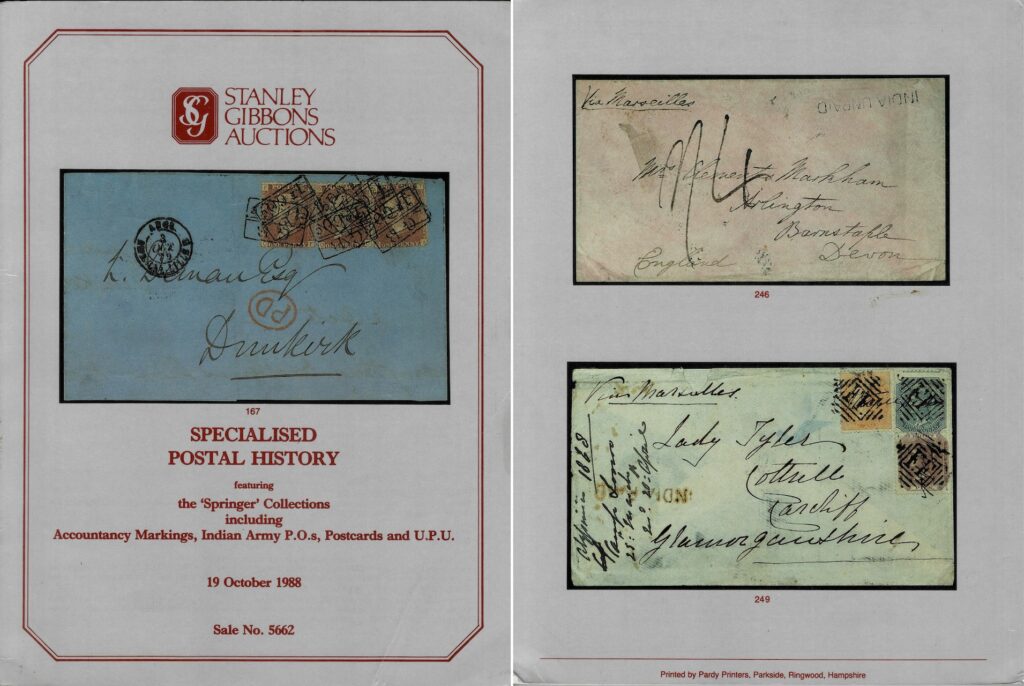

Sometime back, I was browsing an old 1988 Stanley Gibbons auction catalogue featuring the ‘Springer’ Collections (Figure 1).

A claim is made inside:

The lots of the Indian Army P.O. included in this catalogue form probably the most comprehensive study of this service ever formed.

Indeed, it contains many Indian Army postal history items – Field Force P.O. covers from campaigns in the 1880s and 1890s, World War I and II, etc. as also campaign mails including the Persian Field Force, Abyssinian Expedition, and Second Afghan War. It is surely an early sale on this popular subject. Many of the items listed there now form part of various important collections.

The Problem Child

One of the lots in this sale is no. 246. Its description is printed in bold letters, signifying that it consists of a very important item. It reads:

