A few days back I received a marketing email from the French auction house, BEHR Philatelie. This email, touting their upcoming mail auction on 7 September 2023, contained an image presented as Figure 1.

The image shows an entire letter from lot no. 23. The starting price is an eye-popping €6,750. I am not going to go into the wisdom (or otherwise) of this number. I will, however, say that the item proves that covers with multiple stamps are much more attractive than those with a single franking.

The lot’s description states:

N°1 + 5, Paire du 40c. bistre-jaune + paire du 10c. orange obl. PC 2388 s/lettre frappée du CàD de PAU du 7 juin 1853 à destination de BENGAL – INDES. Au recto, cachet de passage PARIS (60) du 9 juin 1853, puis de transit de BOMBAY JUL 21 1853. SUP. R.

When translated into English:

N°1 + 5, Pair of 40c. bistre-yellow + pair of 10c. orange obliterator PC 2388 on letter struck with circular postmark of PAU dated June 7, 1853 to BENGAL – INDES. On the front, stamp of passage PARIS (60) of June 9, 1853, then of transit of BOMBAY JUL 21 1853. SUP. R.

N°1 + 5 refers to Yvert & Tellier catalogue no. 1 and 5 i.e. the very first stamp issues of France. PC means the losange (diamond) petit chiffres (small numbers) obliterator used to cancel the stamps; no. 2388 was allotted to Pau.

So, the French describer (I presume) does a pretty good job as far as the postal history of France goes but refrains from commenting much on the Indian aspects.

In this piece, I will cover some social and political history; and then talk about a kind of uniform half anna postage which was experimented with in the newly annexed territory of Punjab, a full five years before it was introduced all-India.

Anderson Correspondence

Letters from France to India dating to the early 1850s tend to be, in the majority, from the Anderson correspondence.

This letter was written from Pau in France by Warren Hastings Anderson (1796-1875). The recipient was his son, Captain (later General) David Murray Anderson (1821-1909) of H.M. 22nd (Cheshire) Regiment of Foot.

Born on 12 August 1821, Anderson was commissioned in the British Army in 1838. He would have arrived in India with the 22nd in May 1841. When this letter (concerning family matters) was written, Anderson was serving in the recently annexed Punjab region of India.

Later, Anderson was the last Governor of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst (Figure 2) from 1886-88; after him the post was merged with that of Commandant of the college. He was promoted to a full General during this period.

Anderson died in 1909 aged 88.

A digression into Charles Napier’s Peccavi

H.M.’s 22nd Regiment was in India from 1841 to 1855 and were the only English unit to participate in the Scinde campaign of 18431 under Charles Napier (Figure 3). I won’t be able to resist a brief digression into the man and say Peccavi in advance!

In 1842, Sir Charles James Napier (1782-1853) was a Major-General in the Bombay Army when he was asked to put down rebels in Scinde (or Sind in present-day Pakistan). However, he exceeded his brief by subjugating the entire province and having it annexed to Bombay Presidency in February 1843.

It is thought that on conquering the region, he sent a one-word despatch to his superior, the Governor-General of India Lord Ellenborough (1790-1871) – Peccavi – which means “I have sinned” (a pun on “I have Scinde”).

However, this story is apocryphal. The true author of the pun was an English teenage girl, Catherine Winkworth, who submitted it to Punch. The satirical magazine then printed it as a factual report in its issue of 18 May 1844 (Figure 4).

Moving towards Postal Reform in India

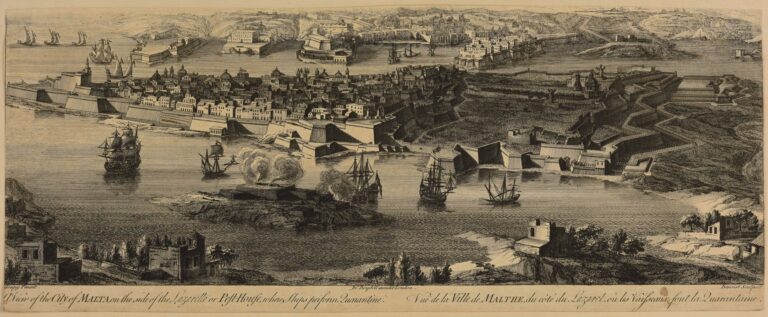

Figure 5 shows another letter from the same correspondence. It is was sent more than a year earlier than the one shown above and is datelined 22 March 1852. It would have reached Captain Anderson at Rawul Pindee sometime towards end-April of that year.

