This article was published,with some modifications, as “India’s First Ship Despatch Handstamp″ in India Post 57 no. 1 whole no. 226 (January – March 2023). India Post is the journal of the India Study Circle for Philately. I have made changes to this blog post in January 2023 so that it is up-to-date.

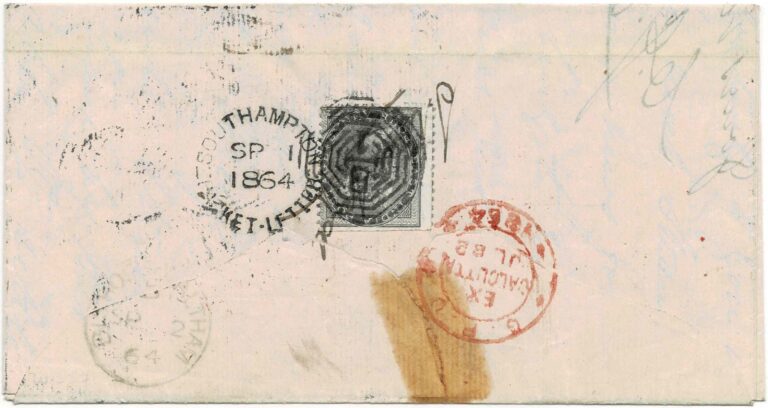

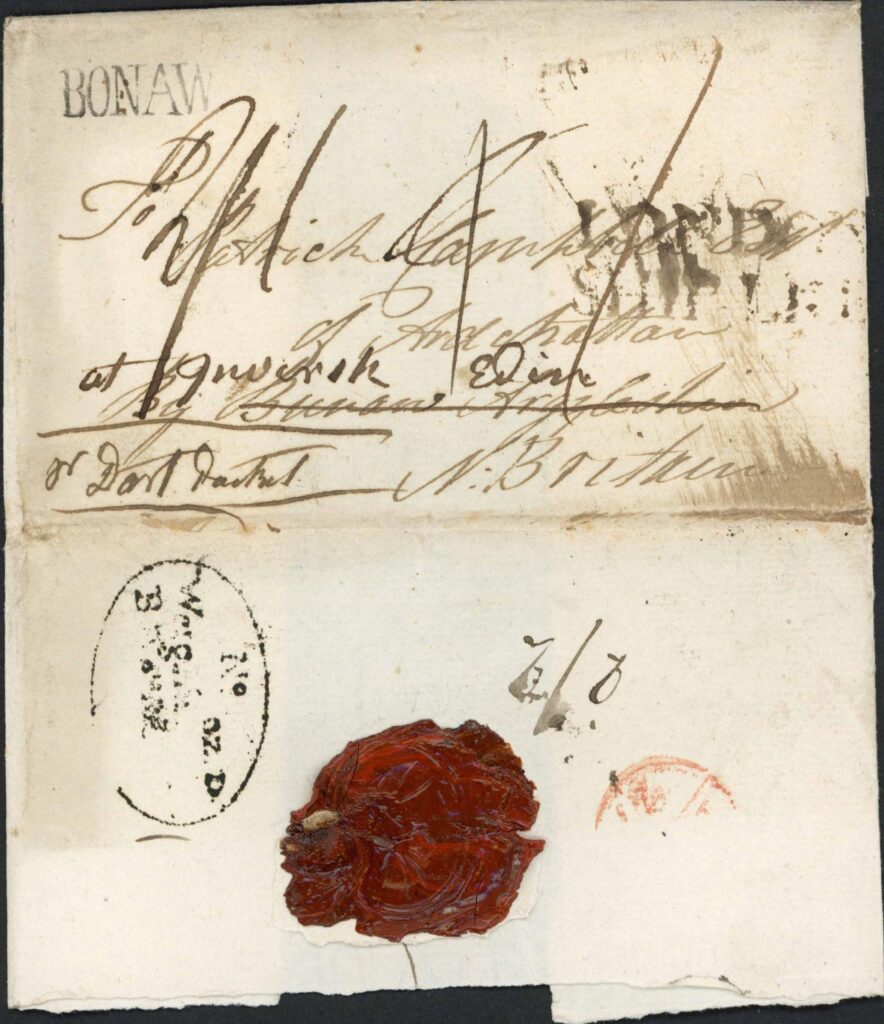

The appearance of a 1795 Calcutta to Scotland entire in a recent Cavendish auction (Figure 1) bearing a rare Calcutta handstruck stamp inspired me to write this piece.

The handstruck stamp I am talking about is a ‘Ship Despatch’ stamp type Giles SD1. Giles refers to Derek Hammond Giles, one of the greatest postal historians of India (Figure 2).