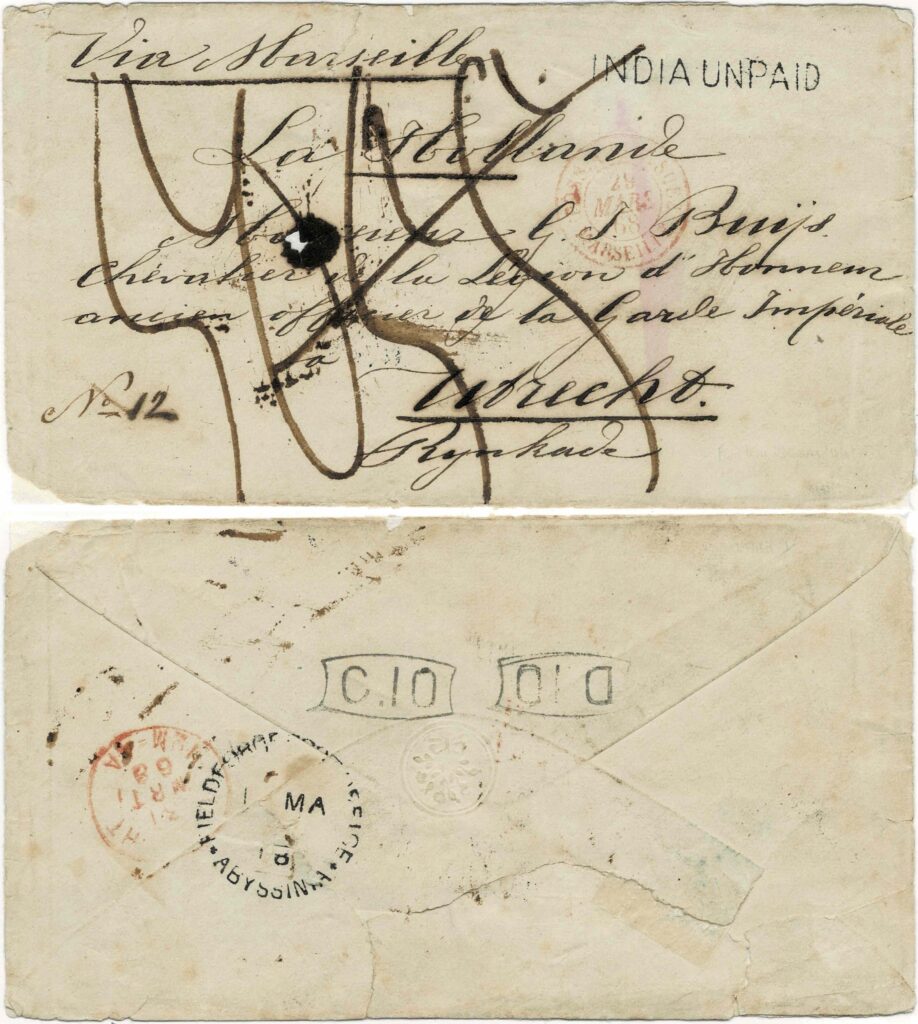

Abyssinian Field Force: 1867 stampless cover to Devon with frameless INDIA UNPAID in black attributed to the Base P.O., rated 1/4d., backstamped ADEN STR. POINT 8 Dec. c.d.s., London c.d.s. in red and Barnstaple arrival, the earliest recorded cover from the base office used before the arrival of F.F. marks…

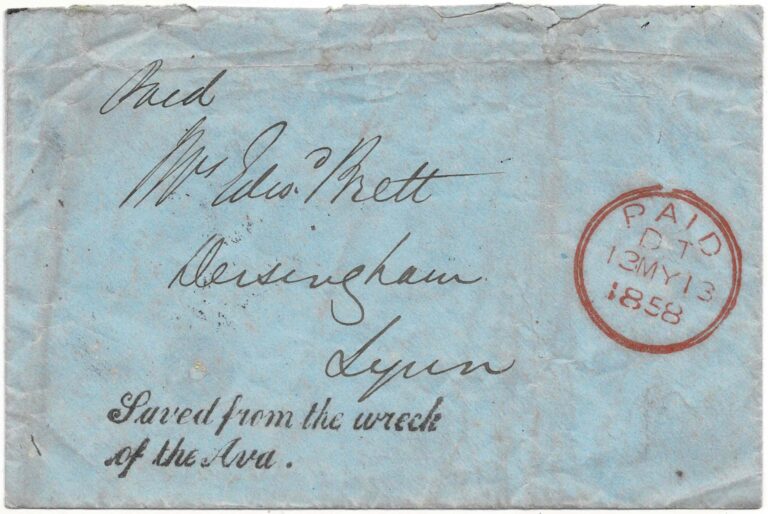

The estimate was a whopping £4,000! A huge number 37 years back. It did not see any bidders though. The cover is illustrated on the back cover and is also shown in Figure 2.

The question that this article proposes to answer: Is this cover from the Abyssinian Expedition of 1867-68?

