Philatelists collect and sometimes research/write on and/or exhibit postage stamps. Postal historians do the same with entire letters and envelopes.

As far as being interested in what the other does, it seems that a chasm exists. Quite many philatelists, who possess items of postal history, do not care to investigate postal rates, routes, regulations, or modes of carriage. Similarly, postal historians are loath to even identify the catalogue number of stamps on their covers; they are fine as long as they can read their values!

This article seeks to explore how fun things can get if the twain should meet.

Rate from India to GB

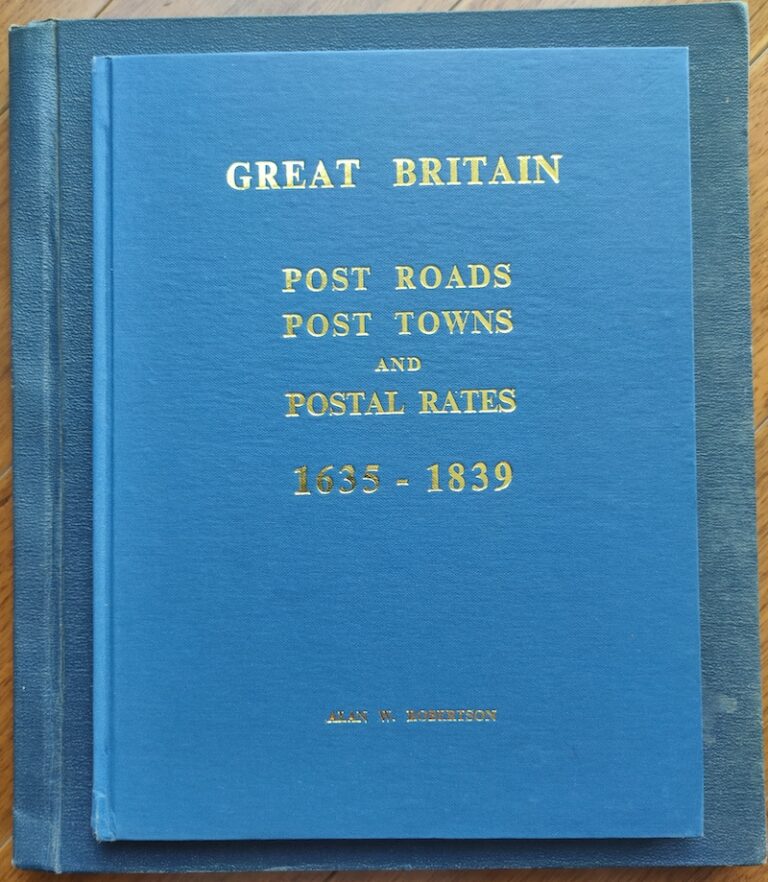

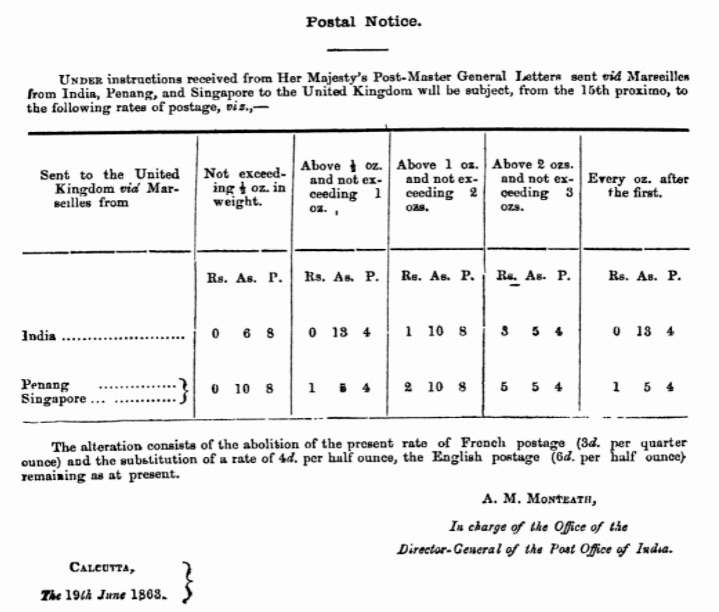

Effective 15 July 1863, the postage rate on letters from India to Great Britain (GB)1 weighing ½ oz and sent via the Marseilles route was changed to 6 annas 8 pies (6a8p) (Figure 1).2 This rate lasted for almost five years until 31 March 1868.