Before we get into the postal history aspects, a brief background. The East India Company (EIC) was incorporated on 31 December 1600 and had a monopoly on trade with East Indies and later East Asia. Initially the company was a humble trader; but starting with the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the warring Company slowly eroded the authority of the local rulers and effectively assumed the powers of a sovereign state. Many influential British personalities including members of Parliament were its shareholders and hence turned a blind eye to its (mis) deeds.

Nevertheless, constant warfare had led the company into deep debt. So as to protect their interests, the British Government proposed and Parliament passed the Regulating Act of 1773 and shortly thereafter the East India Company Act of 1784 (also called Pitt’s India Act after the William Pitt the Younger, who just 24 when he became the Prime Minister of Britain in 1793). The latter provided for the appointment of a Board of Control which was responsible for overseeing the EIC; its President was effectively the minister for the affairs of the EIC.

Genesis of Ship Letter Charges

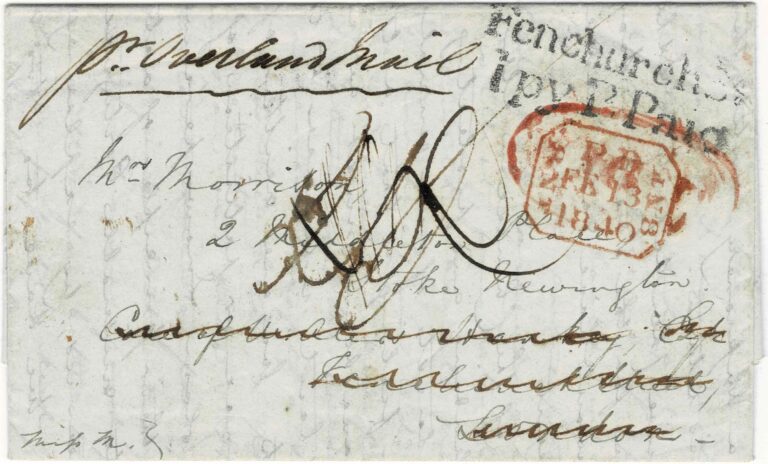

As of 1793, the EIC ruled parts of India including the cities of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay. Letters written by the expatriate community comprising of mostly Britishers, but also Europeans of other nationalities, were carried to Great Britain and Europe by the ships of the EIC free of cost.

It may have come to the notice of the Court of Directors of the EIC that this facility was being misused and some were sending heavy private letters and packages. Hence, in a letter dated 5 June 1793 addressed to the Governor General in Council (Charles Cornwallis when it was written but John Shore by the time it arrived in India), the Court of Directors of the EIC gave the following directions:

Every Private letter or Package, which weighs more than Two Ounces, to be taxed with the Payment of four Sicca Rupees; every one exceeding Three Ounces, nine Sicca Rupees; and others of a yet greater Weight, to be charged, in like manner, with the Rates formed of the Squares of the Number of Ounces which they exceed in weight – for example, any letter or Package which exceeds Two Ounces, to pay Four Rupees; any that exceeds Three Ounces Nine Rupees; any that exceeds Four Ounces Sixteen Rupees; and so on :- And no letter which is rateable with Postage to be received into the Packet, without the Postage being paid, and the Weight written on the cover.

(1 Sicca Rupee approximated 2 shillings 4 pence at this time)

Note that there was no ship postage payable on letters weighing below two ounces. The intention behind the order is clear – to discourage private individuals from burdening the ships with heavy packages while still allowing communication with their family and friends.

The directions so received were published in the Calcutta Gazette of 5 December 1793 (order dated 4 December), the (Madras) Courier of 20 December 1793 (order dated 7 December), and in the Bombay Courier of 28 December 1793.

The rule would have been implemented in the three Presidencies of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay immediately. The scrupulous William Jones, Postmaster General of the General Post Office at Fort St. George, Madras for instance, issued a notice on 21 January 1794 that certain letters weighing above two ounces that were lying in the post office would not be forwarded until the tax as stipulated was paid; it then went on to list the names of the recipients (Figure 3).

The Handstamp

This introduction of ship postage to the creation of India’s first handstruck ship despatch handstamp at Calcutta – the famous Giles SD1 (Figure 4). It is also the one handstamp from the pre-stamp (pre-1854) era mentioning ounces; ounce, as a weight measure, was not used locally in India.

While Giles mentions only three examples have been recorded, there are more, and the total number may be pushing into double digits. Ironically, a handstamp created on account of the ‘more than two ounces’ rule, has only been seen applied on letters weighing less than that weight!

