Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (Figure 1) is remembered as the most important personality in the development of the ‘Overland Route’ between Great Britain and India in the 1830s.

For almost 200 years, he has been hyped up as a paragon of virtue: someone with boundless energy and enterprise who toiled endlessly to realise his dream of hastening communications between the East and West, but was ultimately hard done by lack of wealth and resources, bureaucratic officials, and well-endowed competitors.

In reality, he was a complicated man.

Recent researches has shown that was not so perfect with many shortcomings – volatile and quick to temper, a disdain for authority, sprouting falsehoods, and even being less-than-honest with the British government and his own correspondents.

Plenty has been written about the positives of the man and hence, we will not get into them. Recognising the frailties of all human beings and without being judgemental, we take a look at some of his lesser known facets.

Other Sides of Waghorn

Munich-based Jochen Heddergott has been collecting Indian postal history for 50-odd years. Suffice to say, he is one of its pioneers. Of particular interest to him is the development of the overland route. Unfortunately for Waghorn aficionados, especially amongst us postal history collectors, Heddergott does not think much of him.

In the handout to a presentation1 that was made in 2014 (Figure 2), he notes:

His reputation nowadays is much better than in his time. The references found in India House, London, painting a much different picture than expected, depending on Sidebottom and Mrs. Sankey,2 who believed too much in the publications of the London Times, whose correspondent and agent Waghorn was and got paid by her.

Illegal Fees

Heddergott narrates an interesting incident which throws light on Waghorn’s Janus-like character.

In June 1837, Waghorn was appointed ‘Deputy Agent to the East India Company in Egypt’ at a salary of £300 a year. He was placed under Lieutenant-Colonel (later General) Patrick Campbell, the British Consul-General in Egypt. Nevertheless, he was permitted to continue his private forwarding business.

Shortly thereafter, Waghorn started abusing his official position by charging his fees on all letters which came to his hands. The Consul General of Holland in Alexandria, Mr. Schultz, complained to Campbell, who was extremely annoyed. In a letter of 30 October 1837, he wrote to Waghorn:

I can perfectly understand the nature of the payments made to your agents in England and India…the case of Mr. Schultz, Mr. Alex Thurber, Mr. Agnew and others is perfectly distinct.

Waghorn had to return all the illegally charged money. In the coming months, his relationship with Campbell became increasingly strained over other issues. The Company sided with the latter and by December 1837 Waghorn had been stripped of his post; he had held it for just six months.3

Since Waghorn was in the good books of the Pasha, Mehemet (or Mahomet) Ali, he could not be totally ignored. So, when Campbell went to visit the Pasha in May of the following year, Waghorn was present in the delegation (Figure 3). In October 1839, as we shall see later, the Pasha permitted Waghorn to use his steamer to take Indian mails further westward; Campbell not only allowed this (or was compelled to by the merchants), but also issued Waghorn a general passport.

False Promises

Even since he started his forwarding business, Waghorn claimed that letters and parcels entrusted to him would be invariably delivered many days earlier than those going through the post office.

Heddergott quotes Campbell, who was being prescient as well as calling out Waghorn’s bluff, when he wrote in a letter dated 22 February 1837:

…I think Mr. Waghorn totally unfit for this undertaking…he is very intemperate and possesses so little judgement…I do not see anything which he has done here…as it is a fact that the boxes sent through the Consulate monthly have reached their destination precisely at the same time as those sent through the channels of Mr. Waghorn, the only difference being that those sent to Mr. Waghorn pay a heavy postage while the other do not pay any…

Heddergott has researched the time taken by letters, ones forwarded by Waghorn and those sent in the normal course through the post office, in reaching their destination. He did not find any advantage offered by the former.

None of the 164 covers recorded (going East to West) arrived one or more days earlier than any other cover from India to Europe transported on the same route.

Further, he faults Waghorn for being disingenuous:

When Waghorn wrote, that his covers were faster than the covers sent by the officially (sic) route, he forgot to mention, that he compared the time taken via Marseilles against the time taken via Falmouth. Any Waghorn covers via Marseilles arrived in London at the same time as any packet sent by the official mail via Marseilles, and any covers via Falmouth reached London absolutely at the same time as Waghorn covers via Falmouth.

Therefore, Heddergott quips:

He was the only Agent who took money for something the others did for free.