The number was made up of 4 annas (=6 pence) British postage plus 2 annas 8 pies (=4 pence) French transit charge. Further, of the 6 pence, 1 penny was to the account of the Indian Post Office3 and 5 pence was credited to the British Post Office.4

Stamps available then were of denominations of ½ anna, 8 pies, 1 anna, 2 annas, 4 annas, and 8 annas. Strangely, a 6 annas 8 pies or even 6 annas stamp was not issued for almost three years.5

Hence, the new postage rate had to be made up using stamps of lower values. For instance:

One stamp of 4 annas, one of 2 annas, and one of 8 pies. This franking is most frequently observed. Sometimes, in the absence of an 8 pies stamp, senders would overpay by using an 1 anna stamp.

The second most common combination seen on covers are three stamps of 2 annas and one of 8 pies.

It was also possible to use two stamps of 2 annas, two of 1 annas, and one of 8 pies. Or six stamps of 1 annas and one of 8 pies. Or 12 stamps of ½ annas with one of 8 pies. However, given the number of stamps involved vis-à-vis size of covers, such franking is hard to find.

Shortage Hits

On 12 June 1866, the Director General of the Post Office of India sent an urgent letter to the Secretary to the Government of India, then at the Indian summer capital of Shimla, high up in the mountains, appraising him on the shortage of 2 annas stamps (Figure 2). While the 8 pies stamp was the most important cog in making up the 6 annas 8 pies rate, the 2 annas stamp was not far behind.

Replying by telegram on 16 June, the Secretary authorised the Board of Revenue at Calcutta to overprint the word ‘POSTAGE’ across the 6 annas foreign bill stamp (Figure 3) as a temporary measure.

This stamp was meant to be issued only in the Presidency towns of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, which faced the greatest shortages.

Of course, what was needed was a more lasting solution. That is, a new stamp.

Issue of a New Stamp

Some months earlier, the Indian Post Office had requested that a stamp of value 6 annas 8 pies be printed.

On 11 May 1866, the Director General of the India Store Department at Westminster in London wrote to the firm which was involved in printing Indian stamps – the storied De La Rue. The letter stated:

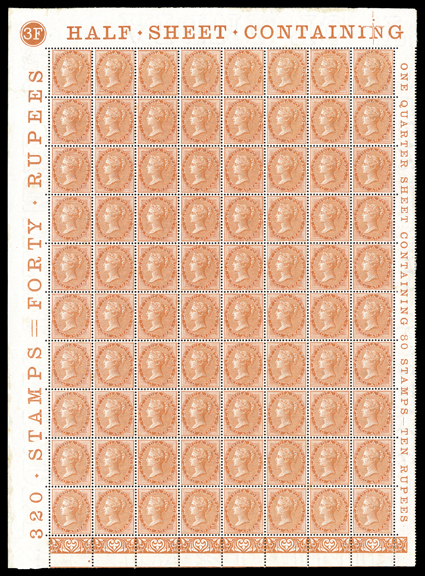

A demand having been received from India for 5,000 Sheets (320 Labels) of Postage Stamps of a new value viz., six annas and eight pies, I have to request you that you will submit a design for the same at your earliest convenience. It is requested in the correspondence from India that these Stamps should be markedly different in share from any now in use in India, as it is intended that they should be used for Postage between India and this Country.