Now, the order of the Governor General in Council and issued by the Public Department on 4 December 1793 (signed by E. Hay, Secretary to the Government) mentions:

The Honourable Court of Directors having directed that a Person belonging to the Secretary’s Office, being a Covenanted Servant, shall be appointed to carry these Regulations into execution Mr. Richard Ahmuty, the Head Assistant in the Public Department, has been ordered to undertake this duty.

Mr. Ahmuty, by whom alone Letters or Packages, to be transmitted in future to Europe in the Government Packets, are to be received, will attend to his Office, in one of the lower apartments at the Council House, for ten days previous to the day fixed for the dispatch of a Packet, Sundays excepted, between the hours of ten in the morning and four in the afternoon, and again between the hours of seven and nine in the evening, for the purposes pointed out in the Company’s Orders.

It will be necessary that Gentleman at a distance from Calcutta, should instruct their Agents or Friends at the Presidency to cause their Letters to be delivered to Mr. Richard Ahmuty, instead of sending them, as has frequently happened, under cover to the Secretary, or the Gentlemen in his Office, for transmission by the Packets.

For reasons we can well speculate on, the authorities decided that a person from a government department different from the postal one would be responsible for receiving letters and collecting the tax due. So, did Mr. Ahmuty pass all letters received by him to the staff at the post office (quite likely) or did he deliver them on board the ships himself? Was the idea of this handstamp his or his superiors; or was it of the post office, as with other handstamps?

It is not known if persons corresponding to Mr. Ahmuty in Calcutta was appointed at Madras and Bombay. And, no corresponding handstamps as in Calcutta was ever issued in Madras or Bombay; at least we haven’t yet seen one.

Analysis of the Handstamp

Now let’s analyse the handstamp closely. The word ‘No.’ on the first line indicates that the intention was to number individual letters for record keeping purposes. However, none of the existing copies have any manuscript number filled in against it.

Second, ‘Oz. D’ denotes ounces and pennyweights; 20 pennyweights being equal to a troy ounce and 18.23 to an avoirdupois ounce.

As per the Research Group led by Col. C. N. M. Blair which resulted in the India Study Circle’s publication, India-U.K. Mails, there are two interpretations for ‘B.P. Sa.Rs.’ One being ‘Bearing Postage Sicca Rupees’ and the other being ‘Bengal Postage Sicca Rupees’. If, as we have seen from the aforementioned order, ship letter charges were supposed to be collected in advance, the former would not make sense.

Most examples of the stamp don’t have any manuscript markings inside. However, some do have numbers; one in the Michael Manning Sale of 2015 had a ‘3’ (Figure 5), one in the collection of someone I know has a ‘5’, and yet another has a ‘1/1’.

Now, one can conjure up some thoughts on what these numbers imply. Do they denote the postage paid? No, since these numbers i.e., 3, 5, and 1/1, do not correspond with the rates of Rupees four, nine, 16, etc. stipulated. Do they reflect some kind of numbering by Mr. Ahmuty? No, since the place to put in any filing number was right at the top.

The only theory that one can give credence to is that they denote the weight of the letter. So ‘3’ and ‘5’ would mean three and five pennyweights respectively (about 4.67 and 7.78 gm) and ‘1/1’ would mean one ounce one pennyweight (29.90 gm). This would also imply that the row containing ‘B.P. Sa.Rs’ was left blank in each of the three cases; understandable since these letters didn’t exceed two ounces and hence no postage was payable on them.

Demise of the Ship Letter Charges

This handstamp has been found used only in 1794 and 1795. There is a good reason for it. The June 1793 order may have triggered resentment and objection amongst the local expatriates. Hence, by a letter dated 6 May 1795, the Court of Directors decided to abolish this rule.

Having reconsidered our Orders of the 5th of June 1793, directing that all private Letters for Europe, weighing more than Two Ounces should be subject to a certain Postage, we have thought proper on account of the inconvenience which we understand Individuals have sustained thereby to revoke the same.

The letter was published in the Calcutta Gazette of 8 October 1795 (order dated 29 September) and Madras Courier of 9 September 1795 (order dated 5 September); it would surely have been published in the Bombay papers as well; however, I haven’t been able to trace that yet.

References

- Giles, D. Hammond. “The Ship Letter Despatch Stamps of Calcutta.” India Post 4 no. 5 whole no. 23 (Sep/Oct 1970): 113-116.

- Giles, D. Hammond. Catalogue of the Handstruck Postage Stamps of India. London: Christie’s Robson Lowe, 1989

- Blair, Col. C.N.M., and D[erek]. Hammond Giles. India – U.K. Mails. The India Study Circle for Philately, 1973-1981