Another expert, Frederick Rowland Hill wrote a number of articles on Waghorn in the Egyptian Study Circle’s Quarterly Circular in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He extensively used the Letter Book of Waghorn’s Alexandria Office for the period January 1840 to February 1841.

Hill confirms that Waghorn was prone to make promises which he never fulfilled. One such was made in his ‘flyer’ of June 1840. It is with respect to periodicals.

PERIODICALS to Bombay average thirty-seven days from the time of their despatch from London.

However, the actual experiences of the previous six months beginning January 1840 painted a different picture. In that period there was only one month in which there was any chance of periodicals arriving in 37 days; whether they did so is unknown. Hill concludes:

Waghorn seemed to claim, as usual, not what was done, but what ought to be possible; and things did not improve.

Both Heddergott and Hill bring Waghorn down several notches from the high pedestal he occupies in our minds. We can now see all sides of the man – the good, the bad, and the ugly!

Sailing on the Generoso

There was one instance though when Waghorn sailed, figuratively and literally, to the rescue thereby justifying his reputation of being indefatigable. This occurred in October 1839 when he transported about 35,000 letters coming from the East Indies contained in 36 large packages by convincing the Egyptian authorities to lend him the Pasha’s steamer, Generoso (The Evening Chronicle of 8 November 1839), which he captained and navigated. Magnanimously, he did not just take the letters that were meant to be forwarded by him, but all letters.

Letters affixed with the attractive handstamps of Waghorn’s agents in India, which were carried on this trip, do exist; they have appeared in past auctions.

What I present below are two letters sent in the ordinary way through the post office – one that was carried on the Egyptian steamer and one that should have been, but was not.