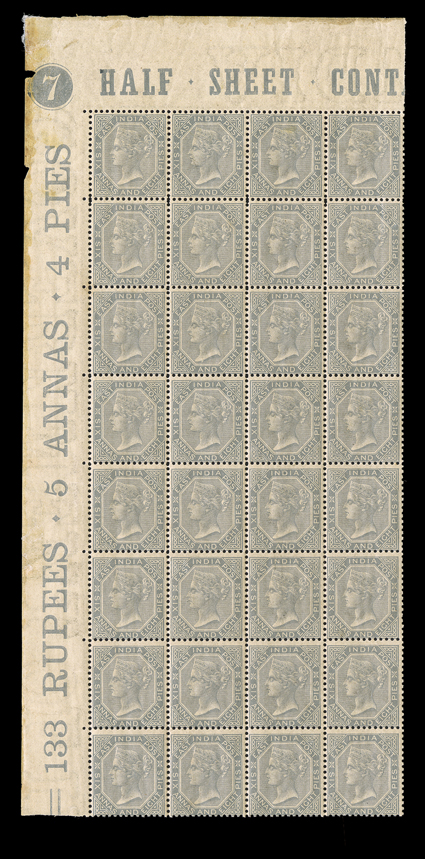

De La Rue submitted the design on 15 May. To ensure that the stamps were ‘markedly different’, the Queen’s head was placed inside an octagonal frame (Figure 4); the stamps then current had an oval frame (an example can been seen in Figure 2).

Upon approval of their estimates, De La Rue invoiced the delivery of the first batch of 2,500 sheets (800,000 stamps) on 6 October and of the second batch of 2,564 sheets (820,480) on 17 October 1866. Unfortunately, it is not known how many sheets of this particular denomination were printed in all; surely many millions.6

These stamps reached India in a few months time. On 23 March 1867, W. Cornell, the Superintendent of Stamps, issued a notice (published in Calcutta Gazette of 27 March):

A supply of six annas eight pie postage labels in one Stamp has arrived.

Treasury Officers whose stock of 8 pie labels is exhausted are at liberty to indent for a supply of the new postage Stamps according to estimated requirements7

Single Franking

Letters to GB with a single stamp of 6 annas 8 pies are not scarce but are not common either. Especially on civilian mails.8 This is because, within a year of their issue, the rate via Marseilles was increased to 8 annas 8 pies, with effect from 1 April 1868.

Of course, letters to GB after that date could still use the 6 annas 8 pies stamp, but only in combination with other stamps.9 The one exception was Officers’ Letters.10

In this section, we will cover single usage of the stamp on civilian and Officer’s Letters to GB.

