Much has been written on the two voyages of that pioneering steamship Forbes from Calcutta (see references). The first failed to go beyond Madras while by reaching Suez, the second trip proved to be a success.

In this article, I will focus on letters from central and south India which were dispatched to Madras with the intention of catching the steamer on her first voyage. However, due to her breakdown these letters never did get on board.

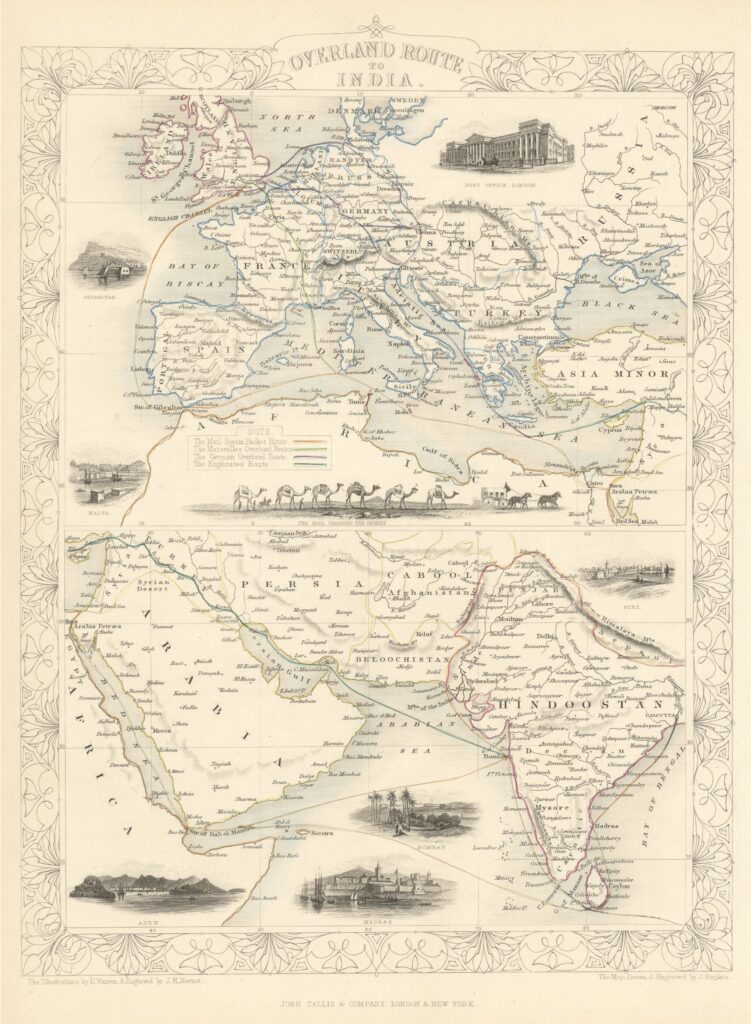

The dawn of the 1830s saw steamships starting to be used for carrying Indian mails. In the first few years until mid-1837, steamers made sporadic trips (once or twice a year!) to either the Red Sea or, much less frequently, the Persian Gulf. Letters would be taken overland across Egypt to Alexandria or overland across West Asia and then by sea to the same port. Finally, another steamer would proceed from Alexandria to Falmouth in Great Britain (Figure 1).1

The first steamer to sail from India for Suez in the Red Sea was the East India Company’s Hugh Lindsay. On her first voyage, she left Bombay on 20 March 1830. Between 1830 and 1833 she made four trips, each trip contributing to “pulling the little cruiser to pieces”. Since the Company’s Court of Directors showed little interest in furthering steam communications between India and Britain, a ‘Steam Committee’ comprising of private individuals was formed in Bombay in 1833 to make arrangements for establishing a more frequent steam line between Bombay and Suez.

Now, a similar Steam Committee had been formed at Calcutta as far back as 1823. However, their various efforts had not borne fruit. A new Committee was formed in 1833 and a steam fund started; but with the express condition that the monies so raised should never be joined with that of the Bombay fund! After all, the great cities of Bombay and Calcutta, situated on opposite sides of the Indian subcontinent, were great rivals too.

Lord William Bentinck (Figure 2), Governor of Bengal (1828-33) and Governor-General of India (1833-35), was very sympathetic towards the cause. In late 1833, he suggested that a steamer be purchased or leased by the Supreme Government of India and operated from Calcutta to Suez by the Bengal Committee. The Forbes was consequently chartered from the owners for a maximum of three voyages to Suez at the rate of 4,000 rupees per month, the expense to be borne by the Bengal Government. The Steam Committee assumed the cost of the necessary fuel depots, having already raised about 130,000 rupees for the steam fund.

Forbes Sails but Fails!

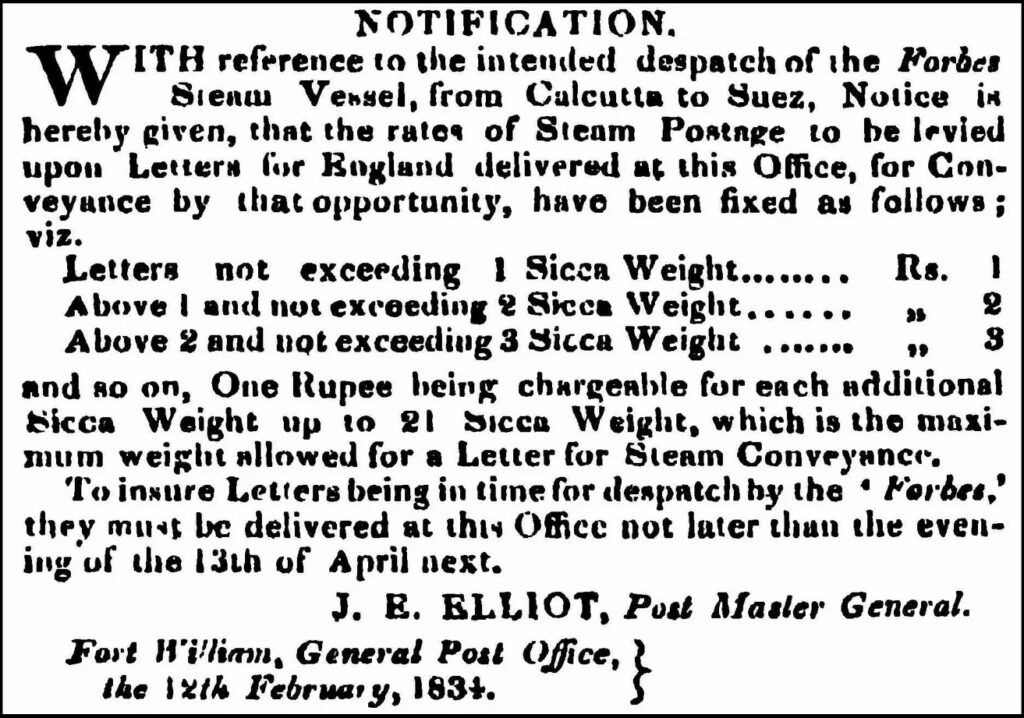

On 12 February 1834, John Edmond Elliot, the Postmaster General of Calcutta GPO, issued a notice informing the public of the “intended despatch of the Forbes Steam Vessel, from Calcutta to Suez” sometime in mid-April (Figure 3).