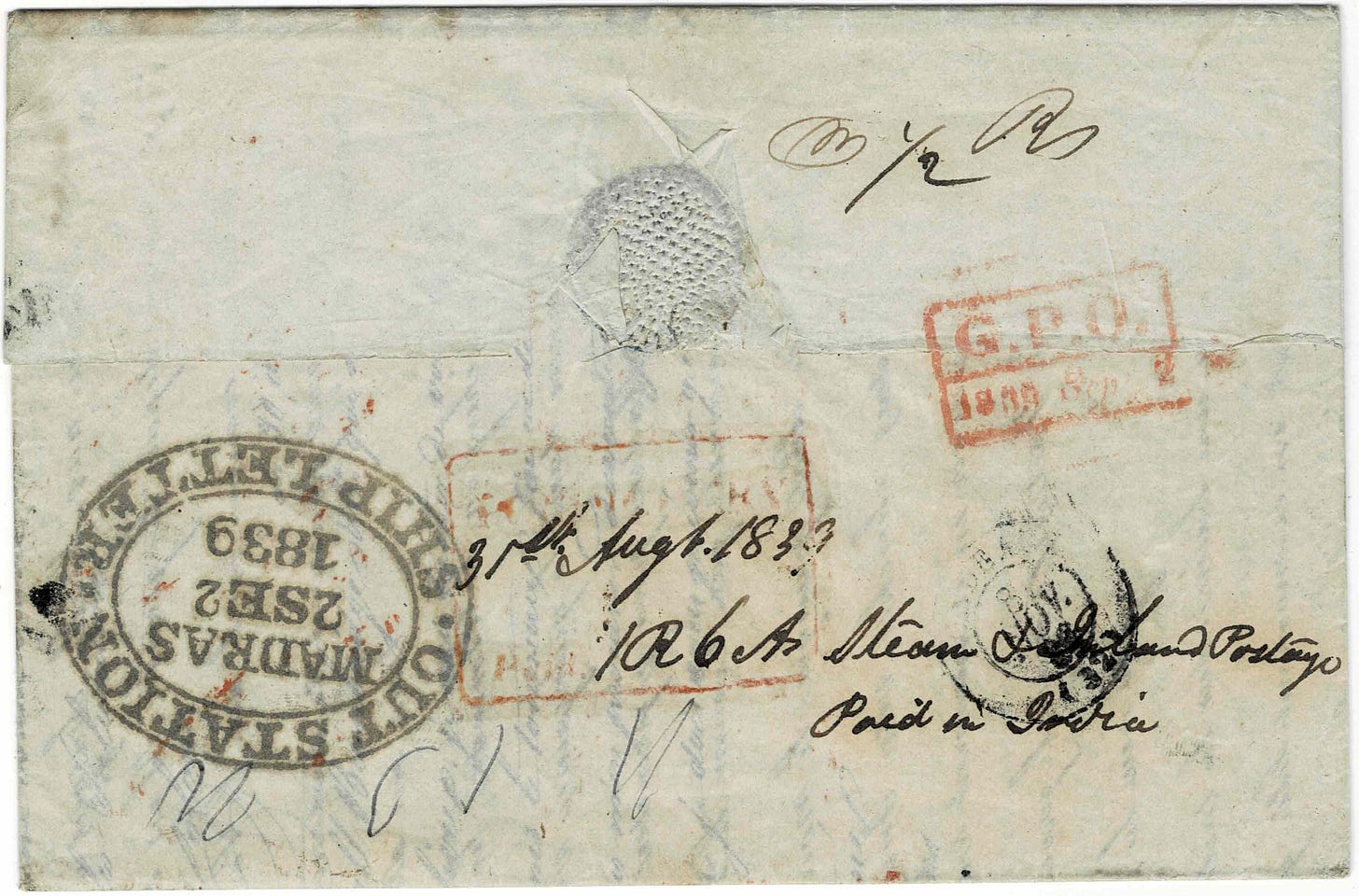

Figure 4 illustrates an entire letter that sailed on the Generoso. It is from the French possession of Pondicherry in South India and is datelined 22 June 1839. Written by Amaleic & Co., it was sent privately to their Bombay-based forwarding agent, Skinner & Co.

The agent received the letter on 14 July and posted it three days later (see rear top flap which reads: ‘Received in Bombay 14th July & forwarded on 17th do. / by Skinner & Co.’).4 It paid 9 annas steam packet postage for the carriage from India to Alexandria (see red ‘9 As’ on front top).5

The East India Company’s Brig of War6 Euphrates left Bombay on 20 July with the mails; but was found leaky and returned the same day. After repairs, she tried to go out again on the 22th but the tide was too strong for her to leave the harbour, and she returned to middle ground to anchor. She finally managed to sail on 23 July (Bombay Gazette of 22 and 24 July 1839).

Unfortunately, on her way to Aden, Euphrates became leaky again and had to be put into Isle of France (Mauritius) for six days for repairs. When she finally got to Aden is not known, but her mails were taken by the steamer Berenice to Suez (Bombay Gazette Extraordinary of 22 September 1839); the Berenice had left Bombay with mails of her own a month-and-half later on 13 September.

By the time all these letters reached Alexandria on 9 October, the admiralty packet, HMS Volcano, had already left.

What transpired next? The pro-Waghorn newspaper, Times, carried a detailed report on how Waghorn saved the day.7 It lauded him for his initiative while being less-than-kind towards Campbell. Excerpts from the report are given below:

On the 9th of October, two days after the sailing of her Majesty’s steamer Volcano from Alexandria, the India mails reached that port, having arrived at Suez on the 5th – viz., the July mail, by the Waterwitch, from Bengal; and the August mail, by the Euphrates,8 and the September mail, by the Berenice, from Bombay.

Upon finding, it is said, that Colonel Campbell had, on political grounds,9 declined accepting an offer of Mehemet Ali, through Mr. Briggs10 and Mr. Waghorn, to send one of his steamers on to Malta, with the mails…

The result was, that Colonel Campbell furnished Mr. Waghorn with a general passport, and he, with his accustomed intrepidity, embarked with the mails in the Pacha’s steamer Generoso, and landed them on the 18th inst.11 at Malta, whence they were forwarded on the following morning to Marseilles, and arrived here yesterday. Thus are the government and the East India Company indebted to the zeal and activity of Mr. Waghorn…

The Times also ran Campbell’s side of the the story supplied by his well wishers:

The imputation against Colonel Campbell, mentioned in the letters from Alexandria received yesterday, that he had declined the offer of the Pacha of Egypt of a steamer to convey the Indian dispatches to Malta, is wholly denied by his friends and connections in the City, who affirm that the arrangement for conveying the dispatches from Alexandria to Malta in the Pacha’s steamer was made by Colonel Campbell, and that he also engaged the services of Mr. Waghorn to take care of the dispatches during the passage.