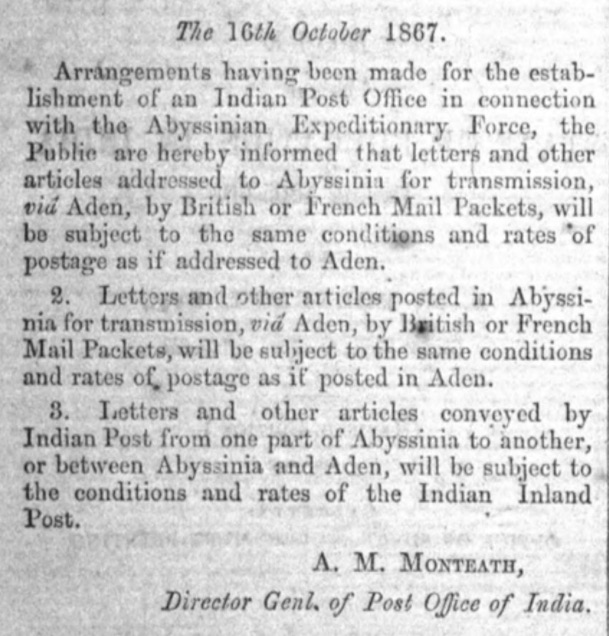

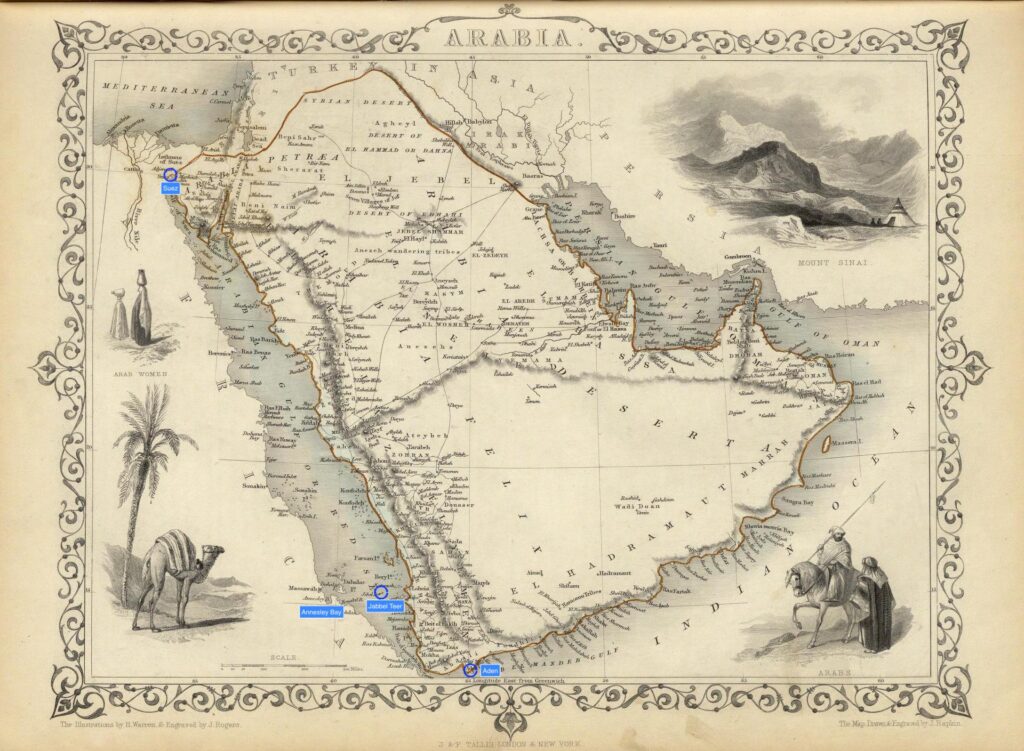

The Expedition is one of my favourite collecting sidelines. I have written an article on it which contains much background information. So, just two lines on the postal arrangements associated with this Expedition will suffice here. First, it was the Indian Post Office which was responsible for all postal matters. Second, rates of postage applied from (and to) the Expedition were the same as rates from/to India (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Indian Post Office Notice dated 16 October 1867 on the Expedition

Clements Markham

Let us look at the cover carefully. It is addressed to one Mrs. Clements Markham. The ‘Mrs.’ implies that she was either someone’s wife or mother. Generally, husbands and sons serving in far-flung lands would write such.

Given my interest, I have read a bit about the Expedition. I immediately knew that this cover was sent by Mr. Clements Markham who had accompanied the Expedition as a geographer; so, a letter from a husband to his wife.

What if I did not have this information in my head? Well, I would have had to do some digging. Sometimes I would find the answer in a jiffy. And sometimes, it would take hours or even days.

Now, who was Markham?

Sir Clements Robert Markham (1830-1916) (Figure 4) was an English geographer, explorer, and writer.

Figure 4. Clements Robert Markham by Camille Silvy, 4 July 1862. Copyright: National Portrait Gallery.