Civilian Letters

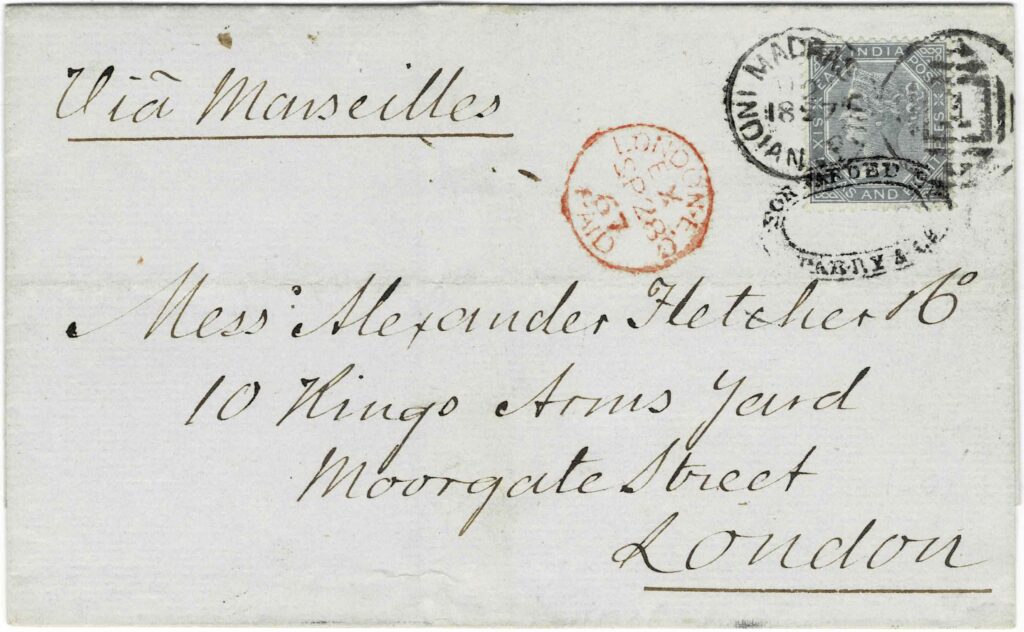

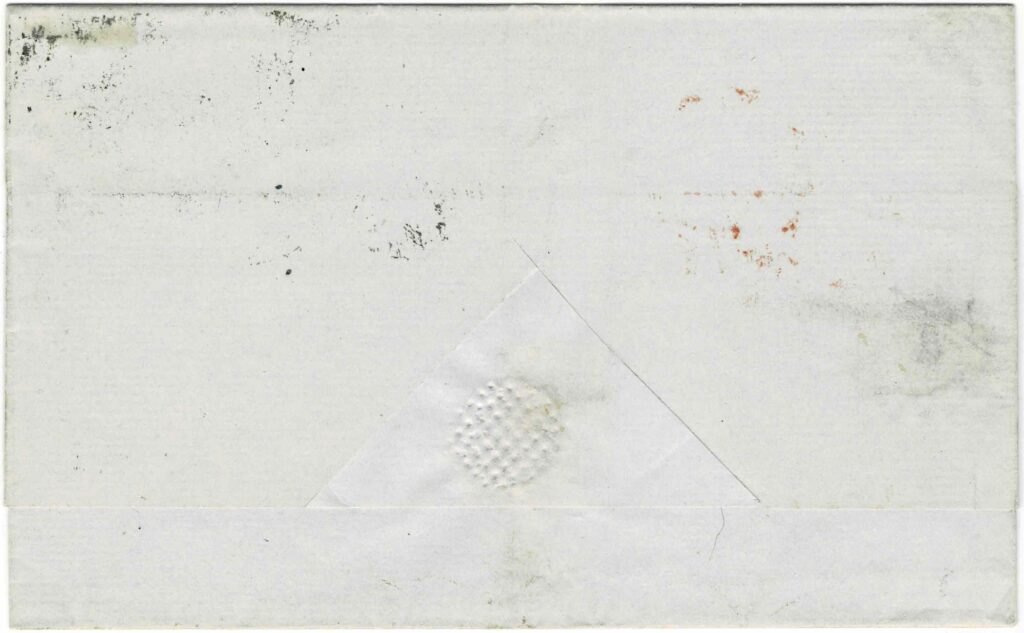

An example of a civilian letter is illustrated as Figure 5. The recipient’s docketing notes that it was posted on 24 August 1867 by the Madras based merchant, Parry & Co. and addressed to Alexander Fletcher & Co. in London.