Soon thereafter, Waghorn joined the slug-fest. The Times carried his letter dated 24 November written from Alexandria.12 Snippets from it follows:

When the mails got to Alexandria, Colonel Campbell took no steps for twenty-hours to get them sent on to Malta…

I next pressed the Colonel warmly to ask for the Pacha steamer Genoroso, and that I would go as messenger and navigator of her to Malta and back, which, after another twelve hours’ delay, he at last consented to do…

…but when the Pacha’s permission arrived from Cairo, which took two days more, the Colonel then declined taking. On the Colonel’s refusing to accept the steamer he had before asked for, Mr. Briggs and myself took up the matter with double zeal and interest; for we both felt that a great victory in India had been achieved by British valour,13 and that the sooner it was known in Europe, &c., the better; besides there were three months’ mails from the East in Egypt, and the sooner they could be got to England the better….

Briggs and myself then went to the Pacha’s Minister privately; we dwelt on the urgency of these mails, and how noble-minded it would appear in England among the merchants that Mehemet Ali’s Government gladly put a steamer at their use for their India letters after the official of their Government in Egypt had refused the acceptance of such favour on political grounds.

This argument had its full force with his Excellency Boghos Bey, the Minister in question. I next morning started with the mails for Malta….

When Colonel Campbell found out that the steamer was permitted by the Minister to start with the private letters from lndia ‘to my care,’ as well as the letters from the Alexandrian merchants, the Colonel then appointed Lieutenant Daniel, of the Indian Navy, to take the Government despatches as messenger, and not me. This appointment to Lieutenant Daniel was refused by him on the plea, that, as Mr. Waghorn had jointly with Mr. Briggs had all the trouble of getting the steamer, it was unjust to deny him the credit of taking the Government despatches, as well as his own. Colonel Campbell, on hearing this from Lieutenant Daniel personally, was obliged to order a new passport as messenger to be made in my name, and the one before signed for Lieutenant Daniel to be destroyed.

Given Waghorn’s tendency of self-aggrandising, one needs to take his letter with just a pinch of salt.

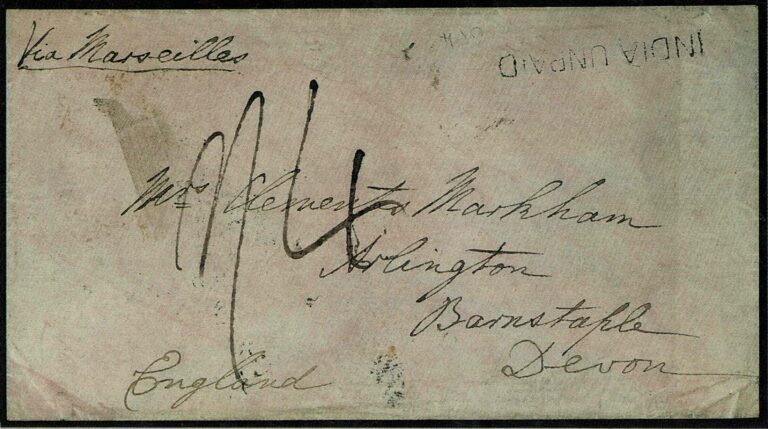

Figure 5 shows an entire letter which should have carried on the Generoso, but was not. Datelined 22 and 30 August 1839, it was posted at the British post office in Pondicherry on the 31st. Weighing under ½ tola or 0.2 oz (see ‘wg ½ Rs’ rear top), it paid total postage of 1 rupee 6 annas i.e. 13 annas inland postage to Bombay and 9 annas steam postage.

At Bombay, it was put on board the steamer Berenice, which left Bombay on 13 September. We have noted before that her mails, along with those of the Euphrates and Waterwitch, reached Alexandria on 9 October.

The Bordeaux date in this is 8 November, unlike the previous example where it is 28 October. This implies that the letter was not carried by Waghorn on the Generoso. Given their huge numbers, it is probable that some letters from the three dispatches arriving from India at the same time could not be accommodated on the Egyptian steamer.

