853) to Bombay overland (2) Bombay (20 July) to Aden (30 July) on EIC Semirramis II (3) Aden (7 August) to Suez (14 August) on P&O Bentinck (4) Overland across Egypt to Alexandria (5) Alexandria (19 August) to Southampton (2 September) via Malta (22-23 August) and Gibraltar (27-28 August) on P&O Ripon (6) Southampton to London (2 September) overland (7) London to Liverpool overland (9) Liverpool (3 September) to Boston (15 September 1853) on Cunard Line Niagara (9) New York to Westwinstead, Connecticut, USA overland

This letter is ex-Richard F. Winter (Figure 7), the great postal historian of Trans-Atlantic mails.

The postal markings are similar to the one discussed earlier:

- red oval BELGAUM/{Date}/FREE (under the Boston mark)

- small oval INDIA applied at Bombay

- ‘2’ (for 2d) and ‘4’ (for 4c debit by GB to US) both applied at London

- inverted ‘6’ (for 9c postage due) struck at Boston

The only difference is that this letter landed at Boston and not in New York as evidenced by the BOSTON/{Day}/{Month}/BR. PKT. Similar to the NY exchange office, the Boston office too wouldn’t have possessed a handstamp for 9c.

#3, June 1855: Camp Hyderabad, Scinde Province to Westwinstead, Connecticut

The next letter once belonged to Gerald Sattin (1927-2007) (Figure 8), the well-known collector of Soldiers’ Privilege Rates of the British Empire to 1898.

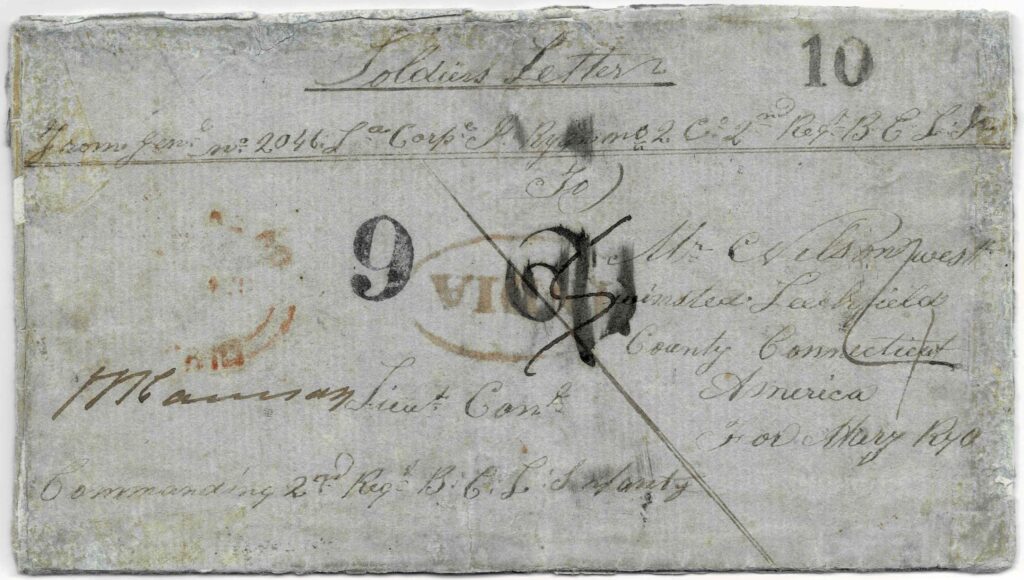

Both sides of the letter are shown as Figure 9. When he wrote this, Jeremiah has been promoted to Corporal. And his commanding officer, John Ramsay, to Lieutenant-Colonel.

The markings on this letter are similar to the previous two excepting that it was written from Hyderabad in Scinde province (partial strike of red HYDERABAD/{Date}/PAID). The black ‘10’ on top, is possibly the sum of ‘6’ and ‘4’ applied incorrectly by a US postal clerk; none of the other three letters are marked so.