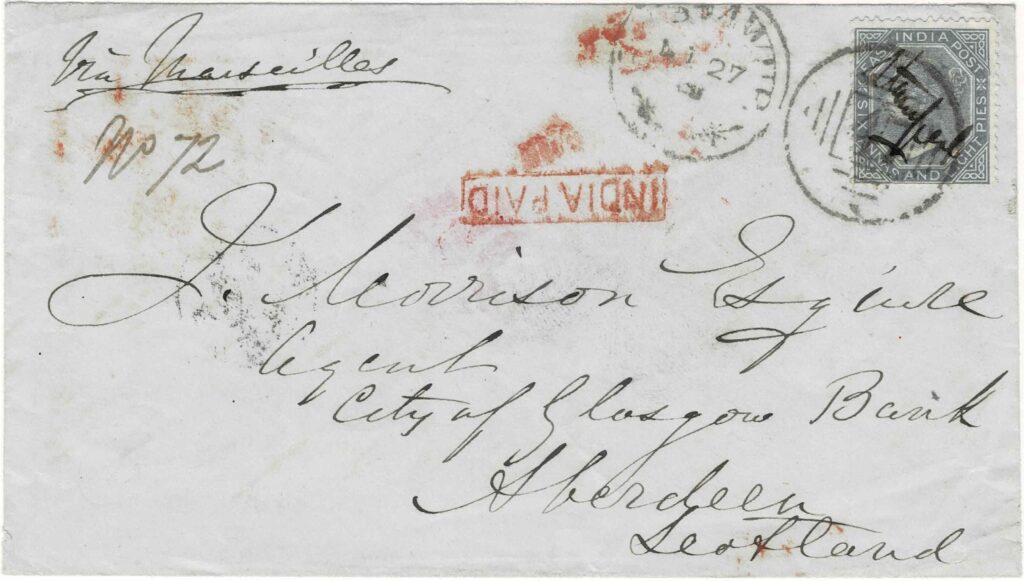

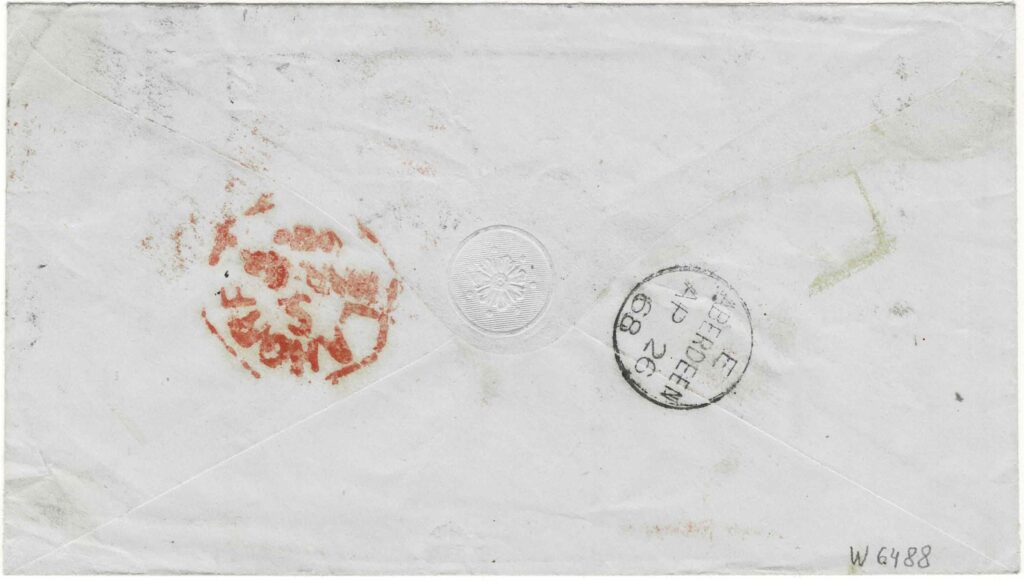

Another letter but from the final month in which the 6 annas 8 pie rate held good, i.e. March 1868, is shown as Figure 6. Posted on 27 March 1868, it was sent from the north-west frontier town of Peshawur to Aberdeen.

Officers’ Letters

From 1 January 1868 to 31 December 1869, the British government allowed its Army Officers to send and receive letters to and from GB at a concessionary rate of postage.

Until 1 April 1868, the civilian and Officers’ rates were the same. From that day, the civilian rate from India to GB via Marseilles increased to 8 annas 8 pies while the Officers’ rate remained at 6 annas 8 pies (until the end of 1869). I have written a detailed article on this subject and the interested reader is directed to it for more information.