At the town of Pau in France, the letter was stamped with a pair of the 1849 Cérès one franc dark carmine (Yvert & Tellier no. 6; again a first issue). The two franc prepayment indicates that it was a double letter weighing between 7½ and 15 gm. This is the only double weight letter from France to India from this correspondence that I have seen till date.

(Update: I have since found three more double letters. One is shown in the 2010 Classic India & Scinde 1600-1858 published in the Edition D’ Or series showcasing Jochen Heddergott’s exhibits. Another two are illustrated in the 2009 Cérès 1849, les premiers timbres de France et ses usages postaux which is based on Joseph Hackmey’s collection.)

The rate of 1 franc per 7½ gm single existed from 1 August 1849 and 31 December 1856. Note that the rate paid the letter only to Alexandria in Egypt and not beyond (Figure 6).

On arrival at Bombay, the letter was struck with the handstamp ‘BOMBAY / AP20 1852 / STR. POSTAGE {8} / INLD DO {15}’ (Giles SR6).

The numbers 8 and 15 (in this as well as in the letter shown as Figure 1) imply that steamer (or steam) postage of 8 annas for the carriage from Alexandria to Bombay and inland postage of 15 annas for the distance between Bombay and Rawul Pindee (Rawalpindi in present day Pakistan) was due from the recipient.2

Why 15 annas?

The 15 annas inland postage from Bombay to Rawul Pindee is difficult to understand at first glance.

The latest inland rates were as established under the Indian Post Office (Act XVII of 1837) effective 1 October 1837. Further Act XVII of 1839 amended sections VI and IX of the 1837 act, which dealt with inland and ship postage rates respectively, allowing changes to be made to them by the Governor General of India.

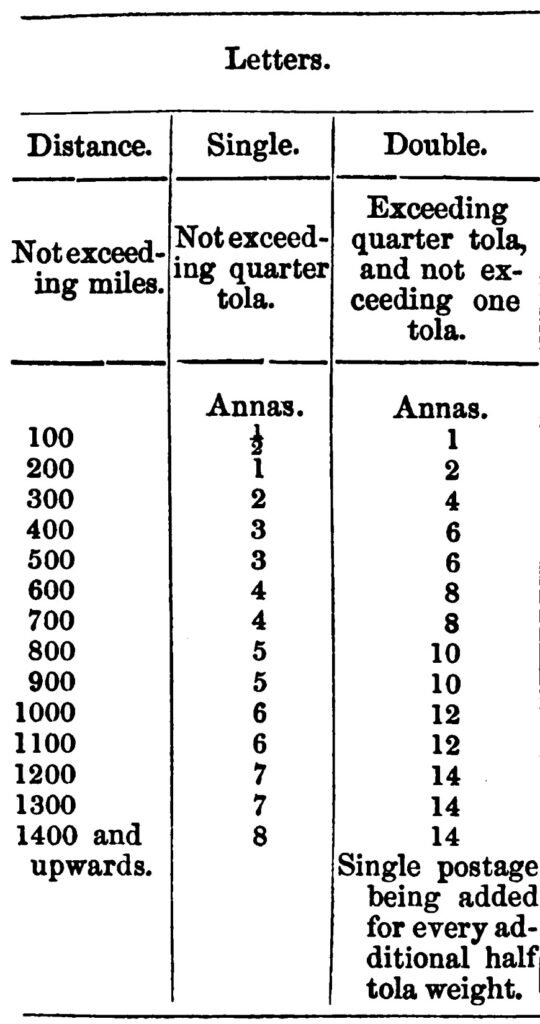

Shortly thereafter, on 14 August 1839, the Governor General exercised his authority reducing inland rates while also bringing in a new single rate scale of quarter tola (mainly to encourage letters written by Indians) to be effective 1 October 1839. Figure 7 shows the new rates for letters.3

The rates in the above table don’t show any odd numbers in the double weight column. How was 15 annas sought to be charged by the post office then?