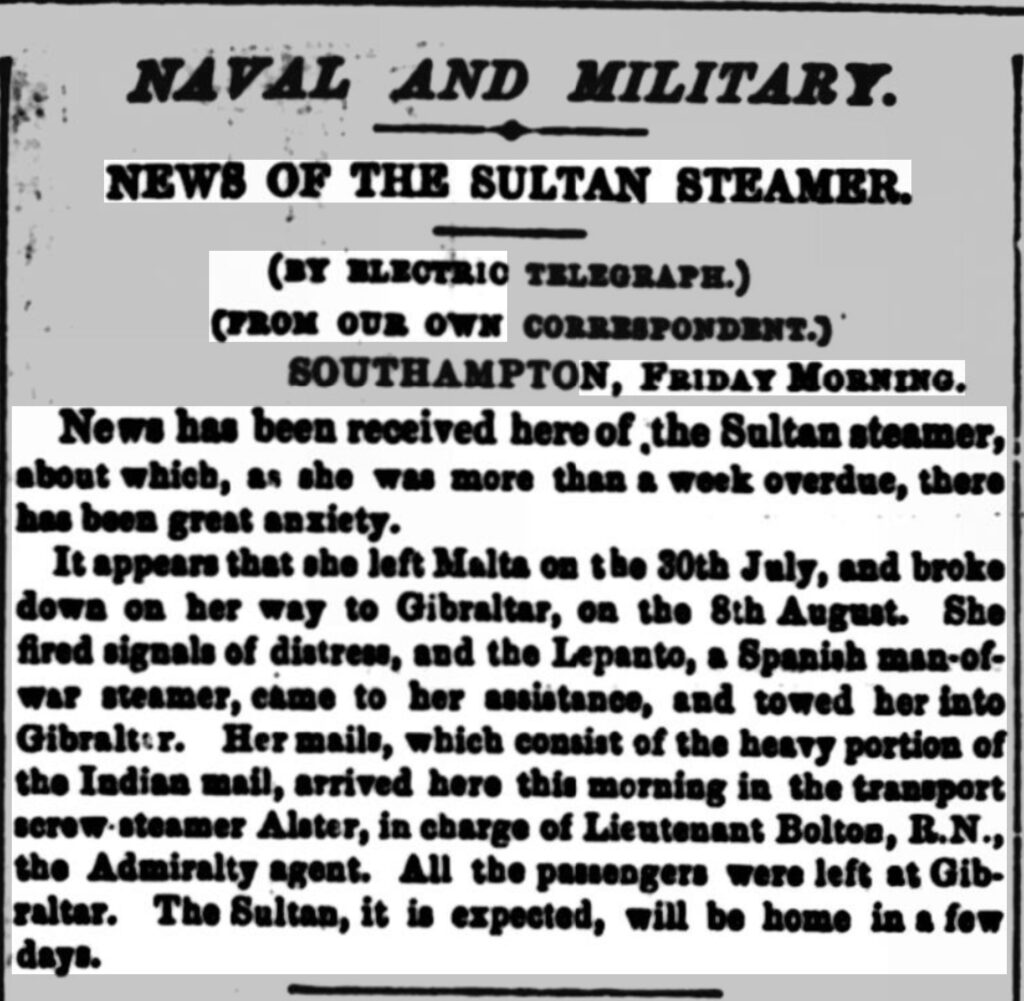

One interesting aspect about the routing is that the P&O Sultan failed to complete its Alexandria-Southampton voyage (‘failed voyage’ in postal history terms). It broke the crank-pin of her engines off Point de Gatt and had to be assisted into Gibraltar by Lepanto, a Spanish man-of-war steamship. Mails, but not her 67 passengers, were transferred at Gibraltar to SS Alster, which took them to Southampton (Figure 10).

I can produce the contents of this letter. The English is frequently improper and some of the spellings are wrong. There are hardly any full stops after sentences (which I have inserted); in some parts of the letter, the full stop is replaced by double commas.

There are a few interesting aspects to it. First, is is clear that brother and sister didn’t write to each other too often (which partly explains why only four letters of this correspondence have been found). Sample this:

I hope you will excuse me for not writing to you before now [.] certainly its my own fault but I hope it shall not be the case for the future [.] I assure you Dear Mary I will correspond with you for the time to come [.] I recd. a letter from you last July (i.e. July 1854) in Kurrachee and I never got one since.

how is it you never let me know whether you got married or not [.] I expect you are wherein you are so dilatory in writing, for generally when people gets married they scarcely think at all of any one belonging to them [.] Certainly I am neggligent (negligent) myself in writing but don’t run away with that idea that I am married as I made the remark for I assure you that I am not…I shall write to you next month (probably letter #4 shown below).