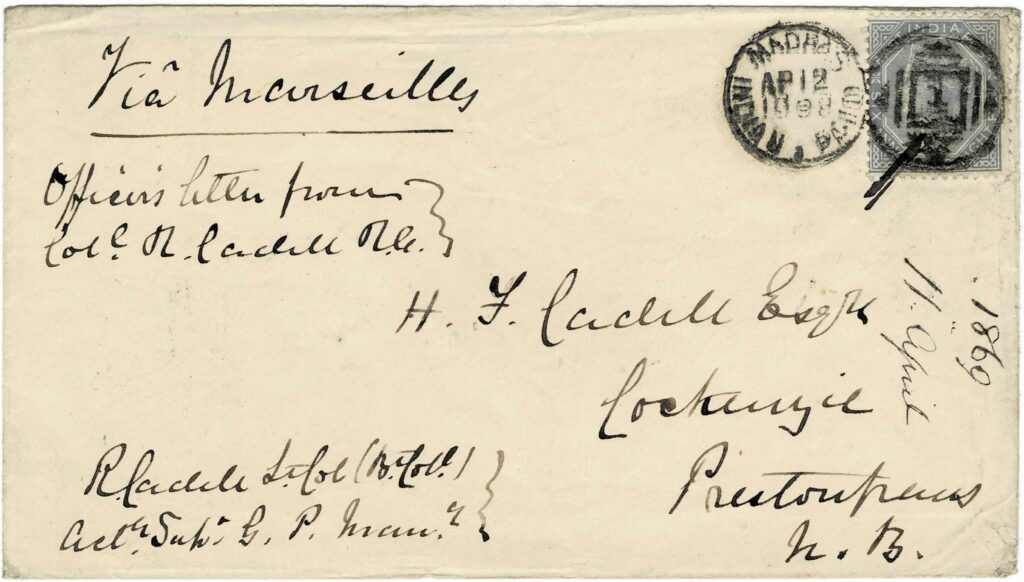

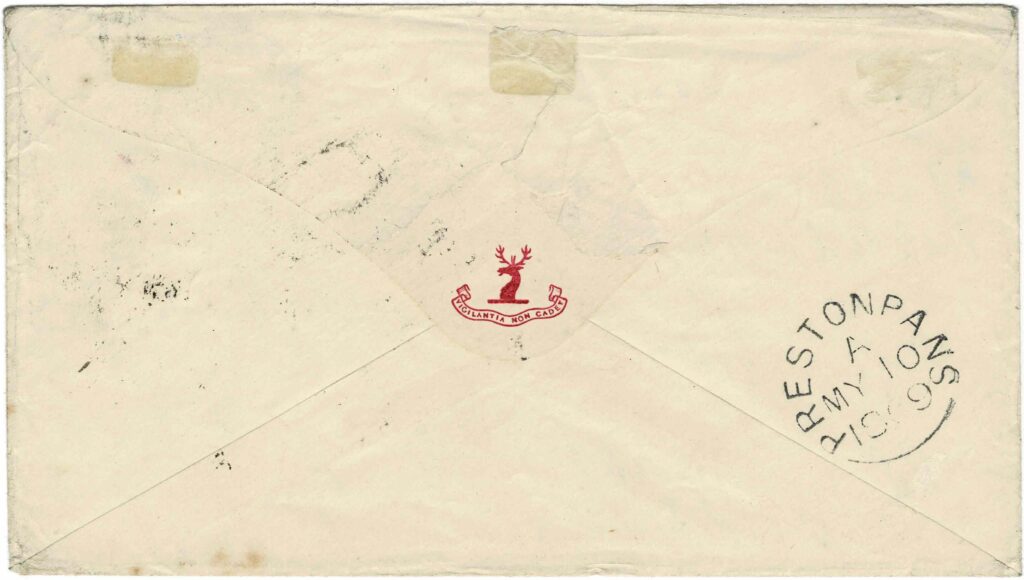

An Officers’ Letter bearing a single franking of the 6 annas 8 pies stamp is illustrated in Figure 7. The writer was one Lieutenant-Colonel (later General Sir) Robert F. Cadell (rhymes with ‘paddle’!) at the Madras Ordnance Commissariat Department. It was posted on 12 April 1869 from Madras and was addressed to his father at Cockenzie House near Prestonpans in Scotland.

From March 1868, all mails to the west sent on P&O steamers had to be taken to Bombay and sent out from that port only. They could no longer be carried by steamers from either Calcutta or Madras. Hence, the routing of the letter in Figure 5 (shipped out of Madras) is different to this.

Withdrawal and Destruction

In a letter dated 14 March 1874, the Director General appraised the Secretary to the Government (emphasis mine):

…It would be useless, however, to send to this country any more six annas eight pies labels. This stamp is now obsolete, having been obtained at a time when the value marked on it represented the postage chargeable on a half ounce letter from India to the United Kingdom via Marseilles. The route having been since abandoned, and the rates of postage altered, the stamp is now useless, and the stock in England must be sacrificed. The extent of this stock is stated to be 2,323 sheets…

Number of 6a. 8p. labels (not sheets) sold in the year 1872-3, 26,707

Stock in hand in India on 1-10-73, 6a. 8p. labels, 3,664,541

Stock in India both in Treasuries and Superintendent of Stamps stock will last: 6a. 8p. labels, 137 years and 3 months

The reserve stock in England will last: 6a. 8p. label, 27 years 10 months

So, enough stock for about 165 years existed! The Government of India must have realised the futility of keeping this stamp in stock, and subsequently sanctioned its abolition.11

The Director General wrote to the Superintendent of Stamps in Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay requesting them to cease selling the stamp from 1 April 1874.