He was born in Yorkshire in a respected and affluent family which descended from William Markham, former Archbishop of York, 1777-1807, and royal tutor.

A chance meeting with Rear-Admiral Sir George Seymour, Lord of the Admiralty saw him enroll as a naval cadet in 1844. He sailed out of Portsmouth on HMS Collingwood, Seymour’s flagship, on his 14th birthday for a four-year voyage to the Pacific.

Returning in mid-1848, Markham realised he was no longer interested in a naval career. He now desired to be an explorer and a geographer. Nevertheless, he stayed on. In May 1850, using his family’s connections, he secured a place on one of the four ships sailing out to search for the lost Arctic expedition of Sir John Franklin. This time, when he returned home, he followed his heart and resigned from the navy sometime in end-1851. In hindsight, this was the correct decision since plenty of travel and adventures around the world followed.

In 1857, Markham joined the forerunner to the India Office and was employed there until he retired in 1877.

In his later years, he was Honorary Secretary to the Royal Geographical Society between 1863 and 1888 and its President between 1893 and 1905 (Figure 5). In the latter capacity, he was mainly responsible for organising the British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1904.

Markham wrote some 50 books in his life and after his retirement from the India Office, his writing was his main source of income.

On 29 January 1916, he was in bed reading a book written in old Portuguese. He took the naked candle too close and set fire to the bedclothes. Overcome, he died the next day.

An Abyssinian Letter?

In 1867, during his time as head of the India Office’s geographical department, Markham was selected to accompany Sir Robert Napier’s punitive military expedition to Abyssinia. Markham was attached to the mission’s headquarters staff with responsibility for survey work. He accompanied the final storming party to Magdala and was one of the first to enter the house of Tewodros II, ruler of Abyssinia, who had committed suicide when it became clear that the British were going to defeat him.

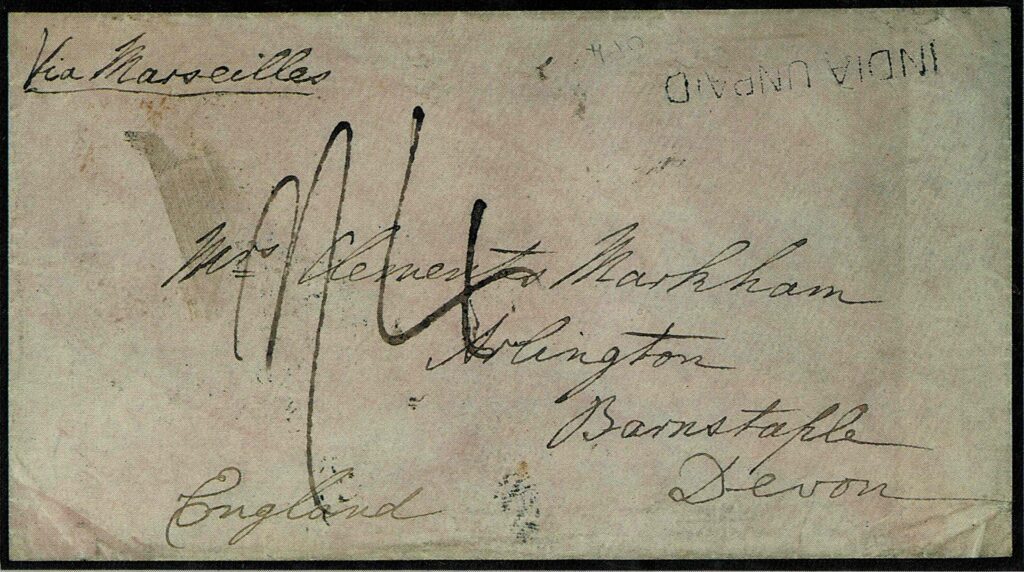

We now come back to the item shown in Figure 2.

The front has an ‘INDIA UNPAID’ and a manuscript ‘1/4’ rating. More on the handstamp a bit later. As far as the rate of 1 shilling 4 pence (i.e. 16 pence) is concerned, it comprises of 10 pence (or 6 annas 8 pies) India-GB rate via Marseilles plus 6 pence (or 4 annas) fine on unpaid letters.