Secondly, Ryan talks about what transpired with him over the two years since he last wrote to her (possibly letter #2 above). Note the part where he says that the senior Captain got to go to the city of Bombay rather than Kurrachee; the former was obviously a more desirable location.

Dear Sister I wish to let you know that I traveled a great part of this Country since I write to you last from Belgaum [.] we left that Station on the 1st of December 53 to proceed to Kurrachee [.] we had 72 Miles to march to a place called Vingurla and then we had four days sail by the Steamer from there to Kurrachee [.] but when we came to Vingurla the Commanding officer recd. an order from the Co. in Chief of Bombay for to send one hundred men to the city of Bombay for to do duty…So No. 2 Compy. was selected there as the Captain who Comd. (commanded) it was the Seign. (senior) Captain….with the Regt. then and he had to go in Command of the Detachment, So the next morning we embarked on board of the Steamer and arrived in Bombay at 12 A.M. the following day….So we remained there for 4 months and we joined our Regt. on the 1st of April 54 in Kurrachee [.] So we remained there untill (until) 18th of December last when we marched to Hyderabad and arrived here on the 29th of the same months after one hundred and thirty five miles march. this is a very good station considering its name (joking about the ‘bad’ in Hyderabad!) but it is dreadfully hot…

Where were the Ryans from? Ireland.

I am informed that Ireland is getting on first rate that the potatoes are coming on as well as ever and great Demand for all sorts of commodities…

Did brother and sister ever meet again? I don’t know though Ryan certainly hoped so.

Dear Mary I hope we will meet again the time will not be long running over ,, write to me regular [.] I wd. (would) wish you wd. write to me at least twice a year [.] don’t be waiting for my letters at all [.] write to me whenever you have an opportunity for there is nothing in the word wd. give me more pleasure ad comfort that to hear from you [.] I wish to god I could hear from you daily,,

#4, June 1856: Camp Hyderabad, Scinde Province to Westwinstead, Connecticut

The fourth and last letter (Figure 11) was again written from Hyderabad a year later. On this occasion, the letter was countersigned by Major Edmond Arthur Guerin.