Further, based on instructions received from the Governor-General, the Director General later instructed the Superintendents to destroy the whole stock retaining only half a dozen sheets as specimens. He also said that the stock should be destroyed in their presence; this was obviously to ensure that no pilferage took place.

The Superintendents reported back. At Calcutta, 6,245 sheets and 131 labels were destroyed. 3,179 sheets and 272 labels were destroyed in Madras. And 1,715 sheets and 260 labels were burnt in Bombay.12 This sums to total of 3,565,143 stamps not including the reserve stock of 743,360 held in England.

References

Easton, John. The De La Rue History of British & Foreign Postage Stamps. Faber and Faber, 1958.

Hausburg, L[eslie]. L[eopold]. R[udolph]., C[harles]. Stewart-Wilson, and C[harles]. S[tanhope]. F[oster]. Crofton. The Postage and Telegraph Stamps of British India. Stanley Gibbons, Ltd., 1907.

Moubray, Jane, and Michael Moubray. British Letter Mail to Overseas Destinations 1840 to UPU. 2nd ed. Royal Philatelic Society, 2017.

Kirk, R[eginald]. “The Mediterranean Sea Post Office.” In The British Sea Post Offices in the East. Vol. 4. 4 vols. British Maritime Postal History, edited by Edward B[axby]. Proud, 9-130. Heathfield, East Sussex: Proud-Bailey Co. Ltd., 2003

Tilleard, J[ames]. A[lexander]. Notes on the De La Rue Series of the Adhesive Postage and Telegraph Stamps of India. The Philatelic Society, London, 1896.

Notes

- The rate from GB to India had already been modified to 10d (=6a8p) with effect from 1 June 1863. ↩︎

- To those unfamiliar with Indian currency, 12 pies comprised 1 anna and 16 annas comprised 1 rupee. At this time, 1 anna was equal to 1½ British pence. ↩︎

- The 1 penny was to compensate the Indian Post Office for its costs incurred in carrying letters internally within the country i.e. for inland postage. ↩︎

- Of the 5 pence, 1 penny was British inland postage and the balance 4 pence was sea postage. The latter arose since the British Post Office contracted with steamship companies to carry mails and they were liable to pay them a fixed amount every year. ↩︎

- I use the word ‘strangely’ since the volume of India-GB mails was enormous and most mails were sent via the quicker Marseilles route rather than the slower Southampton one. Was it bureaucratic apathy or was it that the authorities expected yet another change in rates soon? ↩︎

- In his fantastic book, John Easton says that “The quantities of Indian postage stamps printed against the annual requisitions are so large that nothing could be gained by attempting to tabulate them.” ↩︎

- The initial supply of the stamp must have been small. Hence, only those treasuries, who had exhaused the 8 pies stamp, which was the most important in making up the rate, were to order for them. ↩︎

- Both personal as well as commercial correspondence would constitute ‘civilian mails’. ↩︎

- The Marseilles route was itself abandoned in October 1870 on account of the Franco-Prussian War. ↩︎

- Another exception is letters sent to certain countries in the late 1860s and early 1870s which cost 6 annas 8 pies. For instance, this was the rate to France for a couple of years effective 14 April 1871. However, in this article, we are looking at mails to GB only. ↩︎

- Tilleard (p.8) notes that a second plate of this stamp was registered by De La Rue on 1 December 1869. Hausburg (p.29) mentions there were three plates: ‘7’, ‘7A’, and ‘7B’, with the first being registered on 11 September 1866. It is strange why the additional plates were made given that the rate changed in April 1868. Did the bureaucracy take the eye off the ball and just forgot to stop the printing of these stamps? ↩︎

- Only Bombay reported that the stamps were destroyed by burning. While it is not known how Calcutta and Madras got rid of them, they are also likely to have burnt them. ↩︎