Postal Experiment in Punjab

The Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1848-49 led to the fall of the Sikh empire and the acquisition of Punjab and what later became the North-West Frontier Province (not to be confused with North West Provinces of India) by the East India Company. The then Governor-General of India, James Andrew Broun Ramsay (1812-1860), better known as Lord Dalhousie (Figure 8) proclaimed the annexation on 29 March 1849.

Notwithstanding his politics and imperialistic attitudes, one needs to give credit where it’s due – Dalhoiusie’s interest in post office reforms in India.

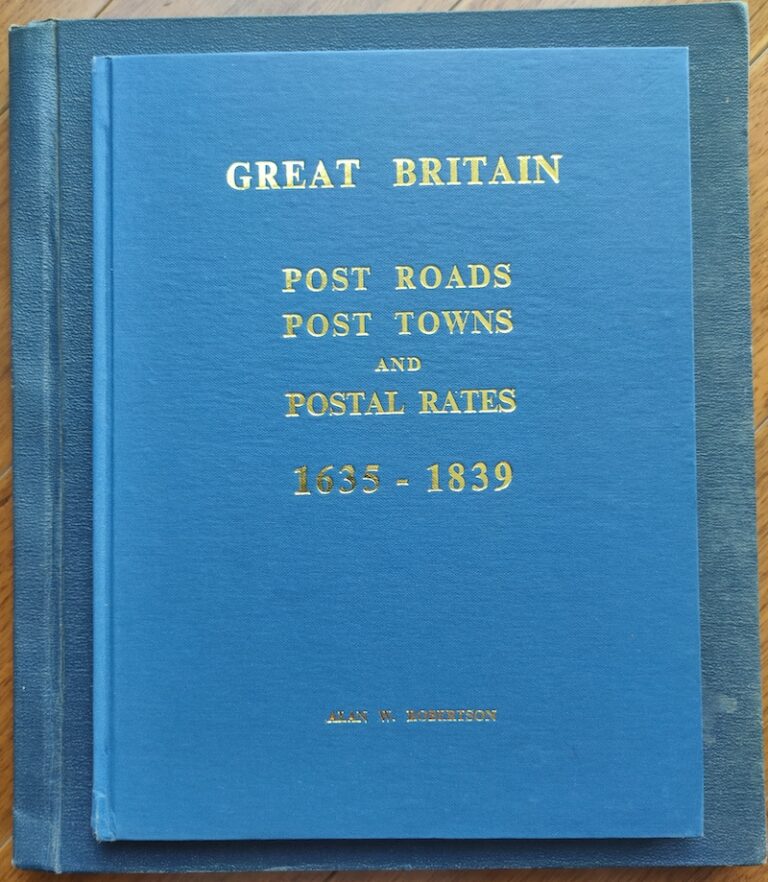

Dalhousie landed at Calcutta on 12 January 1848 as the youngest Governor General aged just 36.4 In England, he had been the President of the Board of Trade and also a member of the Cabinet in an earlier government. He was quite aware of the postal revolution in Great Britain brought about in 1840 by the introduction of stamps, uniform penny postage, and more, and wished to implement something similar in the new country. After years of struggles, including with the Court of Directors of the East India Company in London, he managed to get what he wanted. Uniform half anna postage5 was introduced in India effective 1 October 1854.6

But that’s some years in the future. Let’s dial back to 1849 when the Indian government reached its final frontier in the North-West when it annexed Punjab;7 remember Scinde, to the south, had been taken in 1843.

Postal services in Punjab for public use was virtually non-existent. And the existing postal system of India, with its high postage rates and inefficiencies, was extended to the newly conquered area. So it was a double whammy.

Dalhousie felt, “Nothing could be worse than the condition of the Post office on the frontier.” And that “…it is not likely to be improved in the new country beyound, unless the screw is put on.”

It was in the “new country beyound” – Punjab – that the first official experiment in India with a kind of reduced uniform postage rate took place.

In May 1849, in the town of Simla at the foothills of the Himalayas, Dalhousie is said to have met with James Thomason, Lieutenant Governor-General of North West Provinces (NWP)8 and H.B. Riddell,9 Post Master General of NWP.