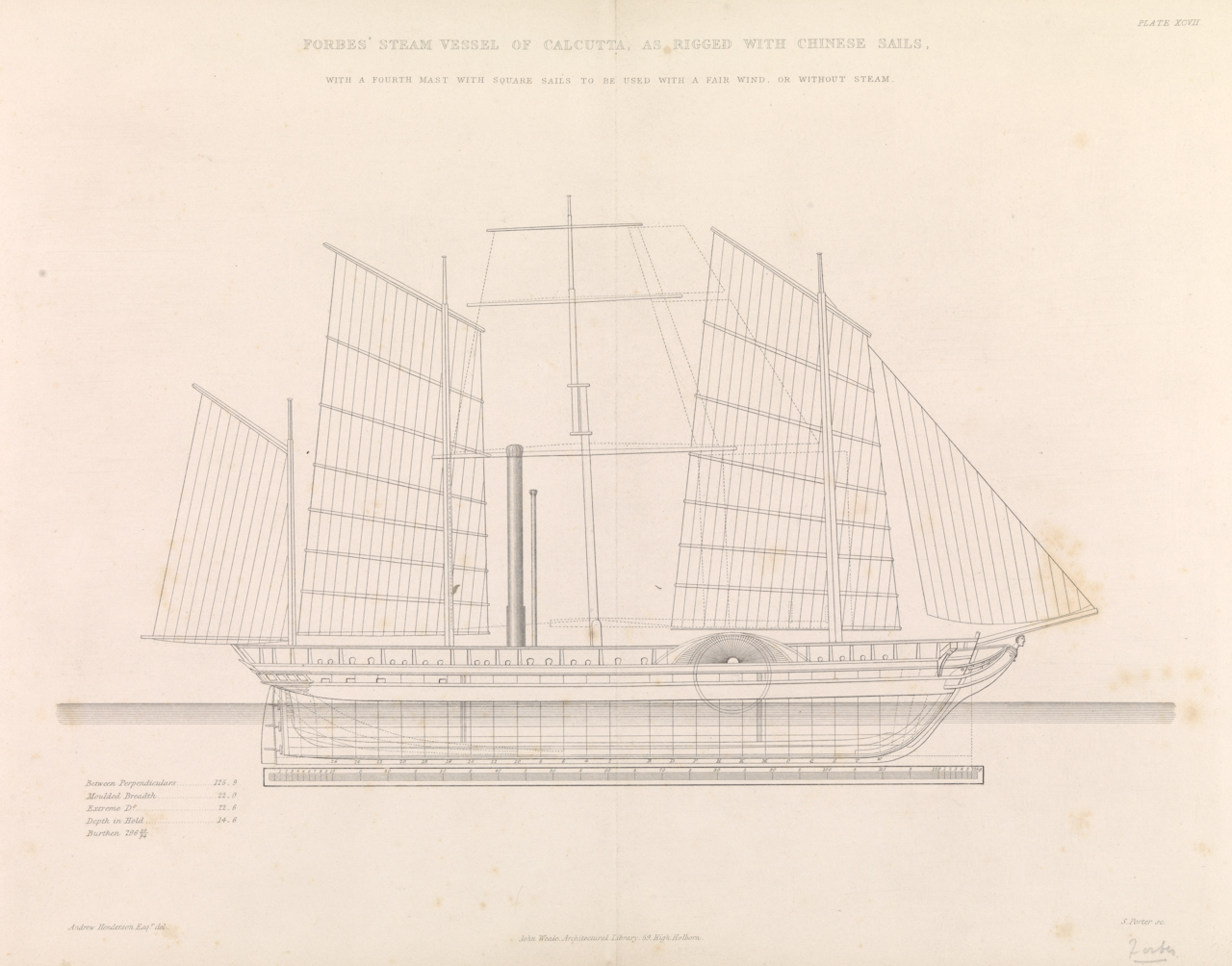

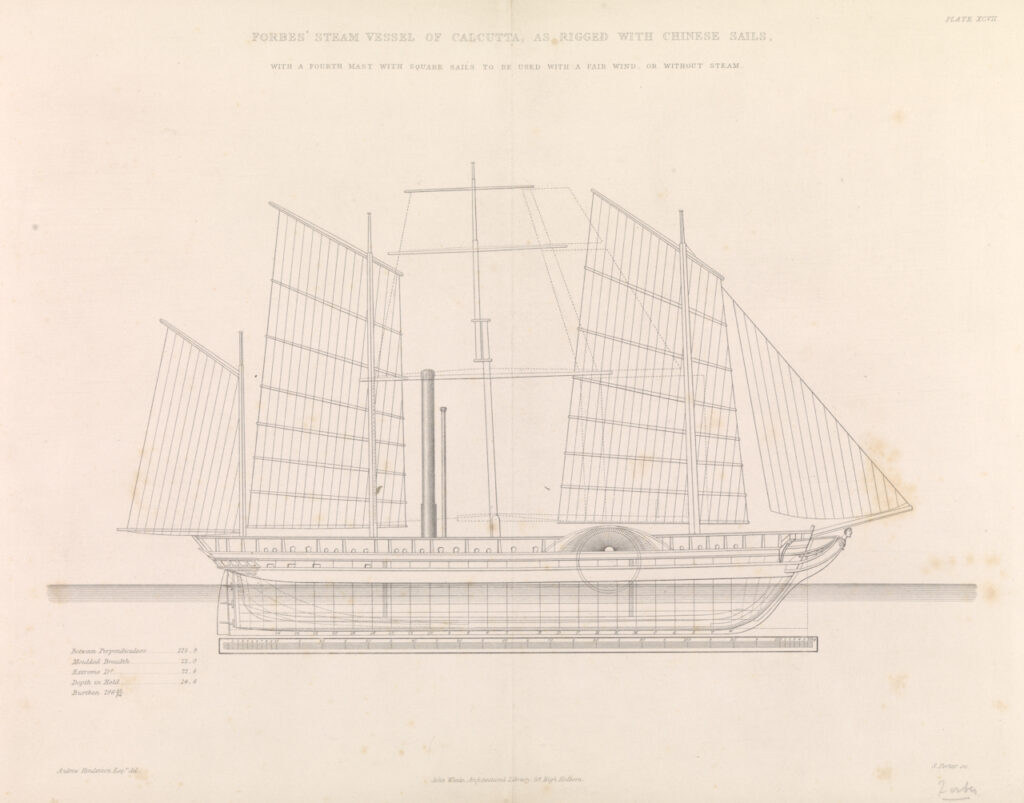

Before going forward, a brief note on the steamer Forbes (Figure 4). Launched in 1829, she was a teak vessel constructed at the Howrah Dock Co. at Sulkea (opposite Calcutta) for Mackintosh & Co. It had cost 310,000 rupees to make her. Of builder’s measurement 161 tons, she had two Bolton & Watt engines that generated a total of 120 horsepower.