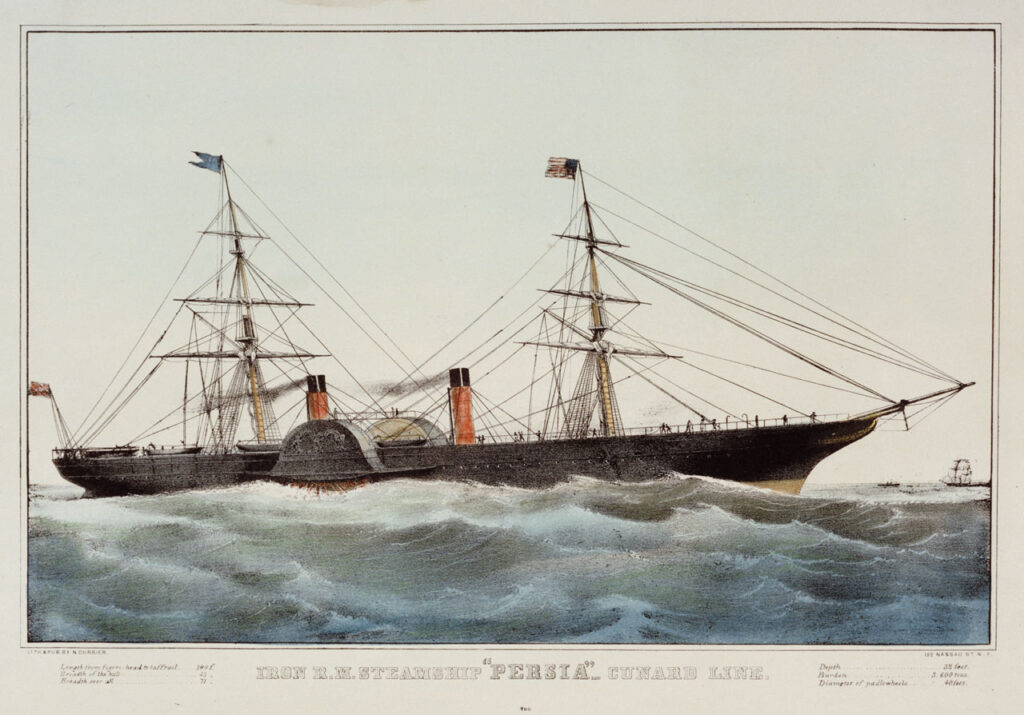

Routing: (1) Hyderabad (July 1855) to Bombay overland or via Kurrachee by sea (2) Bombay (11 July) to Aden (23 July) on P&O Norna (3) Aden (28 July) to Suez (4 August) on P&O Hindostan (4) Overland across Egypt to Alexandria (5) Alexandria (6 August) to Southampton (20 August) via Malta (10 August) and Gibraltar (15 August) on P&O Indus (6) Southampton to London (21 August) overland (8) London to Liverpool overland (9) Liverpool (23 August) to New York (3 September 1856) on Cunard Line Persia (10) New York to Westwinstead, Connecticut, USA overland

The letter arrived in New York on board the Cunard Line Persia (Figure 12). Rather than the inverted ‘6’ mark that we have seen in the previous letters, the postal clerk noted the postage due of 9c in black manuscript.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Richard Winter for helping me with a copy of the letter shown in Figure 1. It was the description is his sale catalogue that enabled me understand the British and US rate markings. Also, Max Smith and Martin Hosselmann for going through the draft of this and for their comments. Feedback is welcome; write in to abbh [at] hotmail.com.

References

- Giles, D. Hammond. Catalogue of the Handstruck Postage Stamps of India. London: Christie’s Robson Lowe, 1989.

- Hubbard, Walter, and Richard F. Winter. North Atlantic Mail Sailings 1840-75. Edited by Susan M. McDonald. Canton, Ohio: U.S. Philatelic Classics Society, Inc, 1988.

- Kirk, R. The P&O Bombay & Australian Lines 1852-1914. Vol. 1. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History. Heathfield, East Sussex: Postal History International (A Proud Bailey Division), 1981.

- ———. The P&O Lines to the Far East. Vol. 2. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 1982.

- Stitt-Dibden, W. G. Postal Rates of H. M. Forces 1795-1899. Special Series 16. The Postal History Society, 1963.

- Tabeart, Colin. Admiralty Mediterranean Steam Packets 1830 to 1857. Limassol, Cyprus: James Bendon Ltd., 2002.

- ———. United Kingdom Letter Rates Inland and Overseas 1635 to 1900. 2nd ed. Bradford, UK: HH Sales Limited, 2003.

- Clause VII of the 1795 act read: “…That, from and after the passing of this Act, no single Letter sent by the Post from any Non-commissioned Officer, Seaman, or Private, employed in his Majesty’s Navy, Army, Militia, Fencible Regiments, Artillery, or Marines, shall, with such Non-commissioned Officer, Seaman, or Private respectively, shall be employed on his Majesty’s Service, and not otherwise, be charged and chargeable, by virtue of any Act of Parliament now in force, with the higher Rate of Postage than the Sum of one Penny for the Conveyance of each such Letter; such Rate of Postage of one Penny for each such Letter to be paid at the Time of putting the same into the Post Office of the Town or Place from whence such Letter is intended to be sent by the Post…”

Further, clause VIII said: “…That, from and after the passing of this Act, no single Letter sent by the Post, directed to any Non-commissioned Officer, Seaman, or Private, employed in his Majesty’s Navy, Army, Militia, Fencible Regiments, Artillery, or Marines, upon his own private Concerns only, whilst such respective Non-commissioned Officer, Seaman, or Private shall be employed on his Majesty’s Service, and not otherwise, shall be charged or chargeable by virtue of any Act of Parliament now in force, with an higher Rate of Postage than the Sum of one Penny for each such Letter; which Sum of one Penny shall be paid at the Time of the Delivery thereof…“ ↩︎ - Clause XXV of the 1819 act read:

…Seamen in the Navy, whilst actually employed in His Majesty’s Service in The East Indies, and to Non Commissioned Officers in His Majesty’s Army, whilst actually employed in His Majesty’s Service in The East Indies, and also to the Seamen and Non Commissioned Officers in the Army actually employed in the Service of the East India Company… ↩︎ - This act was mainly on punishing mutiny and desertion of officers and soldiers in the services of the EIC. After 52 clauses dealing with transgressions, the 53rd contained the relevant provisions that we are interested in! ↩︎

- That’s why soldiers’ letters from India were almost always sent via the long sea route through Falmouth (Southampton from September 1843 onwards) and not via the quicker route via Marseilles. ↩︎

- While it is thought that these are the only four soldiers’ letters from India to US in existence, my friend, Martin Hosselmann, informs me that some more exist out there. ↩︎

- At the Bombay GPO, there existed the small oval INDIA handstamp and a big/fat INDIA too. They were used concurrently from 1837 to 1856-57. The necessity for using both, when either one would have sufficed, for almost two decades is not known with certainity. ↩︎

- All soldiers’ letters to US would be sent by the British PO through a British packet and not an American packet. Else US would raise a debit of 8d or 16c per single letter being transatlantic sea postage under the 1848 Anglo-US postal convention. ↩︎

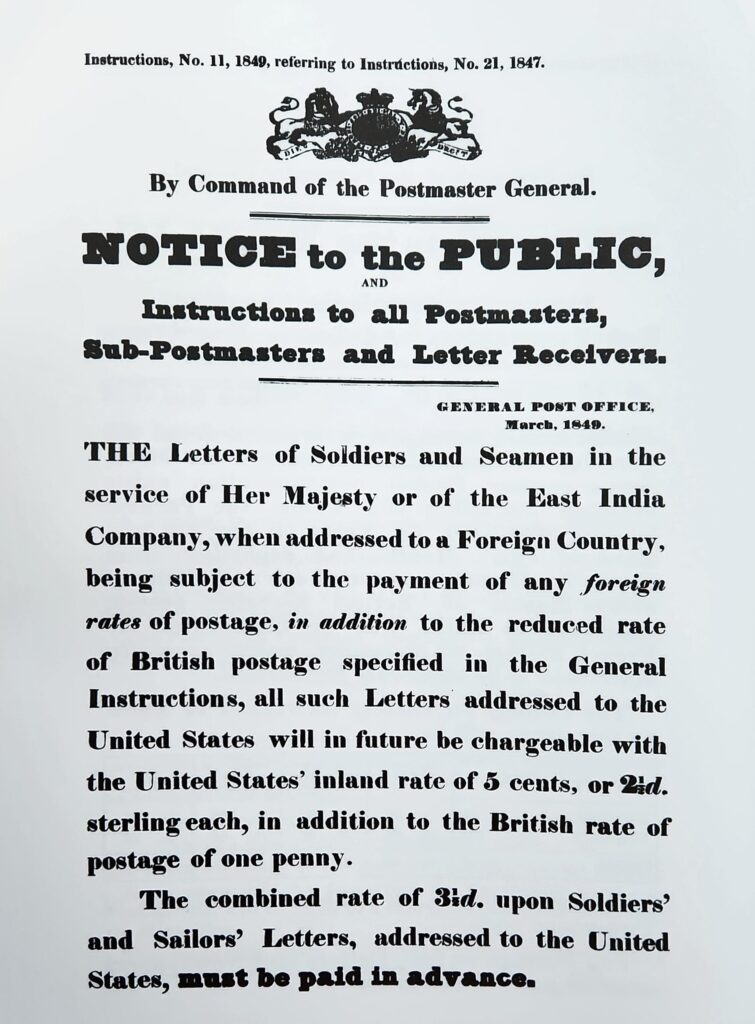

- In late 1848, Great Britain and US signed a postal convention which came into effect from 15 February 1849. This convention provided for US inland postage of 5c. ↩︎