Soon thereafter, Riddell proposed to the Government of India that rates of postage to places “in the new Territories” be reduced. Dalhousie concurred stating in a minute issued on 12 June 1849:

Having regard to the particular circumstances under which the correspondence is at present carried on with distant stations in the Punjab, I think it reasonable that a reduced rate of postage should be demanded by the Government.

In his letter dated 21 June 1849, the Secretary to the Government of India communicated approval for the “diminution of the rate of Postage” to Riddell.

Armed with this sanction, Riddell issued a notification from Agra, then capital of the North West Provinces, on 5 July 1849 (Figure 9) which reduced “…as a temporary measure…the postage chargeable on Letters from places beyond the limits of the Punjab to the Stations enumerated…”

One of the stations was Rawul Pindee (or Rawulpinde as the notification spelt).

What was the reduction?

…from the date of receipt of this Circular, the single Postage10 to be levied on Letters for any of the above-mentioned Stations, will be Half Anna in excess of that which would have been charged if the Letters were addressed to Lahore.

In other words, a letter going beyond Lahore (the capital of the erstwhile Sikh empire and Punjab’s premier city) would be charged a fixed rate irrespective of the distance it traveled.

Therefore, while limited in its scope, this was the first uniform postage system to be officially implemented in British India.

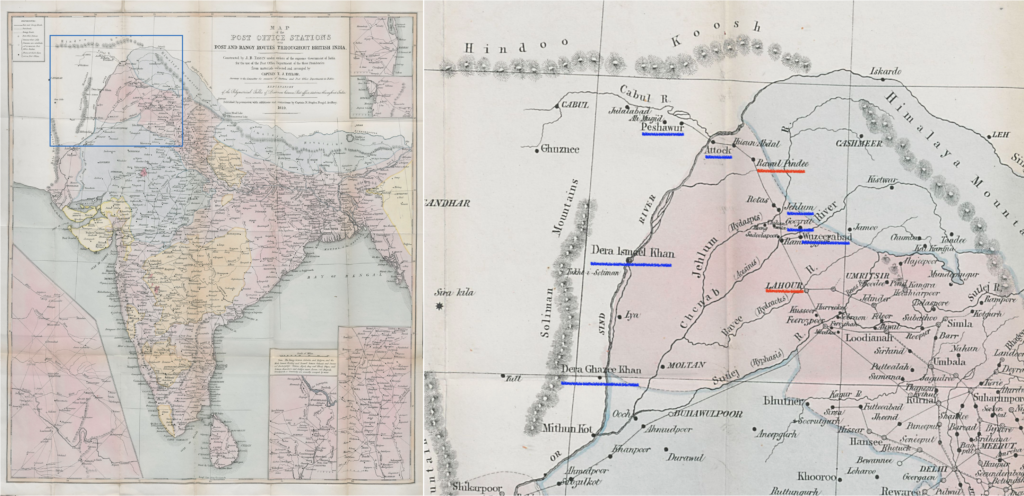

Figure 10 identifies some some of the stations in the new territories referred to in the aforesaid post office notification. The distance from Lahore to Wuzeerabad was about 70 miles while that to Peshawur some 280 miles. That didn’t mean increased postage on letters to Peshawur vis-à-vis Wuzeerabad.

Before moving on, some questions arise (with my short answers in brackets with some elaboration later):

- Was it a really an initial and important step in the road to postal reform? [No]

- Or was it that the postal system in the new province was so fledgling (using a polite word!) that the government didn’t have the moral authority to demand the (high) postage rates prevailing in the rest of the country?11 [Yes]

- Did Dalhousie and his close advisors on this matter have an inkling that this action of theirs would culminate five years later into uniform and reduced postage rates across India? [Don’t think so, but Dalhousie was clearly gunning for postal reform]

In April 1850, Dalhousie caused three Commissioners to be appointed who were to inquire into and report upon the existing postal system, its defects, and possible remedies. Further, they were directed to consider the possibility of introducing a uniform low rate of postage in the “whole of the British Territories in India.”

Now, when Riddell gave his opinion to the Commissioners, he didn’t even mention the Punjab initiative. And, it doesn’t find any mention in the massive Report of the Commissioners for Post Office Enquiry published in 1851.