Forbes left Calcutta on 14 April 1834 with mails and three passengers each of whom had paid 1,000 rupees (£100). On 23 April she reached Madras, at least a couple of days late. There had been trouble with her boiler en route. Engineers at Madras tried but could not repair her and the voyage had to be abandoned.

On 1 May, the steamer left Madras and limped back to Calcutta under sail.

Over the next few days, the Bombay press had a field day directing much mirth and mockery towards the Calcuttans!

Calcutta and Bombay Letters

About 4,000 letters had been put onboard the Forbes at Calcutta (Bombay Gazette of 14 May 1834, p.228). After it became apparent that the Forbes could not continue on to Suez, the Calcutta letters were offloaded at Madras and sent to Bombay. So were those Bombay letters which had been sent by Express to Madras to catch the Forbes.2

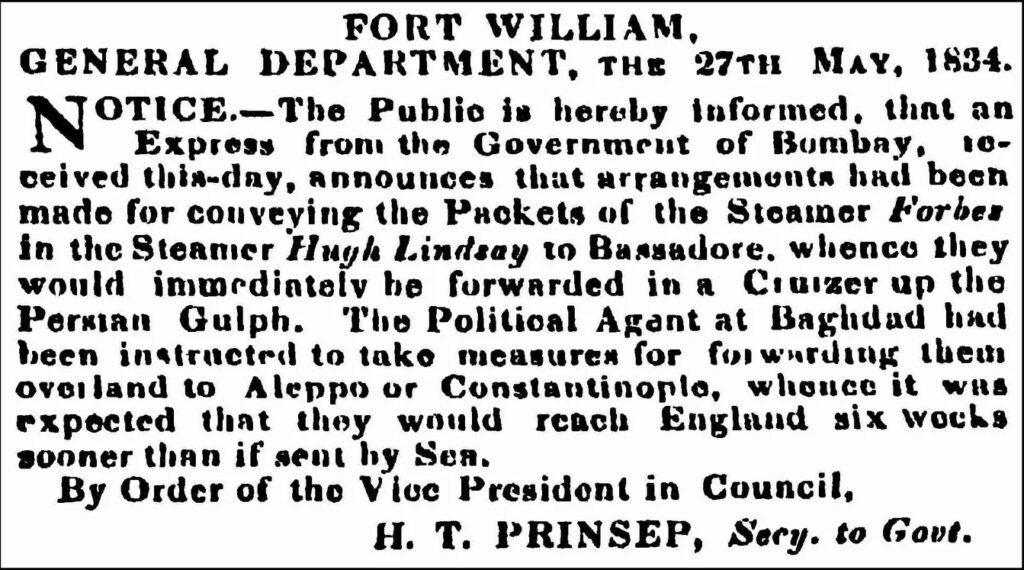

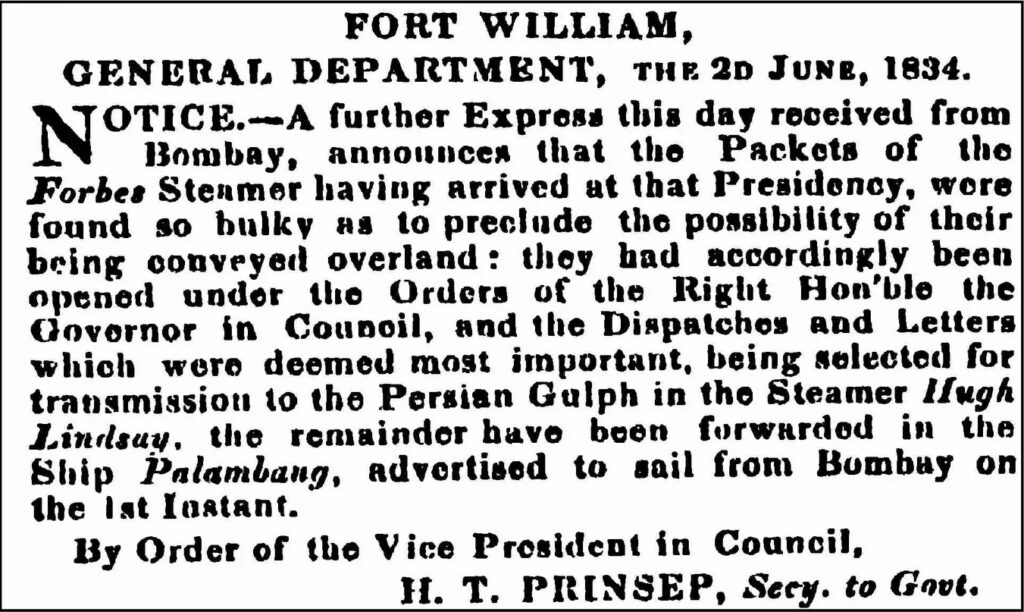

Initially it was thought that these would be carried by the Hugh Lindsay to the Persian Gulf (Figure 5) so that they would reach six weeks sooner than if sent around the Cape.

However, when the packets arrived at Bombay, they were “found to be so bulky as to preclude the possibility of their being conveyed overland”. Almost all were put on board the ship Palamban (spelt Palambang in the notice) to be carried around the Cape (Figure 6).