(12 pies comprised 1 anna and 16 annas was 1 Indian rupee. Further, at this time 1 anna was equal to 1.5 pence)

As per the auction catalogue description, the rear (which was not illustrated) has an Aden Steamer Point cds of 8 December 1867. It also has two cds’ applied in Britain – one of London and another of Barnstaple; unfortunately their dates are not known.

Let us get one thing out of the way. Even assuming for a moment that it was written from Abyssinia, this is not the earliest recorded cover from that Expedition. The Aden date of 8 December 1867 implies the letter would have left Abyssinia towards the end of November or beginning of December 1867. There are earlier covers known.

Where was Markham?

To figure whether this cover was indeed sent from Abyssinia, we need to trace Markham’s whereabouts. Where was he then?

We would typically find answers to such questions either in a person’s papers – perhaps a diary that he kept or letters that he wrote to family and friends – or in public sources such as newspaper reports or published books

My first instinct was to search for his biography; surely, there would be one for a person as famous as he was. While Wikipedia and other short entries can easily be found, I wanted something more detailed.

An internet search reveals that Markham’s biography was published in 1917 – The Life of Sir Clements R. Markham written by Albert H. Markham, a cousin. The book is accessible for free on the Internet Archive and Hathi Trust. A perusal shows that, while Markham’s involvement with the Abyssinia Expedition is covered in one chapter, it does not answer the question of his arrival at that place.

Then I searched for books written on the campaign. After going through a few, I came across A History Of The Abyssinian Expedition. It was written by Markham himself and published in 1869. This too is available free on Google Books.