This indicates that the 1849 step served as no great inspiration for what came ahead. While it may have been at the back of their minds, its instigators themselves didn’t take it seriously; at least seriously enough to talk about it publicly. Talk of postal reforms was anyway in the air and many, both within the government and outside, were talking and writing about it.12 Even if Punjab had not been annexed and consequently this measure not introduced, progress towards postal reforms would have been as sure and steady; as long as Dalhousie was driving it, of course.

But, as far as us postal historians are concerned, we can see it to be an important point in the postal history of India – the first instance in the country when uniform low postage rates were formally applied on letters.13

15 annas explained

Coming back to the entire letter and 15 annas. The distance between Bombay and Lahore was between 1100 and 1300 miles. Per the table of rates in Figure 7, postage on double letters (weighing ¼ to 1 tola or 2.92 to 11.66 gm) between these two places was 14 annas. For Ruwal Pindee, which lay beyond, one anna (double of half anna since it’s a double weight) had to be added. This totals to 15 annas.

Was the rate reduction “temporary”?

The answer is no. I haven’t found any evidence that the notification discussed earlier was ever withdrawn until the new Indian Post Office Act of 1854 superseded it.

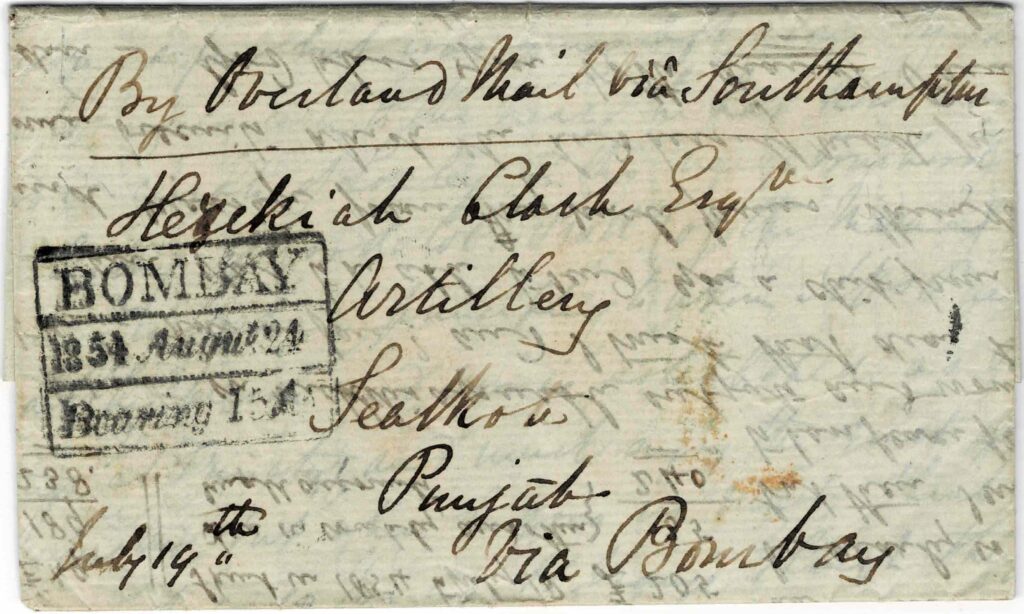

And evidence from postal history items such as the ones in Figure 1 (July 1853) and Figure 11 (August 1854) confirms.

Figure 11 shows an incoming letter from GB reaching Bombay on 24 August 1854 and then redirected to Sealkote (today’s Sialkot), which is about 25 miles to the east of Wuzeerabad. Inland postage of 15 annas, i.e. exactly the same as the letters in Figures 1 and 4, is shown as due.

The observant reader will note that Sealkote was not a station mentioned in the notification of July 1849. It was added later when a ‘Circular Memorandum’ dated 19 October 1850 was issued by Riddell. It said:

A Post Office subordinate to Wuzeerabad, has been opened at Seealkote, the Postage to be charged is that chargeable on Letters for Wuzeerabad, viz. for a distance of 60 miles beyond Lahore.

This notice makes one wonder if, as and when new post offices were opened in Punjab, the benefit of concessionary postage rates were extended to them.