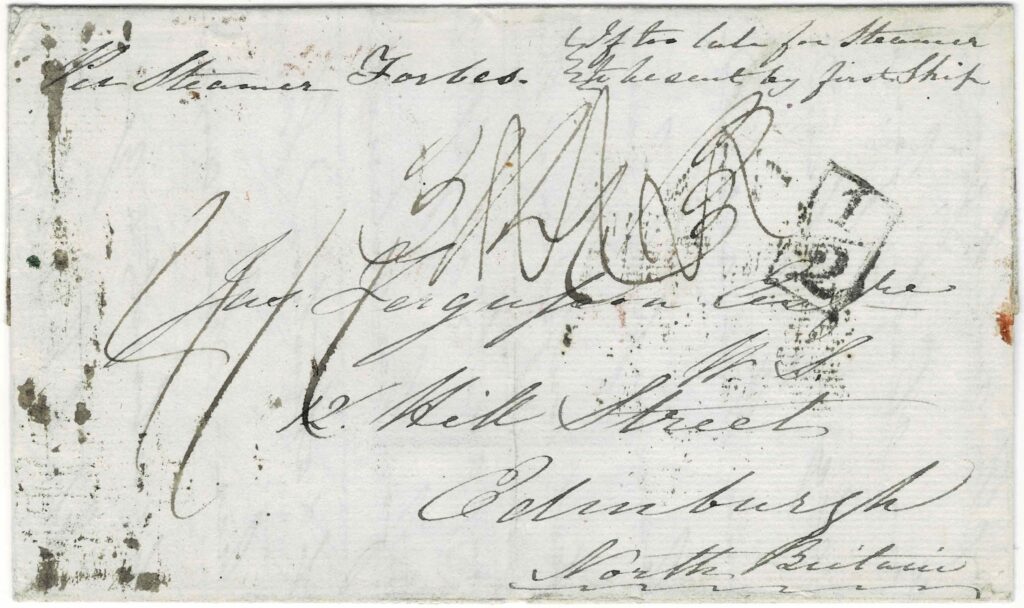

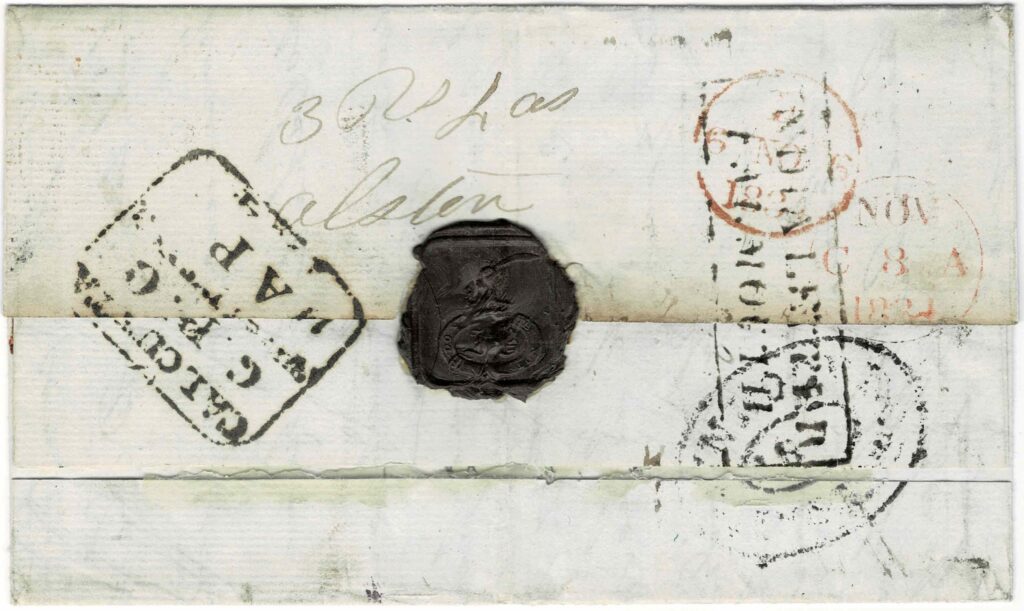

Just a handful of letters (I have records of three), are known which were carried on the first failed voyage. One such is illustrated as Figure 7. It was written on 6 April 1834 by Lieutenant William Alston of the 68th Regiment Bengal Native Infantry. Initially containing three sheets of paper, only a part survives. It says (emphasis mine):

I have been anxiously expecting … from you, since the receipts of the … returning intelligence of my … Father’s death, for which we … great degree prepared – however … since then arrived – so I should … on business so far, as to say … perfect confidence … that you … anything as its ought to be … best for her interest … I send this by the steamer…

Endorsed ‘Per Steamer Forbes’ (as also ‘If too late for Steamer / to be sent by first Ship’) the letter was posted in the small town of Mynpooree (i.e. Mainpuri in the state of Uttar Pradesh). The Lieutenant paid a hefty 3 rupees 4 annas (see rear ‘3 Rs 4 as’) i.e.

- 1r4a Bengal Presidency inland postage from Mynpoorie to Calcutta (600-800 miles) on double letters weighing 1-2 tolas (Rate effective 11.04.1832 to 30.09.1837) plus

- 2r steam postage to Suez on letters weighing 1-2 tolas (Rate effective 31.12.1833 to 05.11.1835)

(16 annas = 1 Rupee; 12 pence = 1 shilling; 1 anna = 1½ pence or 1 Rupee = 2 shillings)

When the letter reached GB, it was treated as a ship letter and the ‘INDIA LETTER / FALMOUTH’ impressed on the rear. On arrival in Edinburgh, the recipient was charged 4 shillings 1 penny (see ‘4/1’ applied on front) i.e.

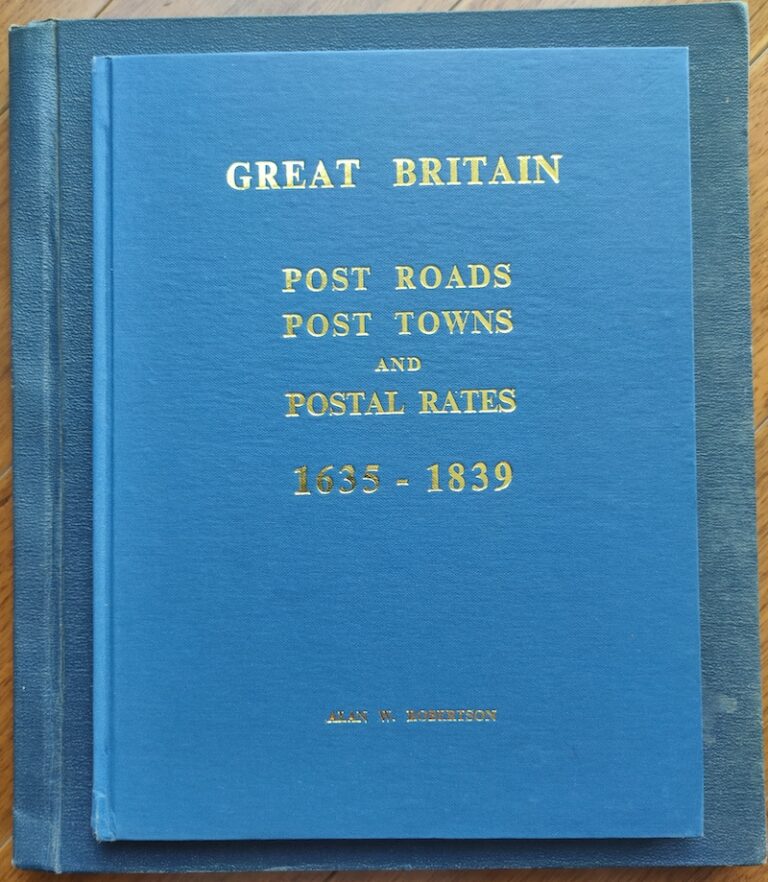

- 3s9d inland postage on treble letters containing three sheets up to 1 oz from Falmouth to London to Edinburgh (600-700 miles) (Rate effective 09.07.1812 to 04.12.1839) plus

- 4d India Letter rate per item up to 3 oz (Rate effective 14.07.1819 to 09.01.1840)

Further, Scottish Additional Half Penny Tax (see boxed ‘½’), which was payable on letters of any size, was also recovered from the recipient (Rate effective 09.06.1813 to 04.12.1839).