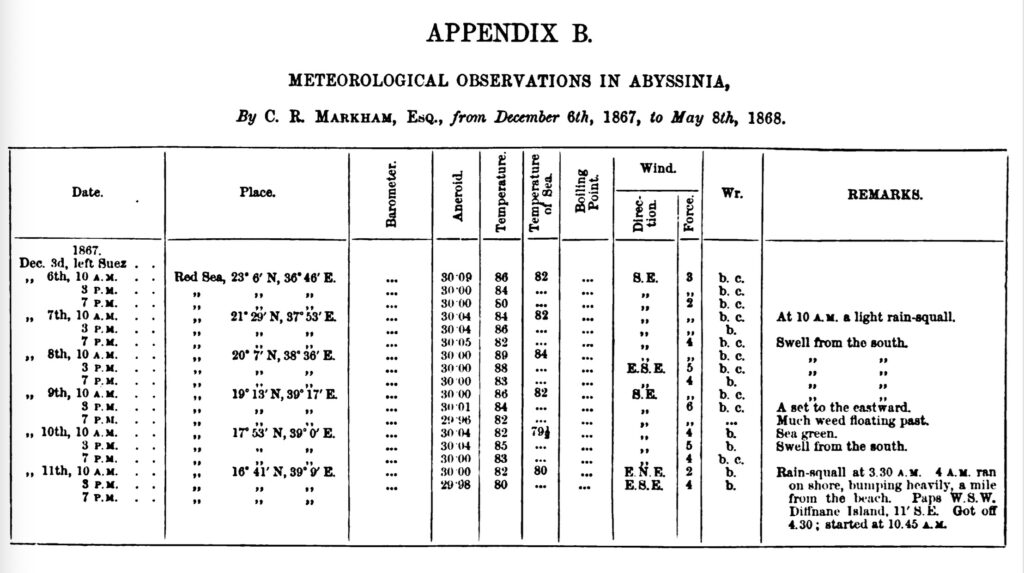

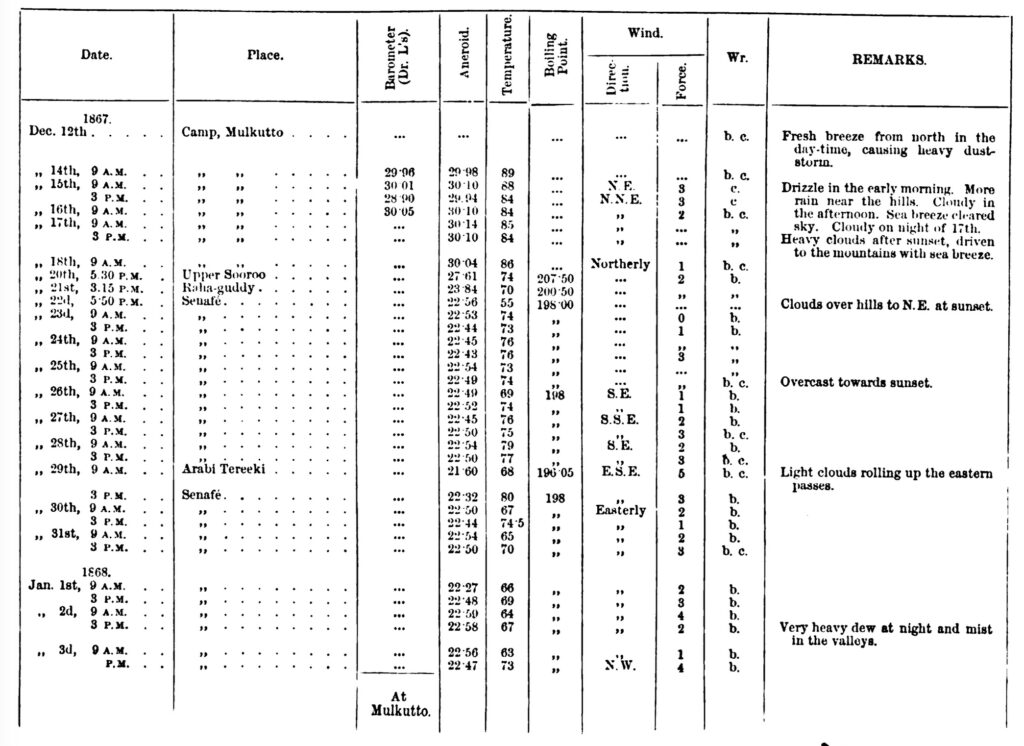

Appendix B (Figure 6) is a table of meteorological observations made by Markham in Abyssinia. It starts from 3 December 1867 when he left Suez. Between that date and 10 December, he was in the Red Sea sailing towards Abyssinia (see Figure 6 to get an idea of the geography). He reached ashore on 11 December (last two lines in the rightmost column says: ‘Got off 4.30; started at 10.45 AM.’) and the first entry on 12 December is from Camp Mulkutto.

(Markham uses ‘Mulkutto’ to refer to the place where the expeditionary forces landed and where the camp was made on the shores of Annesley Bay. It is frequently called ‘Zula’ or ‘Zoulla’ by many including postal historians, a term Markham considers incorrect.)

So, if Markham’s cover has an Aden datestamp of 8 December, it must have been written either at Suez or at sea between Suez and Abyssinia and not at Abyssinia itself. Problem solved!

This piece is not yet done though. A couple more issues still need to be talked about.

‘INDIA UNPAID’

As the handstamp suggests, it was applied on unpaid mails from India sent overseas. Boxed ‘INDIA PAID’ and ‘INDIA UNPAID’ marks are very common. However, from what I have observed, the straight-line ‘INDIA PAID’ and ‘INDIA UNPAID’ was used only in Bombay Postal Circle for a short time in the mid-to-late 1860s; examples are scarce.

So, if this is not an item of Abyssinian Expedition postal history, the corollary is this it is also not the second known cover with the ‘INDIA UNPAID’. The mark was likely applied at Aden, which came under Bombay Circle.

As an aside, I know only one such letter with this mark, which was sent from Abyssinia to Netherlands (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Cover from Abyssinia (1 March 1868) to Utrecht, Netherlands (31 March 1868) via Marseilles. One of two covers from the Expedition to Netherlands and the only one with the ‘INDIA UNPAID’ mark. Ex Paolo Bianchi and Cliff Gregory.

Why are ‘unpaid’ mails from the Expedition so rare?

A few stampless covers do exist but they were not considered unpaid by the Expedition’s Post Office. Some are officials covers sent ‘On Her Majesty’s Service’. Others are personal correspondence sent to Britain which were not franked since Indian stamps were not available in the interiors of the country; hence, no fine was levied on such letters and the recipient only had to pay the prevailing India-GB rate.

Routing via Aden

Why did this letter go to Aden and not Suez? Generally, letters from Abyssinia to Europe, mainly Britain, would be sent to Suez and those to India would be dispatched to Aden for further carriage (in the initial days, by the laborious method of intercepting the mail steamer off the island of Jabbel Teer in the Red Sea). A glance at the above map will make it clear why it was so.

Physical access to this cover (whose whereabouts is unknown) may help in resolving this mystery.

I would love to hear from you. Send your comments and suggestions to abbh@hotmail.com.