Outgoing Letters from Punjab

The letters shown in figures 1, 5, and 11 are incoming letters (from abroad) which demonstrate the implementation of the half anna uniform postage in Punjab. Figure 12 shows an outgoing inland letter from Peshawur to Calcutta (western frontiers of India to extreme east) which paid 7½ annas rather than 8.

Theoretically speaking, the notice of July 1849 applied the concessionary rates only to letters “for any of the above-mentioned Stations” (incoming letters) and not to those from these stations to places in India (outgoing letters) or to inter-province ones (internal letters). So,it could be that the implementation of the said notice was different in practice. Or a subsequent notice, yet unknown, extended the concession to outgoing and possibly internal letters.

References

- Das, M.N. “Dalhousie and the Reform of the Postal System.” in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 21 (1958): 488-495

- Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. “The Utilitarianism of Dalhousie and the Material Improvement of India.” Modern Asian Studies 12, no. 1 (1978): 97-110

- Giles, D[erek]. Hammond. Catalogue of the Handstruck Postage Stamps of India. London: Christie’s Robson Lowe, 1989

- ———. The Hon. E.I.C’s Steamers of 1830 – 1854. Handbook of Indian Philately. London: The India Study Circle for Philately, 1995

- Report of the Commissioners for Post Office Inquiry, with Appendixes. Calcutta: Military Orphan Press, 1851

Notes

- After the Scinde campaign, the 22nd Regiment were mainly stationed at Bombay and Poona. They never took part in the second Anglo-Sikh war of 1848-49 which is discussed later. They were ordered to the North-West Frontier where they were in the early 1850s. By 1855, they were back in England. ↩︎

- At this time, 16 annas = 1 Rupee = 2 shillings = 24 pence = 2.40 francs ↩︎

- Apart from letters, new schedules of rates were published for (a) Law papers, accounts and vouchers, (b) Public Banghy (i.e. parcels), and (c) Books, Pamphlets, Packets of Newspapers, and any written or engraved papers sent by Public Banghy. ↩︎

- While he was young, Dalhousie was also physically weak. When he landed at Calcutta he was, in his own words, “an invalid, almost a cripple”. He took ill frequently and died at the age of 48, four years after leaving India. ↩︎

- Dalhousie was also responsible for the introduction of the railways and electric telegraph in India. He called them, along with uniform postage, as the “three great engines of social improvement.” ↩︎

- The reader would have noted three dates of 1 October from which new postage rates were effective – that from 1837, 1839, and 1854. ↩︎

- Beyond lay Afghanistan where the British had suffered a humiliating defeat in the first Anglo-Afghan war of 1838-42. There were future wars but Afghanistan was never truly conquered and occupied by any imperial power. ↩︎

- Sometime in 1848, James Thomason had advocated to Dalhousie an experimental trial with a system of uniform postage at Lucknow. Dalhouse was directing the Sikh war and wrote back on 11 December 1848 from a camp near Umballa, “Personally I am favourable to a system of uniform postage rate,” and agreed on the advantage of Lucknow being the scene of first trial. ↩︎

- Riddell’s full name was Herry Philip Archibald Buchanan Riddell. It was usually shortened to H.B. Riddell in government records. Riddell was associated with the Indian post office from March 1844 till March 1867. When the new Post Office Act of 1854 was passed, Riddell was appointed as the first Director-General of the Indian Post Office. ↩︎

- As can be seen from Figure 7, single letters were those that weighed up to ¼ tola, double those between ¼ and 1 tola, treble between 1 and 1½ tolas, and so on. 1 tola is approximately 2/5th of an ounce of 11.66 gm. ↩︎

- Note the words used by Dalhousie: “…circumstances under which the correspondence is at present carried on with distant stations in the Punjab…” ↩︎

- One example is the Observations… book referred to in Figure 10. Further, the Report of the Commissioners for Post Office Inquiry published in May 1851 details the 10 proposals for post office reform that had been submitted to the Government; most of these were from various government officials. ↩︎

- A couple of years later, between October 1851 and June 1852, the commissioner of Scinde district, Henry Bartle Frere, undertook postal reforms when he brought in uniform half anna postage (per half tola weight) and introduced the famous Scinde Dawk stamps, the first in Asia. Both the rate and the stamps were applicable only in Scinde though. But this is a topic for another day. ↩︎