Forwarded by Overland Route

Some letters from the failed voyage were subsequently sent overland from Bombay.

Under orders of the Governor in Council, the returned packets were opened and those letters deemed most important i.e. government dispatches were selected to be sent on the Hugh Lindsay to the Persian Gulf (Figure 5).

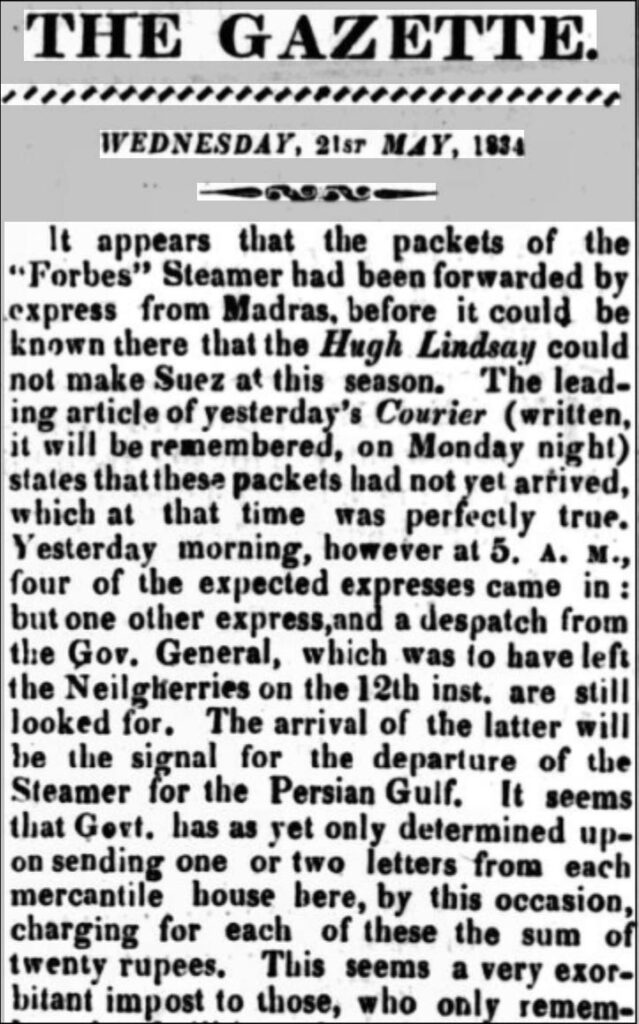

In addition, Bombay merchants who could afford to pay the mind boggling sum of 20 rupees (equivalent to £2) per letter could make use of this opportunity too. A report in the Bombay Gazette gives more details (Figure 8).

We do not know how many of the Forbes’ letters were sent overland. I have personally never seen one.

Letters to Madras GPO

Now we come to the crux of this article.

What happened to letters which were dispatched from various towns in Central and South India to Madras with the intention of putting them on the Forbes?

When the Forbes had docked at Madras, there were only about 1,000 letters awaiting her. News of her arrival spread and the number quickly increased to 3,000 (Bombay Gazette of 14 May 1834, p.228).

On 1 May i.e. the same day that the Forbes left Madras, the Postmaster General of Madras GPO, Nathaniel Webb, issued the following notice:

The voyage of the Steamer Forbes to Suez, having been frustrated owing the defective state of the boiler…Notice is hereby given that all letters received at this Office, marked per that vessel…will be forwarded by the first opportunity for England, but the Steam Postage on them will be refunded on an official application being made to the Post Master General, enclosing or producing the stamped receipt granted by this Office.

The 3,000-odd letters were forwarded by the ship Alfred to England.

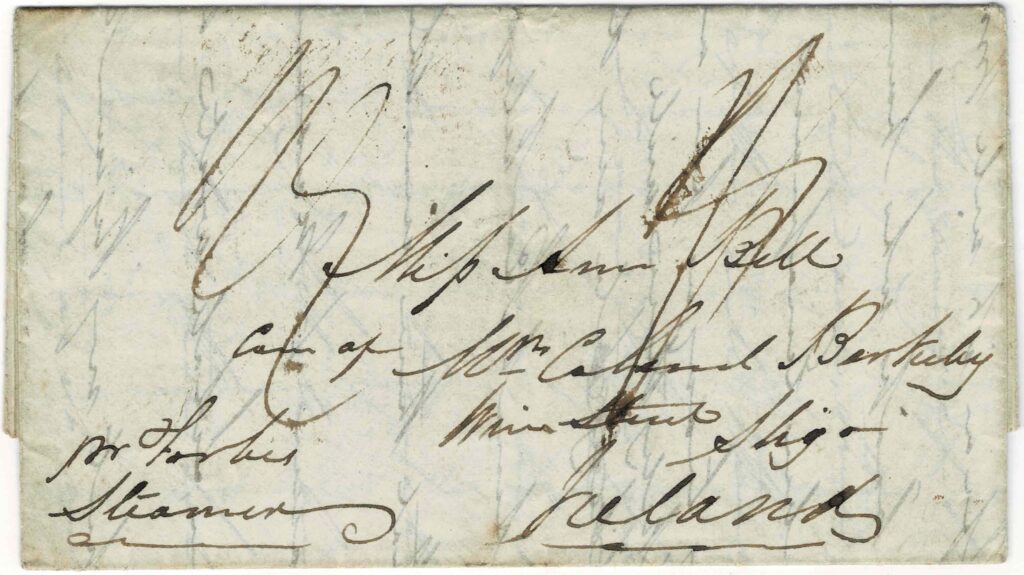

Figure 9 shows one example datelined 13 April 1834 and posted from the small south Indian town of Samulcottah (Samalkota in Andhra Pradesh). The sender was Lieutenant-Colonel John Bell of the 47th Madras Native Infantry; the regiment was was based at Samulcottah at this time. The recipient was his daughter Ann Bell in Sligo, Ireland. Among other things, it says:

…I shall send this on a steamer expected at Madras on the 18th. Inst. and hope it will be with you in a little better than two months from this time…I have several letters to write by this opportunity…

…They may look and find letters from me by the way first ship after this, it is too expensive to send all my letters by steamer and I think not what may be charged on them at home, nothing is yet settled, but what we pay in this country…

Also endorsed ‘pr Forbes / Steamer’, the sender paid a total of 1 rupee 9 annas postage (see rear) i.e.