How did this reach France then? The next admiralty steamer, HMS Megaera, reached Marseilles only on 10 November. So, despite the absence of a postmark of the French Post Office at Alexandria, the only possibility is that the letter took a succession of three French steamers – from Alexandria to Syra (Syros, an island in Greece), Syra to Malta, and Malta to Marseilles. A strange thing is that, while the Tancrède reportedly reached Marseilles on 1 November, the letter took seven days more to arrive at Bordeaux.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

References

Ashbee, Andrew. 2016. Zeal Unabated: The Life of Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800-1850). Snodland, Kent: The Author.

Giles, D. Hammond. 1995. The Hon. E.I.C’s Steamers of 1830 – 1854. Handbook of Indian Philately. London: The India Study Circle for Philately.

Sankey, Marjorie. 1964. ‘Care of Mr. Waghorn’: A Biography. Special Series 19. The Postal History Society.

Sidebottom, John K., and (Charles R. Clear). 1948. The Overland Mail: A Postal Historical Study of the Mail Route to India. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd for The Postal History Society.

Tabeart, Colin. 2002. Admiralty Mediterranean Steam Packets 1830 to 1857. Limassol, Cyprus: James Bendon Ltd.

Tristant, Henri. 1987. Les Lignes Regulières De Paquebots-Poste: Du Levant Et D’Égypte 1837 – 1851. (=The Regular Lines Of Packet-Posts: From the Levant and Egypt 1837 – 1851.). Paris: The Author.

- Heddergott’s presentation can be seen online (https://youtu.be/kWy3KatQwJM) but the audio and video is poor. ↩︎

- Details of the works of Sidebottom and Sankey are given in the References. ↩︎

- The curious reader who wants to read more of Waghorn’s time as Deputy Agent and his clashes with Campbell are referred to Chapter 5 of Ashbee’s book. ↩︎

- Based on other covers seen, Skinner & Co. would typically post the letters on the day the packets closed at the Bombay GPO. In this case, the packets must have been first advertised to close on 17 July 1839. But due to delays in getting the Euphrates ready for sea, the Post Office kept the bags open until noon of 19 July (Bombay Courier of 20 July republished in Bombay Gazette of 22 July 1839). ↩︎

- The single steam postage rate covered carriage of letters up to ¾ oz and was only in effect for six months from 10 July 1839 to 26 February 1840. ↩︎

- During the monsoon season, which ran from June to August, the under-powered steamers of the Company often found it difficult to battle the hard-blowing south-west winds. In 1839 and 1840, the Bombay government used two options in this period. One, they sent steamers to the Persian Gulf rather than the Red Sea. Two, they dispatched sailing vessels to Aden, where a steamer would take letters onward to Suez. ↩︎

- The entire report in the Times is produced in Appendix 1. This was republished in the London Evening Standard of 1 November as well as other newspapers. ↩︎

- This is erroneous and should say ‘July’ instead of ‘August’. ↩︎

- In the power struggle between the Pasha and the Ottoman Empire, Britain supported the latter. Further, just a few months earlier, the Second Egyptian-Ottoman War of 1839-41 has begun. At this time, there was a great deal of tension between Britain and Egypt.

So, to be fair, as ‘Her Majesty’s Agent and Consul-General’, Campbell had to necessarily keep politics in mind. Even though he was sympathetic to the Egyptian cause, he could not openly show his cards, as Waghorn could. Meanwhile, the British government dismissed him on 1 October 1839 for his views and replaced him with someone more billigerant. Campbell would have received this news sometime towards the end of that month or beginning of the next i.e. a few days after the Generoso incident. ↩︎ - Samuel Briggs (1776-1868) arrived in Egypt in 1801 and set up Briggs & Company two years later. He was the Levant Company’s consul in Alexandria until 1810 and also Britain’s consul-general in the late 1820s. Mehemet Ali gave Briggs’s firm the right of sale of Egyptian cotton in Britain. For over 60 years, the Briggs firm remained the best-connected and most influential of all merchants in Egypt. ↩︎

- Depending on the newspaper one refers to, Waghorn reached Malta on either 18th, 19th, or 20th October. I am going with the 19th as reported in a letter in the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle from Malta dated 20 October (Tabeart 2002, p.191). ↩︎

- The Times report, also containing Waghorn’s letter in full, is produced in Appendix 2. This was republished in the Sun (London) of 13 December 1839. ↩︎

- The ‘victory in India’ that Waghorn is referring to is the Battle of Ghazni that took place on 23 July 1839 during the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839-42. ↩︎