- 9a Madras Presidency inland postage on letters from Samulcottah to Madras (350-400 miles) weighing 1 tola (Rate effective 01.04.1834 to 30.09.1837) plus

- 1r steam postage on letters weighing 1 tola (Rate effective 31.12.1833 to 05.11.1835)

Note that while inland postage varied in the Presidencies of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay, steam postage was the same across the three.

The letter did not travel on the Forbes but on the sailing ship Alfred. While the sender was entitled to a refund of steam postage. we do not know whether he applied for and got it.

The addressee paid 1 shilling 9 pence on receipt. The breakup of this sum is as follows:

- 1s2d inland postage on single letters containing one sheet up to 1 oz rate from Brighton to London, London to Holyhead, and from Dublin to Sligo (400-500 miles) (Rate effective 09.07.1812 to 04.12.1839) plus

- 4d India Letter rate per item up to 3 oz (Rate effective 14.07.1819 to 09.01.1840) plus

- 2d packet postage on single letters containing one sheet up to 1 oz across the Irish Sea from Holyhead to Dublin (Rate effective 05.1821 to 04.07.1827) plus

- 1d Menai Bridge charge on single letters containing one sheet up to 1 oz (Rate effective 15.07.1819 to 04.12.1839)3

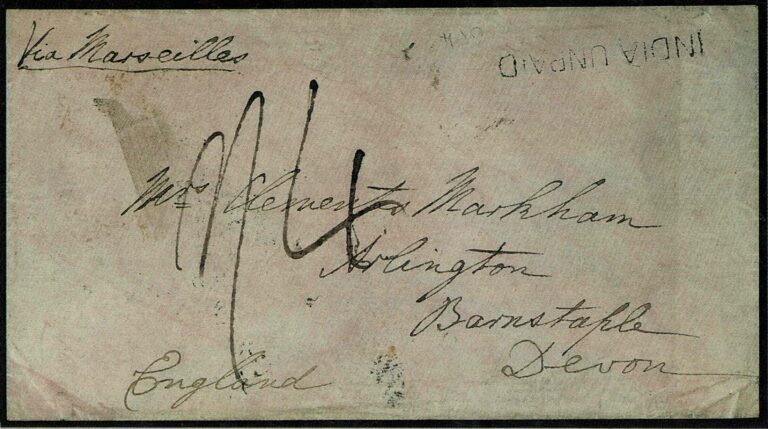

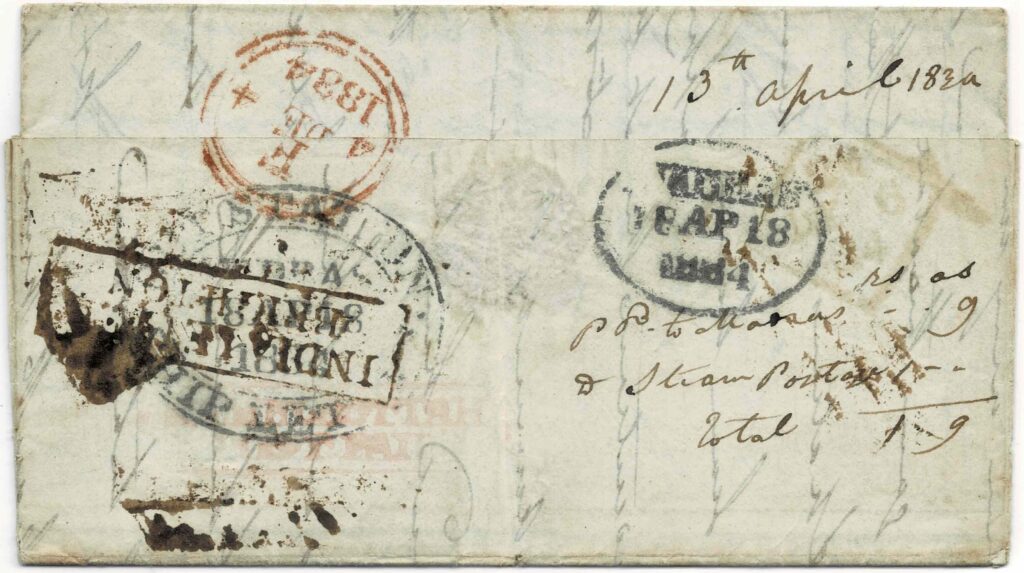

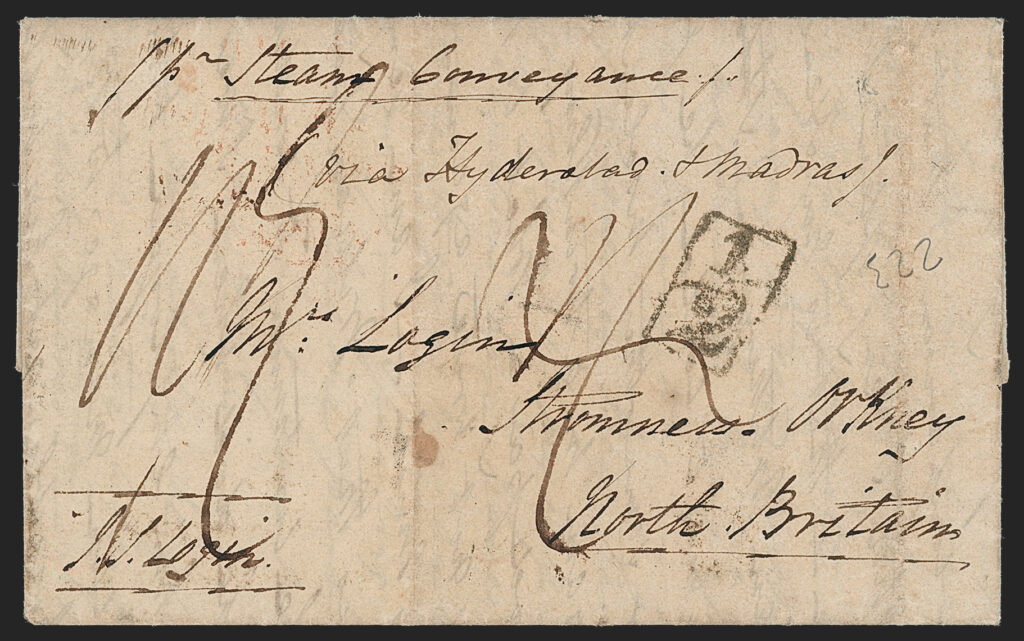

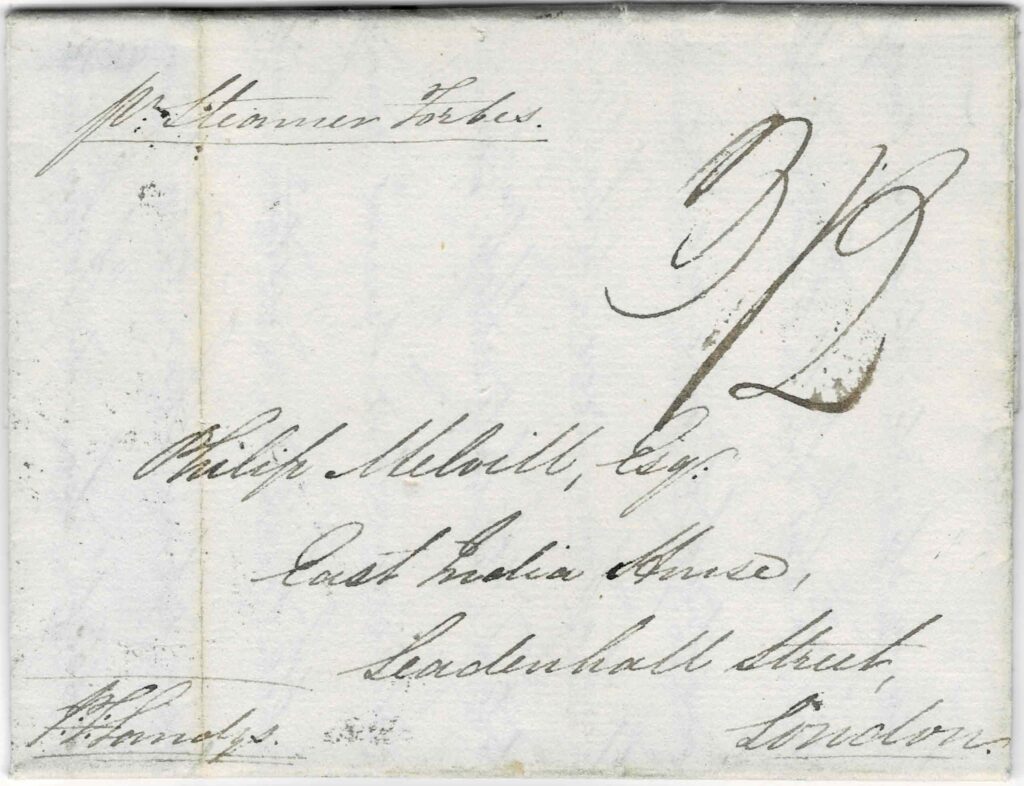

Another similar letter is presented as Figure 10. Written from Hingolee (Hingoli in Maharashtra) on 13 April, it was sent to Madras via Hyderabad.

The sender was an Assistant Surgeon in the Nizam of Hyderabad’s army, John Spencer Login.4 The recipient was his mother.

Do not be surprised at having to pay a very high postage for this letter – as I intend to avail myself of the first opportunity by Steam Conveyance via the Red Sea and Egypt – in hope that this may reach you in little more than two months! – I am wrong in saying that this is the first opportunity by Steam since there have been sevl. [several] before, from Bombay, but it is the first under the new and I hope permant. [permanent] arrangemt. [arrangement] as this has to reach the vessel at Madras from which I am dist. 10 days Dâk – it will probably be a week later than if the opportunity had occurred via Bombay – from it I am only dist. 360 Miles…This is my third letter to you since I came on this side of India – but it may perhaps reach you before the first…mention what the postage of this is…Let me know particularly on what date this reaches you…

Endorsed ‘pr Steam Conveyance’, the sender paid a total postage of 1 rupee 10 annas (see rear) i.e.

- 10a Bengal Presidency inland postage5 on letters from Hingolee to Madras (600-800 miles) weighing 1 tola (Rate effective 11.04.1832 to 30.09.1837) plus

- 1r steam postage on letters weighing 1 tola (Rate effective 31.12.1833 to 05.11.1835)

Again, we will never know whether Login applied for and got his refund of the steam postage.

Mrs. Login was charged 1 shilling 9 pence (see ‘1/9’ applied on front) which can be explained as:

- 1s5d inland postage on single letters containing one sheet up to 1 oz from Brighton to London to Stromness, Orkney (700-800 miles) (Rate effective 09.07.1812 to 04.12.1839) plus

- 4d India Letter rate per item up to 3 oz (Rate effective 14.07.1819 to 09.01.1840)

Similar to a letter we saw earlier, Scottish Additional Half Penny Tax was also recovered from the recipient.

First Successful (Second) Voyage of Forbes

The Forbes did manage to complete a trip a few months later when she sailed out of Calcutta on 4 September 1834 reaching Suez on 16 November.

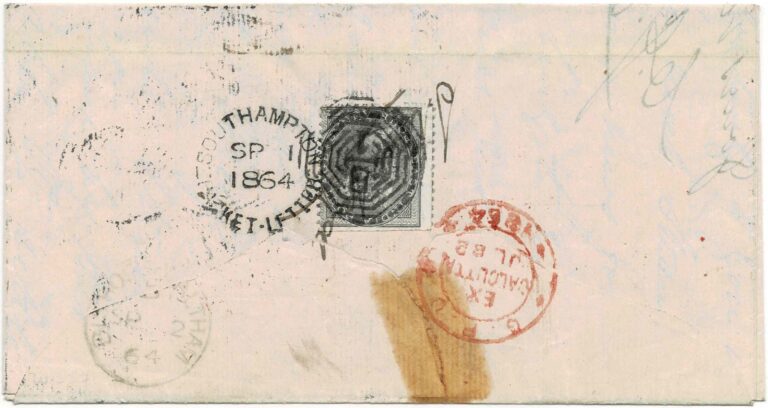

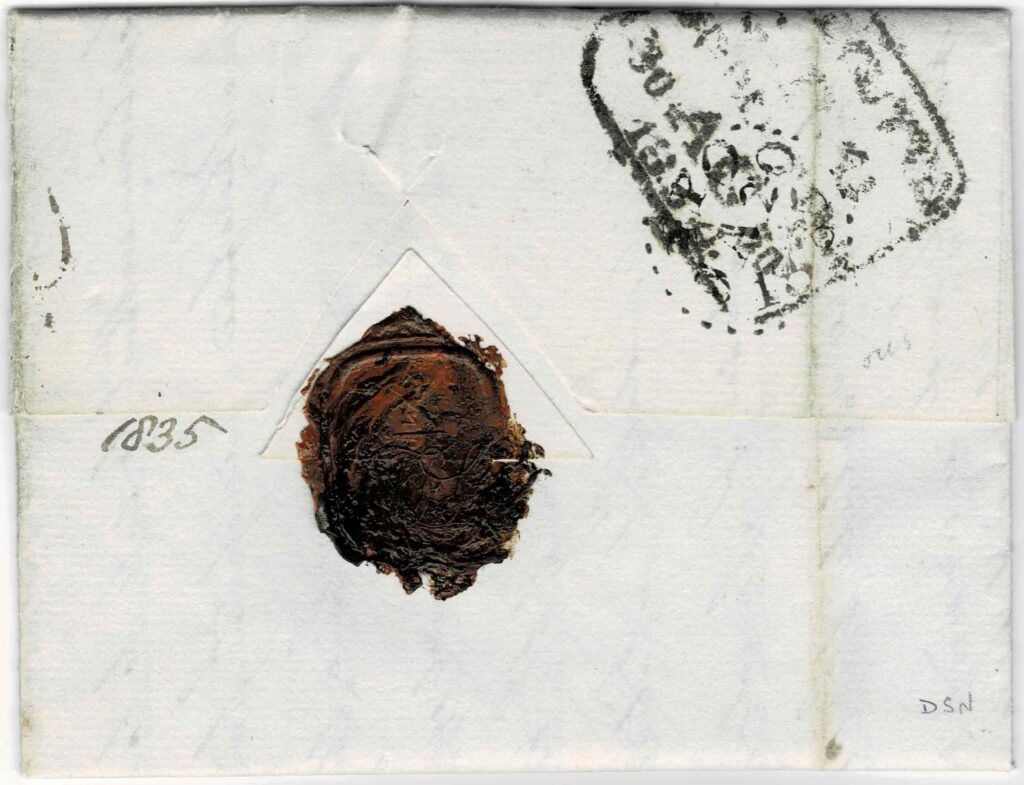

This sailing may be termed as either the ‘Second Voyage of the Steamer Forbes’ or ‘First Successful Voyage of Forbes’. Only a few letters, sent from both Bengal and Madras Presidencies, are known (my records have six). One such is illustrated as Figure 11.

Written on 29 August 1834 by Thomas Sandys of the East India Company’s maritime service to Philip Melvill Melvill at the East India House in London, it reads:

I have your several letters before me, two dated the 27th of Decr. last, and the other the 13th of February following. The two first giving cover to the original and duplicate Protest of non-payment of the Bill for £345 Stg. and the third, to Mr. W. Sandys’ letter on the subject of the dividend paying by the acceptors of that Bill. As this goes by the steamer Forbes to Suez, I must be brief…

No inland postage was applicable since the letter was put into the Calcutta GPO. While the letter is endorsed ‘pr Steamer Forbes’, the steam postage paid is not noted. But undoubtedly, the sender would have had to pay 1 rupee per tola.

On arrival, the letter was treated as a packet and not a ship letter. The addressee shelled out 3 shillings 2 pence:

- 2s3d packet rate on single letters containing one sheet up to 1 oz from GB to Alexandria (Rate effective 26.01.1835 to 17.08.1837) plus

- 11d (1s less 1d)6 inland postage on single letters containing one sheet up to 1 oz from London to Falmouth (230-300 miles) (Rate effective 09.07.1812 to 04.12.1839)

Seven Year Hiatus

The enormous expenses incurred on her two sailings so put off the powers to be that the third trip of the Forbes scheduled for sometime in 1835 was scrapped. In addition, the 74 day voyage from Calcutta to Suez, under a combination of steam and sail, showed how inept small steam vessels were in crossing the seas.

The Forbes went back to towing sailing vessels up and down the river Hoogly!

No further experiments were conducted at Calcutta for more than seven years until January 1842 when the steamer India left on the first of her four (non-contract) voyages to Suez.

References

- Blair, C. N. M. “More News on the Forbes’ First Voyage.” India Post, 10 no. 1 whole no. 47 (January-March 1976).

- ———. “More News on the Forbes’ Second Voyage.” India Post, 10 no. 2 whole number 48 (April-June 1976).

- Giles, D[erek]. Hammond. Catalogue of the Handstruck Postage Stamps of India. Christie’s Robson Lowe, 1989.

- (Heddergott, Jochen). Classic India & Scinde 1600-1858: The Jochen Heddergott Collection. XX. Edition D’OR. Corinphila Auktionen AG, 2010.

- Hoskins, Halford Lancaster. British Routes to India. Longmans, Green and Co., 1928.

- Phipps, John. A Collection of Papers, relative to Ship Building in India with Descriptions of the Various Indian Woods Employed Therein, their Qualities, Uses, and Value…Scott and Co., 1840.

- Robinson, David. For the Port & Carriage of Letters: A Practical Guide to the Inland and Foreign Postage Rates of the British Isles 1570 to 1840. The Author, 1990.

End Notes

- Sometimes Persian Gulf letters would not go via Alexandria but travel overland across West Asia and Europe. ↩︎

- In a letter to the editor of the Bombay Gazette, ‘Dick – A Northward Boy’ complained that the Bombay Postmaster General had issued a notice in the Government Gazette of 3 April 1834 mentioning that an Express would be dispatched from Bombay on 11 April and that it was too short a notice for the “Northern Gents.” (Bombay Gazette of 16 April). ↩︎

- Menai Bridge Charge was a means of defraying the expense of construction of this bridges. An extra 1d single, etc. was added to letters to/from Ireland that crossed the bridge on their way to/from Holyhead. Note that this was not a toll on all letters that crossed the bridge; internal British mail from say London to Holyhead did not pay any extra fee. ↩︎

- Login was later Governor of Lahore and being the “most trustworthy man in India” was appointed as the guardian of Maharajah Duleep Singh (son of the great Ranjit Singh) and the Koh-i-Noor diamond. ↩︎

- Even though Hingolee and Hyderabad are physically closer to Madras than Calcutta, their Post Offices came under the auspices of Bengal Presidency at this time. Hence, Bengal Presidency inland rates applied for the carriage to Madras. ↩︎

- The Postage Act, 1812 which increased the inland rates by 1d and the packet rates by 2d did not make both the additional rates applicable when added together. Therefore, the British Post Office abated the inland charge for packet letters via Falmouth by 1d. ↩︎